- Consecration

- Challenges in the Diocese

- Financial problems

- Mponda’s

- Meeting Jane and getting engaged

- Ecclesia

- Chaplaincy and Diocese

- Staff list March 1962

- Ordinands

- Early days

- Travelling

- South West Tanganyika

- Karonga

- Mzuzu and Likoma Island

- Canon John Kingsnorth and Jane to Likoma

- Birth of Chilema Lay Training Centre

- Matope

- The 1962 Synod

- Wedding

- Diocesan Standing Committee

- Preparations for America

- Departure

- Athens

- Rome

- World Council of Churches

Quite out of the blue I received a letter from the Archbishop of Canterbury in January 1961 asking me if I would allow my name to go forward for election as Bishop of Nyasaland.

I did not know the first thing about Nyasaland except a 60-year old bit of family history – Ernest Crouch, my uncle, had been a UMCA missionary who, amongst other things, built the Chauncy Maples steamer there in 1901. There is more about them both in the Appendix.)

I needed to ask someone whose opinion I could trust. I phoned Anthony and Mags Barker, doctors at the Charles Johnson Memorial mission hospital at Nqutu in Zululand, to tell them I needed their advice about something. After hearing my news, they said they would pray about it and tell me in the morning. In their bedroom, Anthony turned to Mags and said, “Thank God for that. I thought he might be calling to tell us he had developed VD (venereal disease)!” In the morning they told me I should go.

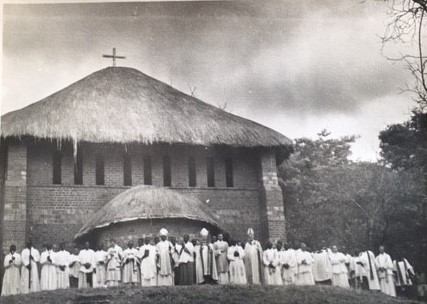

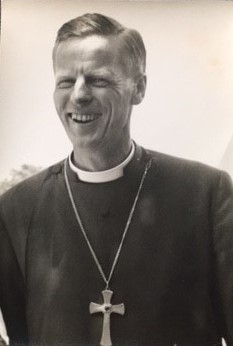

Consecration

Before leaving Swaziland, I became aware that there had been controversy about my appointment as Bishop of Nyasaland. The struggle for independence and state of emergency were in full swing. There had been agreement that a white bishop was needed. Apart from a handful of white UMCA (Universities Mission to Central Africa) missionaries, hardly any African clergy in the diocese had more than primary education, followed perhaps by vernacular training as a teacher and certainly none had experience of finance. But there had been a strong feeling that if a priest from South Africa was made bishop, he should have at least a whiff of Trevor Huddleston’s anger at apartheid. Luckily, it helped that I could describe myself as Australian, having been to school there and all my close family still living there.

Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, with whom I had paired up on the Zululand Diocesan Standing Committee as a two-man opposition, had promised he would write to Orton Chirwa, the most outstanding figure in Dr Banda’s newly formed cabinet, to certify my lack of respectability. I was therefore relieved to find Orton representing Dr Banda at my consecration, at the Church of the Ascension, Likwenu. This beautiful thatched church, aptly named as it was high up on the slopes of the mountain, was sadly destroyed by a bush fire in 1965. Orton, the brilliant and brave Attorney General, subsequently joined the opposition to Dr Banda and while in Zambia was seized by a Malawian police task force and later died in prison in Malawi.

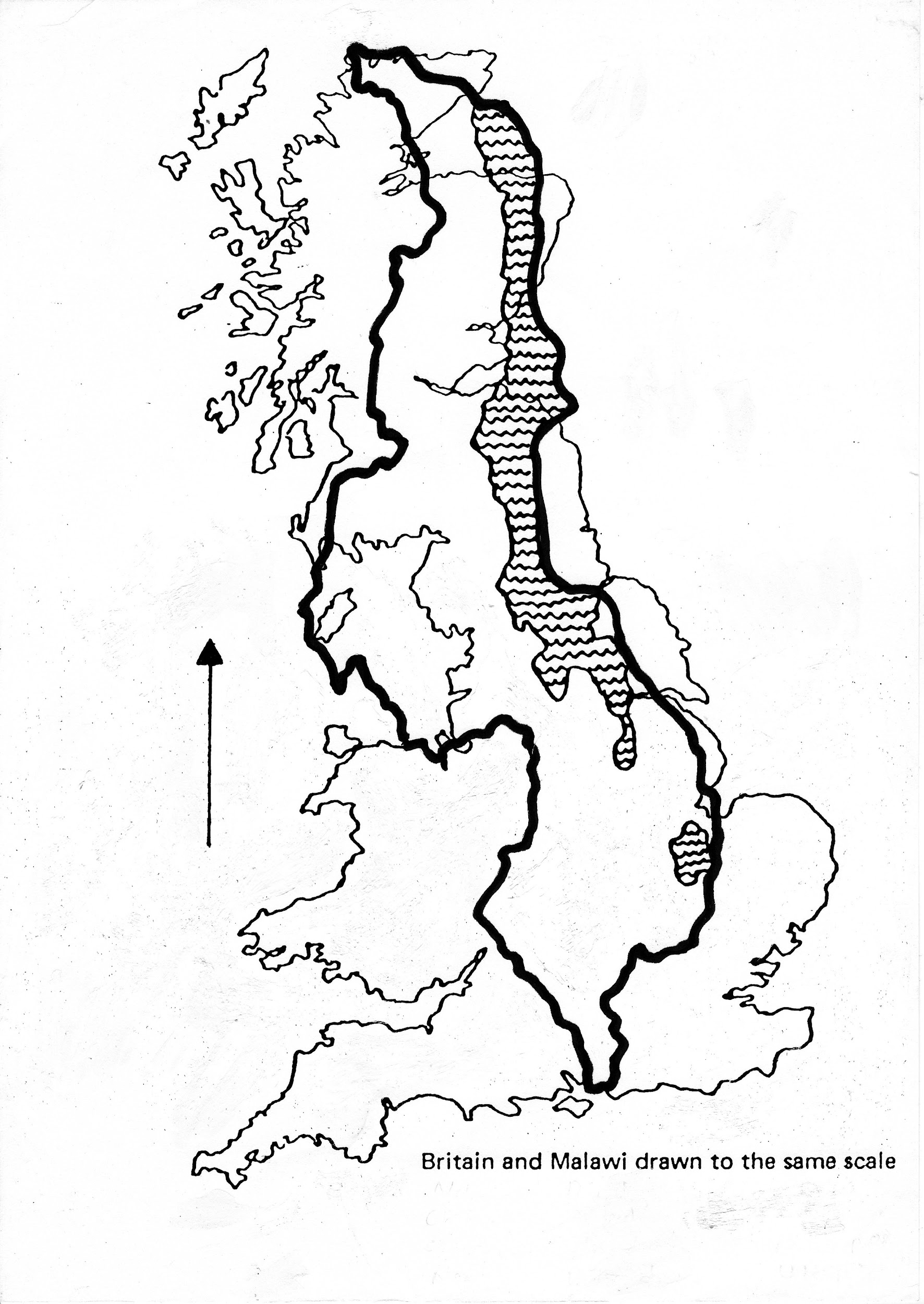

It was 1961. Past violence, present poverty and future uncertainty, were all in the air. During the State of Emergency, declared during the struggle for independence from the hated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, a number of people had been killed and many imprisoned, including Dr Banda in Gwelo prison in what was then Southern Rhodesia. There were high hopes for the future of this beautiful country, the size of England, then with a population of 3 million, but still much to be agreed before it became independent. (At its independence in 1964, the United Nations listed the new country of Malawi as the poorest in the world).

St Andrew’s Day 30th November 1961 at Mkuli – Malosa

At my consecration on St Andrew’s Day 1961, 30 November, The Archbishop of Central Africa presided, assisted by Bishop Cecil Alderson of Mashonaland, Bishop Obadiah Kariuki of Kenya and Bishop Tom Savage of Zululand. Tom Savage preached and passed on the few words that Jesus spoke in his own Aramaic language:

Abba – Father. You, Donald, can only be a father-in-God if your whole life is one of loving dependence on God the Father.

Ephrata – Be opened. Your task is to open the ears of the deaf – those who do not know Christ and the faithful that they may hear more clearly.

Talitha cumi – Little girl, arise. Expect new life to come to the church through your ministry.

Eloi, eloi. My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Your hands are to be signed with the cross. Accept the agony of bringing people to God, and in that sign go out to conquer.

Also present at the consecration was Canon Petro Kilekwa. Petro had been captured as a slave in Eastern Zambia as a young boy in the 1870s. He was marched nearly a thousand miles to Zanzibar, sold in the market there and taken in an Arab dhow to the Persian Gulf.

I felt about 3 inches high as I gave God’s blessing to the huge crowd outside the church, wielding the great diocesan ivory and silver crozier which contains part of the wooden staff wielded by Bishop Charles Mackenzie, who died of malaria and enteritis on the banks of the Shire River nine months after entering Nyasaland in 1861. The ivory had been presented as a peace-offering by a Yao chief after the murder of one of the early lay missionaries on the eastern lakeshore.

After the service, Dr David Stevenson, the diocesan doctor, famous for playing his bagpipes before dawn each morning on the Malindi lakeshore, called me aside. He said he looked forward to continuing to serve in the diocese but wanted to warn me that if war were to break out between Scotland and England, he would have to leave without notice to fight for Scotland .

Challenges in the Diocese

The first year in the diocese was heavy and I was not sure that I would survive. The twenty-three African clergy earned the equivalent of five pounds a month, hardly any of them had a bicycle that worked and their housing was dreadful. Their average age was around 60. We were allowed two places every two years at the provincial theological college in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) where students came from the four countries in the Anglican Province of Central Africa – Bechuanaland (Botswana), Southern and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Nyasaland. This would just allow us to replace the clergy who were retiring. Growth was out of the question.

When the Chauncy Maples was sold in 1957 and Likoma Island became virtually unreachable, the headquarters of the diocese was moved to Mponda’s (Chief Mponda’s place) on the edge of the Shire River at the southern end of the lake. This was 90 miles from the nearest sizeable town. In the wet season the road was flooded for days at a time, the post was erratic, there was no telephone and few visitors. If the church was to play any significant part in the new Malawi, it had to be closer to the centre of things.

Financial problems

In the post soon after my arrival was a letter from our bank manager. “Would I kindly refrain from signing any further cheques?” Our overdraft limit was £12,000 and we were now £20,000 in the red. That would represent perhaps £100,000 at today’s values. I asked the missionary treasurer for a balance sheet. He produced a statement showing we had a deficit of £3,000 for the past year and said that my predecessor had never asked for a balance-sheet. I drew a veil over further conversations.

In April, I wrote to my brother Felix, a paediatrician in Brisbane.

“In the diocese we are boiling up for a frightful financial row. We borrowed an auditor from Northern Rhodesia diocese who says there is around £10,000 missing and unaccounted for in the books. He doesn’t think it could be the treasurer’s fault ‘because he is such a nice man’ but he did say that every fact had to be prized out as with a corkscrew. Anyway, there seems to be enough evidence to give him the push which will be a great relief.” |

|---|

For seven days a non-stop meeting went on at Mponda’s – teachers, medical assistants, business people, black and white, trying to find some way of making the financial wheels of the diocese go round. Amongst other things it recommended we move the headquarters of the diocese to Malosa / Likwenu where we already had nearly a square mile of land.’

Likwenu had been an old tobacco farm of about three-quarters of a square mile. High on the list was to move the headquarters from Mponda’s to Likwenu/Malosa. It was in a largely Muslim area within 17 miles of Zomba, then the seat of government, and on the main road to the central and northern provinces (as they were then called). It already had the embryonic Malosa Secondary School (named after the 6,000 foot mountain ridge behind it), a small primary school, a leprosarium with about 100 patients, a church at the top of the hill, appropriately named the Church of the Ascension, and a small clinic, built above the school in the hope that mosquitoes would not find it. Mosquitoes were not deterred but patients were.

Mponda’s

Mponda’s was my home during 1962. It is a very large traditional village and the headquarters of the most powerful Yao Chief in the country. The apostrophe is an important reminder that the area belongs to Chief Mponda. At Mponda’s you are in no doubt that you are in the heart of Africa. On any night you would hear the barking of innumerable dogs, drumming for Muslim dances, hyenas as the treble, human voices and hippos as the deep bass.

In 1960, Chief Mponda had boycotted the visit of Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury, seeing him as a puppet of the hated Federal Government of Nyasaland, Northern and Southern Rhodesia.

A colourful place but hardly a suitable centre for a diocese roughly the size of England. It had no telephone. The nearest was in Fort Johnston, later renamed Mangochi, four miles away. When the road was under water, we could get no post. Zomba, the government capital, was 75 miles to the south and Blantyre, the main commercial centre, another 42 miles further on. Bishop Frank Thorne had left me a car which only kept going through the creative ingenuity of its wonderful driver, Robert Malidadi. The missionary nurses and priests visited their health centres and parishes by hitch-hiking on one of the few vehicles that used the road.

I wrote to my mother in Australia a few days after arriving at Mponda’s:

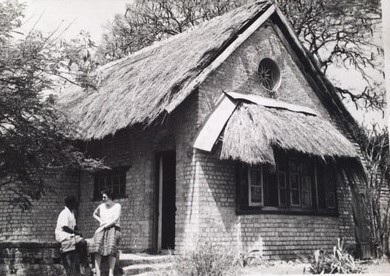

The flamboyant trees are all covered in red flowers. The mission is in the middle of the largest Muslim village in the country. Fortunately Chief Mponda consented to see me. As a keen member of the Malawi Congress Party, in its fight for independence, he refused to meet the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, three years ago because in his sermon he had commended the British Government’s policy of linking Nyasaland, Northern and Southern Rhodesia in a Central Africa Federation. The mission consists of a very lovely church in the middle, with the mezane (a Swahili word meaning mess and common room) and for each missionary a small thatched two-roomed house. Mine is the same but newer and in better condition. There is a big and flourishing primary school with Justus Kishindo as its excellent headmaster and a small maternity hospital that sees up to 400 outpatients a day. Joan Knowles is in charge of the hospital and is sister to Jonathan Knowles, who was with me at Mirfield and was killed at Dunkirk. On the other side of the Lake is Malindi mission, 15 miles away. To get there you go through Mponda’s village to Fort Johnston and there you wait for up to two hours, eventually crossing the 200 yard wide Shire River on an antique hand-pulled ferry, powered by a team of Yao men who sing hauntingly. Archdeacon Habil Chipembere is in charge there, father to Henry Chipembere, who invited Dr Banda to come back to Nyasaland to break the Federation and eventually to head its new independent government. Henry was imprisoned with many others by the Federal Government – I hope to visit him soon in Zomba prison. At Malindi there is St Michael’s Teacher Training College, a large primary school, a church designed as a small version of the cathedral on Likoma Island, a very busy hospital and the all important workshop on the lakeshore that used to service the Chauncy Maples and other boats. Now, through the gifted, pipe-smoking Francis Bell, the workshop provides an invaluable service to the various institutions and local villagers by mending and making anything mechanical. Francis has trained many mechanics who have become highly regarded throughout the country. Most buildings date from the 1920s and most of them leak! |

|---|

At Mponda’s, the ever loyal and encouraging Ron Tovey, at 35 the only young missionary priest in the diocese, knocked at my door one morning. Rain was steadily dripping through the thatched roof onto my desk, which I had covered with old newspapers, leaving only the typewriter exposed. “Let me show you something to cheer you up,” he said, leading me to Christine Moss’s house. She was away on a hitch-hiking visit to health centres. Ron pushed open the door of her house and opened the cupboard where her few dresses hung. Everyone was soaked and the rainwater dripped through them onto the mud floor. It was a good way of stopping my self-pity.

This was the first time I had worked with UMCA missionaries and I developed considerable admiration for them. Committed to being celibate, those who became engaged were asked to leave. Sixty of the first one hundred and fifty died from blackwater fever. They lived a frugal life, although even that was far more comfortable than those amongst whom they lived. There was a common purse to cover every day living and £30 a year with which to buy clothes and go on holiday.

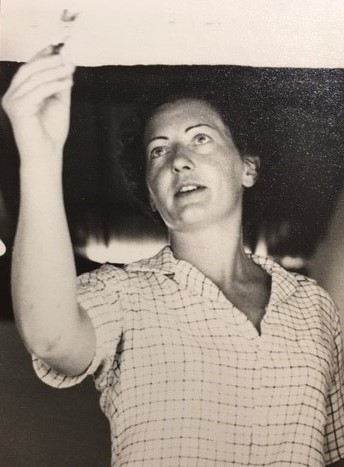

Meeting Jane and getting engaged

Jane and I became engaged on the slopes of Mulanje Mountain in Easter Week 1962. I had gone there to take Easter services. I had been working quite hard and felt I needed a day off so I wrote to the church warden of the little expatriate congregation at Mulanje called Mel Crofton. His wife Brigid was Jane’s twin sister. I later wrote to Mel and Brigid to confirm that I was coming and asked if it would be too much of a bore if I stayed on for a day and climbed their mountain. It is a magnificent mountain 10,000 foot high, with 3,000 foot vertical rock faces. Its plateau covers 100 square miles with birds and trees not found anywhere else in the world. At its base are rolling green tea estates.

Brigid opened my letter and is reported to have said to her sister Jane who happened to be staying there, “The bishop wants to spend an extra night here – you’ll have to entertain him!” After I left, Jane said to Brigid, “I hope the entertainment was adequate!”

On 27 April 1962 I wrote to my mother:

Thanks for wishing me a happy Easter. Before I tell you just how happy, please get three of your anti-dilatant drugs and suck them for five minutes … right? We’re getting married on Michaelmas Day. I’m too happy to write about this coherently but am more certain of the rightness of it than anything I have ever done. Her name is Jane Riddle, at present teaching in the St Andrew’s Prep School in Blantyre, born and brought up in East Ogwell in Devon, educated at a school run by the CJGS sisters (Companions of Jesus the Good Shepherd), taught in Stepney, came to Nyasaland three years ago, where her twin sister Brigid is married to a young Assistant District Commissioner, Mel Crofton. They are at present stationed at Mulanje, whereby hangs the tale. We first met when she arrived at Mponda’s with a car full of paint and Coloured Sea Rangers and started to paint out the whole mezane – a frightful job which involved spending a week up in the rafters – which were actually the slipway of the Chauncy Maples laid down by uncle Ernest – cleaning out the accumulated bat-dirt, cobwebs and lamp-oil grime of half a century. When I was in Blantyre on Maundy Thursday, she poked her head round the door, where the Rector and I were having a serious discussion about finance, to ask if I would like to help her photograph a beaked snake, a rare variety that a professional snake-catcher had found. When I saw her also taking a portrait of a boomslang (a very venomous type of tree-snake) from about 6” with a close-up lens (even the snake-catcher was getting worried!) I noted that she had that touch of recklessness that anybody taking me on as a proposition would need. It was quite by chance that my hostess at Mulanje was Brigid. I had picked that church out of a number where I could have gone for Easter. As it happens to be in the shadow of the finest mountain in Nyasaland, I thought I might stay on an extra day or so to climb it. On the Monday, we all had a wonderful picnic in Mozambique and on the Tuesday, Jane took me to climb Mulanje, the toughest day’s climb I have done for a long time – in alternate sun, rain, mist, more sun and finally dark. The next day we toured tea-estates, ending up with a film-show by a planter from Darjeeling. By the time we parted, I think we must have been engaged. It seems that we are likely to meet about three times before the wedding at Michaelmas, as I am hardly going to be at home at all and Jane is tied to the school. Our marriage will probably rock some of the UMCA staff a little, though not seriously, as she is well known by many of them. She is one of the very few Europeans who is completely at home with Africans, who call her by her Christian name without embarrassment – something you rarely meet. She has many accomplishments – officially a secondary school music teacher with PT and religious knowledge, enjoys small boat sailing and photography, does typing and shorthand, drives a car fast and well, is a running repairs mechanic, plays the organ, says her prayers, has a tremendous sense of vocation and an equally robust sense of humour, very calm and sure on the surface but rates about 99 on whatever scale it is that starts with frigidity at 0. One of Jane’s children, home from school, rushed into her mother full of excitement: Miss Riddle’s getting married. Who to? The Pope. Don’t be silly, the Pope doesn’t get married. Well, the Bishop, it’s the same thing. Is this enough for one letter? |

|---|

Breaking the news of our engagement to the UMCA missionaries at Mponda’s was a problem. One of them remained totally silent. Part of the mythology was that my predecessor, Frank Thorne, had been so overcome by the engagement while on leave of two serving missionaries, that he had left the room and was physically ill. But generally they were accepting and those I most respected, such as Archdeacon Christopher Lacey and Fr Ron Tovey, were clearly delighted.

A few days later I had a letter from Bishop Frank, then in Tanganyika, asking, “Are you a Jane (Austen) fan, like me? Would you please put my copy of Pride and Prejudice into the post.” He also asked about Jane Riddle, “She’s far too nice to be a spinster.” I felt the Lord had delivered him into my hands and posted the book the same day, with a note saying, “I am a Jane fan, but not in the way I think you meant. We have just announced our engagement and hope to be married in Michaelmas.” Frank responded at once with a delightful letter saying, “If I can come to terms with this and even be enthusiastic, I am sure that younger members of UMCA will do so even more quickly”.

Ecclesia

The diocese had other problems; how to communicate with clergy and laity in a country the size of England but with only one railway line in the far north where there was no Anglican work. A country with almost no all-weather roads, a skeleton bus system and a trunk telephone line which on the Nkhotakota lakeshore at least consisted of one single strand of fencing wire. Our answer was to launch Ecclesia. Ecclesia was a monthly 8-page magazine consisting of two sheets of foolscap size paper folded. It sold for one penny (0.5p in today’s money) and the annual subscription was 15p, to cover paper, envelope and stamp. It came out in two editions, English and Nyanja/Chewa. With rare exceptions appeared every month for 17 years.

The first editorial made the point that the missionaries of today are all of us:

‘The diocese is one. Whether our birth-places were in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) or Britain, in Tanganyika (Tanzania) or Australia or Nyasaland, we are all involved in mission. Those of us who come from other countries – as do most of our clergy, African and European – we come as your servants for Christ’s sake’.

Chaplaincy and Diocese

The five ‘white’ congregations – Blantyre, Limbe, Zomba, Mulanje and Thyolo – were not diocesan parishes but part of something known as the ‘European Chaplaincy’. This had its own structures and finances and never met the African church except at a brief annual synod. So Ecclesia announced a joint meeting of the Diocesan Standing Committee and Chaplaincy Fund representatives to be held on 4 May 1962 to decide on ‘many urgent matters.’

It was not an easy meeting. The ‘Winds of Change’ announced by the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, acknowledging the number of countries in Africa becoming independent, were only a gentle breeze in Nyasaland. It had always been a protectorate where few expatriates were allowed to buy land. It was not a colony like Kenya and the two Rhodesias, where expatriates were allowed to own land.

This had ceased to mean much in the Central African Federation, with Roy Welensky as Prime Minister of the Federation calling the shots. Even in the tiny capital of Zomba, where most of the inhabitants were European and African civil servants, the Club was ‘Whites only.’ Consequently, the Governor, Sir Glyn Jones, refused to enter it. Feelings about independence were even stronger in the tea estates of Mulanje and Thyolo.

There was, however, one highly respected tea-planter, Arthur Westrop. He had a background in Sri Lanka and in Scouting and had built All Saints Church in Thyolo. With the passion of an Old Testament prophet, he supported the merging of the Chaplaincy and the Diocese. When he sat down, the two became one without a single dissentient. It was agreed unanimously that henceforth the Chaplaincy churches were fully part of the Diocese.

Staff list March 1962

DIOCESE OF NYASALAND

STAFF LIST MARCH 1962

Bishop Donald Arden

Vicar General Christopher Lacey

Nkhotakota Archdeaconry Archdeacon: Guy Carleton

Parish Priest-in-charge Assistant Priest

Nkhotakota Oswsald Chisa Yohana Kapeta

Kayoyo Bernard Mbiza

Charundu Bartolomayo Msonthi Francis Nkongojo

Madanjala Cyprian Liwewe

Chia John Mwassi

Mlala Krispo Machili Jerome Bai (at Bua)

Shire Highlands Archdeaconry Archdeacon: Christopher Lacey

Likwenu – Malosa John Rashidi Frank Mkata

Christ the King, Soche Mattiya Mseka

St Paul’s Blantyre Edward Hardman John Parslow

Holy Innocents, Limbe & ???? Chichiri with;

St Andrew’s, Mulanje; All Saints, Thyolo; St George’s, Zomba

Matope Paul Lundu Barnaba Chipanda

Shire Archdeaconry Archdeacon: Habil Chipembere

Malindi Habil Chipembere Joseph Chikokota

Mponda’s Ron Tovey Martin Malasa

Samama Augustine Chande

Nkope Hill Michael Zingani Dunstan Chizito

Likoma Archdeaconry Archdeacon and Dean: Gerald Hadow

Jameson Mwenda Nathan Mtaya

George Ambali

Ordinands at St John’s Seminary, Lusaka

Nathaniel Aipa Benson Msonthi

Lloyd Chikoko Edward Nanganga

George Mchakama Peter Sauli (Deacon)

George Msakwiza

Medical Department

Likoma Hospital (St Peter’s) R.H.Mumford, Gladys Snell

Malindi Hospital (St Martin’s) David Stevenson, John Chandiamba

Nkhotakota Hosp (St Anne’s) Beatrice Anderson

Mponda’s Hospital Joan Knowles, Christine Moss, Smythies Merikebu

Nkope Hill Health Centre Geoffrey Chioko

Likwenu Hospital Richard Kapala

Likwenu Leprosarium Bill and Muriel Walter

College and Schools

St Michael’s T T College Wilfred Stringer

Malosa Secondary School Hilda Evans

Nkhotakota Hill primary schools Steere Kaphambe

Southern Province primary schs Justus Kishindo

Likoma primary schools Alban Chilalika

Various

Mothers’ Union Margaret Woodley

Diocesan Office, Mponda’s William Towers, Edwin Kaposah

Printing Office, Likoma Swithun Noakes and staff

Engineering Dept, Malindi Francis Bell and staff

Nkhkotakota Works/training Arthur Rawlings

Malosa Works Norman Holland

Ordinands

We were in desperate need of younger clergy. Of the 23 African clergy serving this 500 mile long country, most were over 50. A much welcome letter from Bishop Tom Savage, from whose diocese I had come, provided support in this area. He told us that all the Lent offerings of Zululand-and-Swaziland would be sent to us as a gift. On the strength of this, we were able to send five young men for priest training instead of the two for whom we had budgeted.

Early days

Exploring the diocese and learning its rich history, was the next task. The first missionaries to arrive in Nyasaland came in response to David Livingstone’s plea for Christians to come and stop the ravages of the slave trade. Bishop Mackenzie and his companions arrived in 1860. Many died of malaria and the survivors withdrew. Twenty-two years later, in 1880, two UMCA priests arrived. William Percival Johnson and Charles Janson walked eight-hundred miles from Zanzibar and six weeks later were the first Anglicans to see the lake. Charles Janson died a few days later Fr Johnson soon lost the sight of one eye and 80% vision from the other. With 20% vision in just one eye, he continued to work around the Lake for the next forty-six years. During this time he translated the Bible into Chinyanja by the dim light of a hurricane lamp. His name is in the Calendar of Saints in Central and Southern Africa.

Click here for a lovely booklet written about William Percical Johnson in 1931 – in .pdf format

Likoma Island being a dry, rocky island. (five miles by one and a half miles), lies two miles from Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) coast to the east. It was chosen as the headquarters of the Diocese because of its safe harbour, its insulation from raids by slave traders and its comparative freedom from malaria. It was the headquarters of the Diocese until the Chauncy Maples steamer was sold in 1957.

As befits the headquarters of a diocese, between 1902-1905, there arose on the island a magnificent cathedral only slightly smaller than Winchester Cathedral, complete with cloisters, library and Chapter House.

See history of cathedral in the Appendix

Chauncy Maples, or the CM as she was universally known, used to do a monthly round of lakeshore mission stations in Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique), Nyasaland (now Malawi) and German East Africa (now Tanzania). It was not until 1906 that a party led by Canon Petro Kilekwa opened the first church at Kayoyo in the Ntchisi hills, midway between the Nkhotakota lakeshore and Lilongwe.

Travelling

The first months in the diocese were times of almost continuous travelling and my mind was a blur of new scenes and new faces, with many standing out vividly: the Muslim village headman in blue robes kneeling for Confirmation, after facing the opposition of his family and the surrender of his chieftainship. Blessing Christians kneeling in the sand from the bow of ‘Boatie Paul’ as one arrived at lakeshore villages. Being taken with pride by a village congregation to see the huge kiln of bricks they had burnt for their new church. The double baptism of an African and a white baby, where the godmothers on each side happened to be wearing identical dresses. Evensong on the lawn of a government headquarters after being driven out of the building by swarming nkungu flies – tiny flies that erupt in their millions from the bottom of the lake. Little things perhaps, but they all make up the joy and life of the Church in Africa, which went into the new era full of vigour, however inadequately equipped.

South West Tanganyika

Five days after our engagement, I left Mponda’s on a six and a half week ulendo (journey) to attend the consecration and enthronement of John Poole-Hughes as Bishop of South West Tanganyika – part of the Diocese of Nyasaland until 1953 – and to explore the Northern Region of Malawi. For this, I took ‘Boatie Paul’ from Likoma Island. She was an iron flat-bottomed barge designed for work on the placid canals of Holland and would ride the often large waves of Lake Malawi by thudding down into the valley of the waves with a shuddering smack. There was a lively discussion among the crew about the weather prospects, of which I understood almost nothing. I was acutely conscious that only 16 years earlier the newly built Vipya, a large passenger steamer, had turned turtle a few miles out of Nkhata Bay and three hundred and thirty-nine of her passengers and crew drowned. I was grateful that the consensus of the crew of Paul was that we would make it to Mbamba Bay in Tanganyika.

Karonga

From Tanganyika, I headed back to Likoma Island and from there to Karonga in the far north on M.V. Ilala, the only passenger ship on the Lake, and efficiently run by the Nyasaland Railways. I wrote to my brother Mike from Karonga:

“I got up at four this morning as Ilala sailed up to the top of the Lake – a lovely pearl-grey morning with the Nyika plateaus to the west looming out from the mists and the first light of dawn coming over the Tanganyika escarpment to the east. As the sun rose, it picked out great pillars of nkhung flies – a curious phenomenon on the Lake. The eggs hatch underwater on the lakebed and you can see the spiralling great columns, going several hundred feet into the air – they stand out while like steam coming off the water. “At six, Ilala cut off her engines opposite Karonga, and one of the lifeboats was lowered to take me to the beach, where I was left feeling very small and lonely until Tony Mott, the District Commissioner, arrived a few minutes later. From then on, I was passed on from one centre to another, and in each there was a group, most of government servants and their families, some British, some African, clearly delighted at the chance of sharing evensong or a eucharist – this is a region where I had been told the Anglican church hardly existed. It was something that at that time you could only dream about in Pretoria or even Swaziland. |

|---|

The north is the Scotland of Malawi – beautiful, mountainous, thinly populated, mainly by Tumbuka speakers. In 1962, it was mainly Presbyterian, the fruits of the work of Dr Robert Lawes and others from the Church of Scotland. Lawes held doctorates in medicine, theology and philosophy and worked from Livingstonia for thirty-three years.

In contrast, there was no Anglican priest on the northern mainland in 1962. There were small and lively inter-racial congregations, usually of civil servants, meeting in government buildings or private houses. These were visited occasionally by priests from Likoma Island. Here I met for the first time Alec Rubadiri, the first African Assistant District Commissioner (ADC), an outstanding man.

Mzuzu and Likoma Island

There was panic when I reached Mzuzu, now the capital of the Northern Region. A telegram had been received from one of the lay missionaries on Likoma Island: “For God’s sake send police reinforcements.” A government launch was laid on to take Canon Jameson Mwenda and myself, together with 20 armed police, to the Island where Chikanga, a witch-finder had set up business. It turned out to be mostly panic. Some women had been hauled off to be tested for witchcraft by Chikanga and many Christians had broken church law by bowing to public opinion and seeking an all-clear from Chikanga, without that all-clear their neighbours would have regarded them as witches.

I then returned to Nkhata Bay on Paul and after more visits took Ilala back to Monkey Bay, where we arrived 40 minutes ahead of time. And there to meet me was Jane on the wharf! We swam and talked and swam and talked. What we didn’t realise when swimming out to the anchored Chauncy Maples at Monkey Bay, was that people watching from the shore were taking bets on whether we would return. The day before they had been watching a large crocodile sunning itself on the rocks near the CM! Back at Mponda’s there were some 250 letters of good wishes on our engagement to be acknowledged. I took the easy way and sent a circular letter, churned out on the ancient hand-turned duplicator. The letter ended:

In this lovely country – I had heard about her Lake, but why did nobody tell me about her mountains? It is easy to be bemused by the beauty and the pulsing life, and to forget her real problems. How to provide food for the most densely populated territory in Africa; how to tackle malaria and TB; how to find work for the tens of thousands of young men that stand idle round every village market-place; how to provide schools for the half million children still without education – these, in this desperately poor land, are problems to crack the head of any economist. |

|---|

Canon John Kingsnorth and Jane to Likoma

The far-sighted John Kingsnorth was coming to explore the Nyasaland church. He had worked for many years in rural Zambia and had just taken over as General Secretary of UMCA in London. He also had the prophetic touch and was awake to the new reformation happening in Rome and with the World Council of Churches in Geneva. He needed to see the diocese at first hand and so did Jane – she would be spending four months talking about it in the States. So they went off together to Nkhotakota, Likoma Island, Nkhata Bay and Mzuzu.

Jane would have had a good reception on Likoma. The UMCA practised strict housing segregation. Male missionaries had their houses on the west side of the square, women on the east. A church elder had said to me after our engagement was announced, “We’re glad you’re being open about it. We always thought they did but it’s good to be honest!”

Jane and I met up again at a Student Christian Movement conference at Chongoni.

Birth of Chilema Lay Training Centre

I attended an SCO (Student Christian Organisation) conference at Chongoni, near Nkhoma, the headquarters of the Central Region Synod of the CCAP (Church of Central Africa Presbyterian) The Presbyterians, together with the Roman Catholics, were by far the largest churches in the country.

The CCAP problem was the same as ours: how to staff a rapidly growing church from a non-elastic seminary. Their solution was training the laity and they were planning a small centre: one staff member and 20 students. I said that was odd – we were considering an identical plan. Where was their centre to be? The answer – Domasi, just 8 miles from our new proposed headquarters at Malosa. It was crazy!

What God was calling us to do became clear. We quickly consulted our own church committees on the proposal to join together and establish an ecumenical centre on land at Malosa on independent land cut off from the diocesan headquarters and placed under the control of ecumenical trustees. Both churches agreed at once. The centre would be called Chilema Ecumenical Training and Conference Centre, named after the small stream that flows through the land. We were later joined by the Catholic Church, until some years later they developed their own catechetical centre. A fourth partner was the Churches of Christ, a body dedicated to ecumenism.

At this time, Jane and I were just about to leave on a four-month fundraising tour in England and the United States – we were asked to re-route ourselves via Geneva and to secure the backing of the World Council of Churches for the proposed new centre. Today, Chilema Ecumenical Training and Conference Centre is known throughout the country. The Churches of Christ and Roman Catholics later became members of the Board.

Matope

In June, I visited the parish of Matope for the first time (a parish in Malawi can comprise anything up to twenty or more widely scattered congregations). The name means ‘mud’ and is at the point where the Shire River, after flowing broadly and gently out of the Lake for 70 miles, hits its first cataract. This mass of water then tumbles down from the Lake level of 1,500ft to the Zambezi, a fraction above sea level.

It was here, in 1884, that Archdeacon William Percival Johnson was stranded by the dry seasonal fall of the river level. By this time he was blind in one eye and had 20% vision in the other. Being stuck in the mud at Matope for a few months was for him an opportunity. In three months, he baptised the first Christians and built the first Anglican church away from the lakeshore.

After two confirmations in the parish on the Saturday, I ended up at a village called Malawi. This was before the whole country adopted the name. Malawi is thought to refer to the glinting of the rising sun on the waves of the lake. The children had been waiting for me from around noon and by this time it was quite dark. Thinking the church was a hundred yards away, I took a couple by the hand and the whole pack followed. The church turned out to be about a mile away. Anyway, it warmed me up on a chilly night!

The rest-hut was freshly smeared and looked damp and uninviting so I set up a camp-bed outside. I found it rather chilly so I got a couple of cassocks to put on top.The next day, I woke up in broad daylight in the middle of the village street in a bed decorated with a purple cassock and all the children standing around expectantly!

Another confirmation there and on to the old Matope mission station. The boat that served as a ferry was locked up and it took an hour to find the man with the key. We launched the boat to cross the wide river back to Matope but it turned out it had only one oar. That was not enough to stem the flow of the river and the rapids were unpleasantly close. So we man-handled ourselves up the reeds for half a mile then paddled furiously with the one oar to cross the river.

There was a wistful look about Matope at that time. It had a fine set of buildings, church, school, hospital, clergy house but the old bridge that had been nearby had been washed away and the new one built four miles lower down on the new main road. Most of the people had gone there also, the passing trade of hungry bus passengers being their main source of income.

The 1962 Synod

The Diocesan Synod had not met for three years and I called for one in August. This would be make or break time. Would we be able to catch up with the ‘winds of change’ blowing through Africa and the world – or would we die a slow death? I isolated myself for a week with Cecil and Maude Winnginton Ingram in Zomba to devise a new constitution for the diocese. Cecil’s father had been Bishop of London and Maude was an excellent typist and we all worked on it together.

The Diocese met for its fourth Synod in August at Malosa. The Bishop’s charge began with a tribute to the saintly, witty and tough Bishop Frank Thorne, whose 25 years of leadership had ended unhappily. The police, then controlled by the Federal government of Southern and Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, had shown him a list of people who, they said, were on the list to be murdered. Frank had quoted this in the Diocesan Chronicle, one of the world’s least known publications. The Chronicle was printed by the Likoma Press and had a circulation of perhaps 200 past and present UMCA missionaries. By some extraordinary chance, Frank’s comments came into the hands of a Daily Mail reporter. Frank had said he was himself a supporter of African independence and never dreamed that Dr Banda’s Malawi Congress Party would even think about political murder had he not been shown compelling evidence that very day. Next morning saw headlines in the London Daily Mail, ‘Bishop confirms murder plot’. Frank never forgave himself. Years later, when I saw him in London, not long before his death, he was saying over and over again, “How could I have been so stupid?”

The points I tried to make in my charge were:

The new age. The great feature of the new age in Africa is that power has passed from Christians to other Christians, not to atheists, as in France, or to Marxists, as in Russia.

An age of the laity. We need lay men and women who, like Stephen, are “full of faith and the Holy Spirit.” People are not to be judged by the colour of their skin, nor by the colour of their politics as in Germany or the Soviet bloc; nor by the size of their car as in the West. They are valued because women and men are the children of God.

Readiness for the new age. We could hardly be less ready. There were only twenty-three African clergy. The poverty of Nyasaland hinders our development. (It was listed by the United Nations as the poorest country in the world when it became independent in 1964). Government grants for schools and hospitals are a fraction of those in neighbouring countries with revenues from copper or from industry.

Our needs:

A nerve centre. Most of our work in the past was in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) and Tanganyika (Tanzania) . Ten years ago, the diocese was divided into three and the Chauncy Maples sold. Mponda’s is not a suitable centre for a diocese. The Bishop is out of touch, both with the government and his own diocese.

We have hesitated between Lilongwe and Malosa for the new centre but it is too early to move to Lilongwe. Perhaps that is where a suffragan bishop should be? Here at Malosa we already have a secondary school, a primary school, a hospital, a leprosarium and plenty of land for future development.

Adequate clergy. In 12 years from now there will be ten clergy that have not retired and the population will be a million larger. We have relied on our 300 teachers until now to take charge of out-station churches. We can no longer do this as they will be deployed by the government. Let us learn from the South West Tanganyika diocese. When they were divided from us ten years ago they had 14 priests; next year they will have forty.

We need to train clergy at three levels:

- At least a handful of graduates who will have to be trained in other countries.

- The majority of at least Junior Certificate standard, trained at St John’s seminary in Lusaka.

- A single group of ten or more older men for a shorter course, to tide us over the next 15 years.

Self-help. How can standards be raised and the number of clergy increased? There is only one answer: every parish must learn rapidly to support its own priest. At present, the total cost for all the clergy is £5,000 a year. Their parishes provide £250 of this.

A Diocesan Training Centre is needed to train older ordinands, full-time catechists and a new voluntary army of Readers. (As the letters ‘r’ and ‘l’ are often interchangeable in Chichewa, they have appropriately been known since as ‘Leaders’). Other openings for lay volunteers are as Youth Leaders, Sunday School teachers, Church councillors and Stewardship Campaigners. We all need to see our daily work as work for God.

Self-government. We need more than a Synod every two or three years. There must be organs empowered to take decisions between meetings. This is so urgent that I am presenting a new set of Draft Acts for experimental use until next Synod. These will give us a Diocesan Standing Committee (DSC) invested with the full powers of Synod, except for a very few vital areas. The DSC will have full authority in all matters of finance. The new Acts provide for elected councils in every parish. They give us our own trustees so that church property will be no longer held by trustees in London. They give us a Diocesan Secretary to share the burdens that threaten to overwhelm your Bishop and auditors to see that our finance is properly accounted for. These new Acts will help us to cut the apron-strings and grow into an adult church.

Money Our financial position is disastrous. No audited accounts have been published for seven years. During this time, we have spent between £25,000 and £30,000 more than our income. To help meet this gap we have been given an emergency grant of £15,000 by UMCA. A special grant of £10,000 made to each of the four UMCA dioceses to put buildings into working order has also been given to the bank manager to pay off part of the overdraft. But this does not help the future. We have got used to living at £6,000 a year above our income. You are all too familiar with the forced economies: selling the Chauncy Maples; closing St Andrew’s Theological College, the printing works on Likoma Island; the ordinands not sent for training; the closure of churches at Namwera; the leaking roofs…

There are four steps that we can and must take:

- Control our finances through the DSC.

- Decentralise: parishes and institutions must take their own steps to survive.

- Make new friends overseas. My wife and I propose to spend five months fundraising in the UK and USA. We ask for your prayers.

- We must learn to give. Our troubles would end tomorrow if every one of us, rich or poor, gave each month one day’s earnings – in cash, crops or fish.

One thing I know. This Diocese can find the resources to grow, human and financial. This is already happening in a diocese that until ten years ago was part of our own, equally rural, equally poor – South West Tanganyika. We have invited Mr John Nkoma, a lay member of their Finance Board, to this Synod to tell us how to do it. We look forward keenly to hearing what he has to say.

One Church. I quote from Bishop Stephen Bayne, the first Executive Officer of the worldwide Anglican Communion, “It is not enough that missions should grow into self-governing churches. They must grow into one self-governing Church.”

Our diocese was born in two separate places: on the eastern lakeshore where Archdeacon William Percival Johnson arrived, coming overland on foot from Zanzibar; and in the south, where the little overseas community had organised the Chaplaincy. We need one legal framework for both and we need the experience of both.

Equally urgent is the need to be at one with Christians of other traditions. We must be strong to bear witness against all the forces of the devil that divide us. I commend most earnestly the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity from January 25th, if possible with Christians of other traditions. I ask you to take any other steps which will lead us to our goal of unity in Christ. Let us pray to the Spirit:

Come Holy Spirit;

Come in gentleness as a dove

making us to be at one;

Blow within us as the wind,

filling us with new life;

Burn within us as fire,

setting us aflame with the love of God.

Wedding

Jane and I were married in St Andrew’s church, Mulanje on Michaelmas Day, 30th September 1962 from the home of her twin sister Brigid and her husband, Mel Crofton, who was Assistant District Commissioner. (We learned much later that St Andrew’s was not licensed for weddings under Nyasaland law and a special Act of the Malawi Parliament was passed to legitimise Bazil and Christopher. But legitimacy was the least of our worries.)

The dramatic backdrop to the wedding, out of the back garden of Brigid and Mel’s house, on the slopes of Mulanje Mountain, was a sheer wall of granite rises 5,000 feet to the Mulanje plateau, on which another more jagged range runs up to Sapitwa (The Place You Don’t Go To) at 10,000 feet.

The previous day, the Usuthu team from Swaziland – Jack Dobson, Peter Burtwell and Bernard Wrankmore – arrived in Bernard’s battered jeep. Bernard had driven from Cape Town, picking up the others on the way. They drove one thousand three hundred miles non-stop, taking it in turns to sleep and drive.

Guided by Brigid, everyone was involved with stuffing olives and preparing the wedding feast until after midnight. Habil Chipembere and Christopher Lacey – the two archdeacons in the Southern Province – took the service and a mixed choir from Malosa Secondary School and St Andrew’s Prep School led the singing, including a hymn that took us both back to our school days:

Breathe on us, Breath of God,

Till we are wholly thine,

Until this earthly part of us

Glows with thy fire divine.

Preparing food for the reception. From left to right, Bernard Wrankmore, Brigid Crofton, Peter Burtwell, Bette Riddle, Jack Cormack, Dorothy Riddle, Jane, Jack Dobson (facing camera).

Jane was a photographer’s dream in a glorious white dress made by Brigid. In the bright September sunshine, a brisk wind blew her veil around like a ship’s pennant, in front of the rolling green of tea bushes that surround the granite walls of Mulanje mountain.

When we came to make our getaway, the ancient Standard car which I had inherited from Frank Thorne was true to type and broke down after the first half-mile. We coaxed it back up the hill to Mel’s house where, while we thanked the prisoners from the local gaol for tidying up after the party, Bernard swapped his suit for overalls, adjusted something underneath, and so we made a second farewell. A mile down the road, a repeat performance – after which Mel offered us his Land Rover and, at the third attempt, we made the 180 miles to Namaso Bay and the cottage of a friend.

David Eccles, of the Fisheries Department, kindly lent us a small sailing dinghy and our fortnight was a glorious mosaic of the rare Pel’s fishing owl, listening to the haunting call of

the magnificent fish-eagles, grey louries, three types of kingfishers, two types of hornbills and a friendly one-legged wagtail, a couple of crocodiles on the rocks, and, out in the lake, a huge turtle, the only one we ever saw – and each other. It was the first time since our engagement we had both been in the same place for more than two days.

Back at Mponda’s we changed an ancient thatched house with some beautiful 1901 brickwork into a family house by putting two single iron beds together. Unfortunately the mattresses were a size larger and Jane fell out of her side in the middle of the night.

Diocesan Standing Committee

The first Diocesan Standing Committee – the new power-sharing organ set up by synod – was held in late October with nineteen clergy and lay members. It had eighty-seven items on its agenda and the minutes filled thirteen pages. It decided that:

- The move to Likwenu should happen, despite the cancelled grant. The new bishop’s house would be taken off the list (it was 1965 before it was built) but the office and houses for the Secretary and Treasurer would go ahead.

- The new office would have its own telephone.

- A layman, Frank Chithila – the Medical Assistant on Likoma Island – would represent the Diocese at the 1963 Toronto Anglican Congress – the last that has ever been held. In the event, Frank was unable to go and Clement Marama took his place.

- Professional auditors were appointed for the first time.

- A bilingual Eucharist – Nyanja and English on facing pages – would be published immediately

- A new ecumenical training centre would be established at Chilema.This would not only train. catechists, it would also enable laymen who had proved their worth as catechists or as voluntary helpers to be ordained as priests.

- Michael Blackwood, a solicitor in Blantyre, was appointed Chancellor and did sterling work for the next fifteen years.

- Justus Kishindo, the excellent headmaster at Mponda’s and Supervisor of Education on the Lakeshore, was appointed Diocesan Secretary.

I doubt if the diocese would have survived had Justus not made the decision to sacrifice his government pension as a teacher and come to work with the diocese. He was later joined by his friend, also a teacher, Maxwell Zingani, who made the same sacrifice and who became our Stewardship Adviser and Literature Secretary.

Quite apart from their own areas of responsibility, they would now and then make an appointment to see me in the evening and say – ever so gently – “Bishop, we are not sure you made the right decision when you said …” Invariably they were right and I changed course.

Preparations for America

A four month visit to the USA had been planned for some months. It was the only hope of finding the resources to pay off our many debts and to bring into reality even a fraction of the many hopes for the diocese.

At Malosa, the site for the new headquarters for the Diocese, there was a lot of land suitable for farming and building and steeper land where trees could be planted. Government had already taken back a small part and was threatening to take much more if it was not put to use to benefit the community. UMCA had offered £20,000 to enable the diocesan headquarters to be moved to Malosa, but on terms the diocese could not meet financially.

The only hope of a new beginning was to find help from America. I had no contact with the Episcopal Church of the USA, known as ECUSA, other than with a priest in Chicago called Dick Young, so I had gone ahead before our engagement and arranged with him a four month visit early in 1963. For a time it seemed as if Jane would be an abandoned wife within a few months of our promising to have and to hold each other, till death parted us. Then her family generously stepped in to make it possible for us to keep those vows and accompany me on the trip.

I had met Stephen Bayne at Provincial Synod in Lusaka, Zambia. He was an American bishop who had just been made the first Executive Secretary of the Anglican Communion. He was impressed by the needs and possibilities of Nyasaland and encouraged me to go ahead with plans for a visit, mentioning the possibility of companionship with the Diocese of Texas. This meant going a month earlier than planned. Texas was holding its diocesan convention in February; our plans had been to arrive in March. Stephen’s enthusiasm communicated itself to the Diocesan Standing Committee which generously gave me leave to be away for six months.

Much had to be squeezed into the next two months. Dick Young wanted lots of photos – we had none larger than 6”x4” and could not afford commercial enlargements. So the Swaziland enlarger, operated by a car battery, was called back into service. Each night, after supper with the mission staff in the mezane (eating place), we would set up the enlarger in our new bedroom. The danger point came at around 8.30pm when the missionaries would leave the mezane and head for their rooms, swinging paraffin Tilley pressure lamps. Every dish had to be hastily covered to protect them from light until people and lamps were safely in their rooms. Mosquitoes in the developer didn’t help either. Often the production of photographs would be accompanied by noises off from hippos grunting on the banks of the nearby Shire River. Eventually we reached the target of 50 8”x10” photographs. Many other dreams were reduced to a 5-year plan and I began to feel more confident about the forthcoming trip to the States.

The unexpected, good and bad, continued during the last few weeks before we left for our American odyssey. The £20,000 grant from the UMCA for the headquarters at Malosa was suddenly withdrawn – no reason given.

This was counter-balanced by a letter from Dunstan Choo, a fine Nyasaland priest whom I had known in Pretoria in the 1940s, when he was a priest in the northern Transvaal copper mines. His letter asked if he could return and work in Nyasaland. There he was provided with a car and, by South African standards, a modest salary. I thanked him and said I could offer only a push-bike and a salary one-tenth of what he was receiving. I received an immediate reply: this was a call from God and his intention was fixed, no matter what the salary, the transport or the housing. He came in due course and was the first priest ever to be based in the mainland area of northern Malawi. Later he became the first archdeacon of Northern Malawi, which, in 1990 grew into the Diocese of Northern Malawi.

Departure

As we left Blantyre in mid-December after a week with little sleep, a small team from Blantyre Synod of the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP), led by the Revd Jonathan Sangaya, came to the airport to see us off. I had earlier been asked to re-route ourselves via Geneva and to ask the World Council of Churches to support the building of what would be the first ecumenical institution Malawi had ever known. There could not have been a more encouraging send off as we left for Europe and the United States.

Athens

We took advantage of the free stop-overs on our flight to London and Athens was our first stop. I had been learning Greek for nine years in Australia, Leeds and Mirfield but had never had a chance of seeing Greece. We enjoyed plodding from ruin to ruin and seeping in the wonders of the highest culture the world has known. The oracle of Delphi had always fascinated me. It was the age when sharp-witted Athenian statesmen, historians and philosophers, generals and heads of state would still consult the oracle before making great decisions. How do spirit and mind interact? How do science and the humanities cross-fertilise children’s education? I asked the Oracle of Delphi, “How do you become a rounded human being in a world of specialists?” As usual the reply was oracular.

We visited Cape Sounion which was fittingly being battered by a winter storm as the sun set in a red glow. Jane and I were almost alone, imagining the women from Athens and Peiraios peering through the salt spray for a glimpse of Triremes returning from battle with the Spartans. Were they wives or widows? They would know today or tomorrow. On the bus returning to Athens there were only two young women beside ourselves. By one of those freak chances, both were from Queensland and one a doctor whom my brother Felix had taught.

Rome

It was our first time in Rome, again a bitter winter’s day. St Peter’s had its seating arranged for the Second Vatican Council which had begun its work in October (it ended in December 1965). We had little idea of what it would mean in the years that followed. Already, by calling together the Second Vatican Council, the 80 year old ‘caretaker’ Pope, John XXIII, had sparked off an internal reformation as significant, but more peaceful, than that launched by Martin Luther four hundred years earlier. Names previously unknown to me, such as the Swiss theologian, Hans Kung, were opening doors that could never again be shut. Little did I think that we were to follow him in Chicago.

We changed our route to London to include the stop-over to see the World Council of Churches in Geneva and a helpful airport official in Rome said, “Let me book your luggage through to Heathrow rather than Geneva and you won’t see it again.” How right they were! That was the last we saw of the case with all our plans and all our photos until it turned up, three weeks later, just before we left England for Chicago. An agonising wait.

World Council of Churches

The only day we could be in Geneva was a Saturday which fortunately then was still a working day. I discussed the proposals for the ecumenical lay training centre at Chilema with people in the Department of Laity, who gave it a very warm welcome. The meeting with the WCC went well as they very much wanted such centres to be ecumenical. Substantial funding followed this meeting. In due course, grants came which enabled Chilema to open its doors in 1964.

England welcomed us with a frozen Christmas beauty we’ve seldom seen before or since. The country was sparkling white in the sun when we landed at Heathrow and the snow was still virgin when we left for Chicago a month later. It was the first time I had seen England for 20 years – what a welcome! The airline had lost our luggage and we had no warm clothes. Mercifully Norman and Barbara Gilmore – now returned from Zululand and living in north London, took us in and clothed us until our suitcases eventually arrived. To have lost our clothes would have been inconvenient but to have lost all our photographs and slides, would have been disastrous.

Mel and Brigid Crofton, Jane’s sister and brother-in-law, together with their children Julian and Nicola, were on leave in England and we had the joy of sharing a white Christmas with them in their home county of Devon in the lovely village of Holne, on the edge of Dartmoor.