Petro Kilekwa – slaveboy to priest

Present at my consecration was Canon Petro Kilekwa. Petro had been captured as a slave in Eastern Zambia as a young boy in the 1870s, marched nearly a thousand miles to Zanzibar, sold in the market there and taken in an Arab dhow to the Persian Gulf. A British naval ship came alongside the dhow, released Petro and his friends, after which Petro became the Admiral’s Cabin Boy. Petro was eventually ordained and did wonderful work as a priest in Malawi. On a shelf in his thatched village house at Mtonda sat a Victorian travelling clock with the inscription To Petro, with grateful thanks from Admiral Benbow.

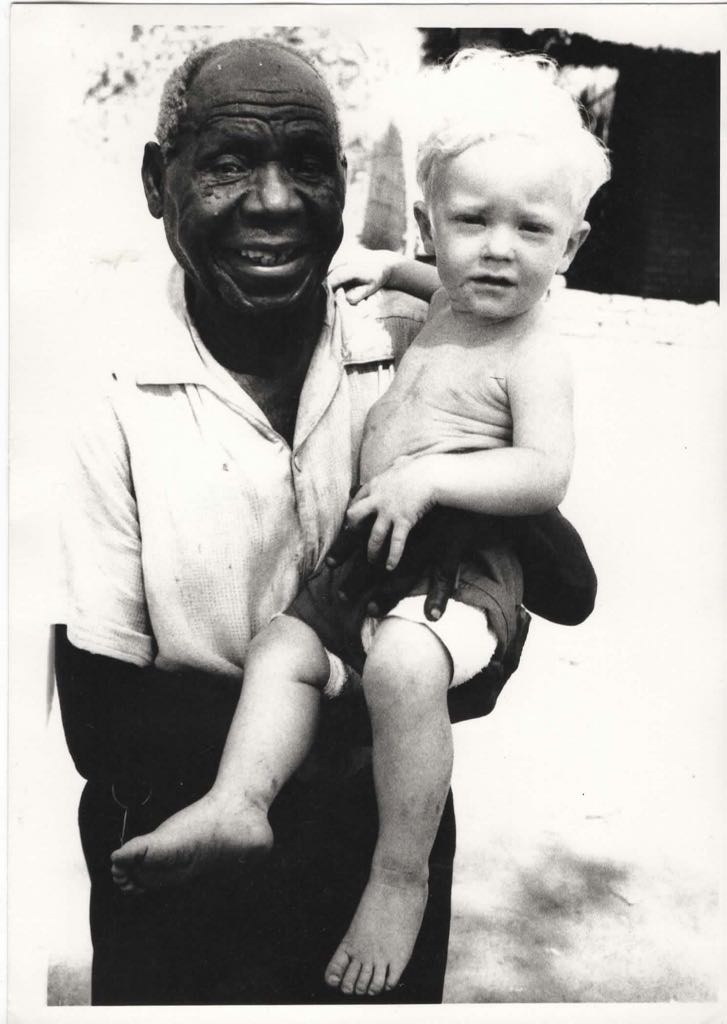

When Bazil was three months old, we took him to see Canon Petro Kilekwa, then aged 94 or 95. He was up a ladder re-thatching his house and came down to greet us. His story encapsulates something of the intertwined history of Islam, the Yao people among whom we lived and the focus of Anglican mission in Malawi. His story is taken from Slave Boy to Priest which he had written 30 years earlier.

|

|---|

Petro Kilekwa with Bazil – 1965 |

Petro must have been eleven or twelve when he was captured as a slave near Lake Bangweula in north-eastern Zambia. His mother tried to ransom him with three yards of calico but the ‘coastmen’ demanded eight. A yoke was fitted to his neck and they marched him away, alert to attacks by Angoni raiders from Zululand and lions. After walking some hundred and fifty miles they arrived at Samama on the western shore of Lake Malawi, just north of Mponda’s. There his Arab owner developed smallpox and called to Petro to lie close to him, saying, “If I die, we die together. If I live, we live together.” The next morning the Arab died, but Petro survived and was sold to Yao traders who dealt in slaves. A year later he was resold, marched 500 miles to the Indian Ocean coast at Yikindani, put on board an Arab dhow to sail to the Persian Gulf.

One morning there was panic. A small boat was coming towards them. The Arabs shouted, “Get below in the hold! These are bad men who eat black boys!” Petro and his friend leapt into the hold as the hatch-covers were put on and lay on the bottom of the boat, hardly daring to breathe. Eventually Petro and a friend were transferred to a man-of-war on anti-slavery patrol, HMS Osprey and were landed at Muscat in 1885. They sailed up the Euphrates to Basra and then to Bombay. Petro was then transferred to the flagship, HMS Bacchante. Petro became the punkah boy to Admiral Lord Charles Scott, pulling a rope that moved overhead curtains, making a light breeze. His companion, Mwambala, was only punkah boy to the captain, said Petro with a smile.

They sailed again to Bombay for Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887, then to Colombo, Aden, Madagascar and finally to Zanzibar. As the Baccante was heading for England, Petro and his friend were put into St Andrew’s College, Kiungani, built by the UMCA to help released slaves. He stayed there for six years, eventually training as a teacher. He returned to work in Nyasaland, arriving in 1899. As a teacher, he opened the first school at Ntchisi in 1907, and later came back there as deacon and priest. But most of his ministry was in Islamic areas at Nkhotakota and on the eastern and southern Lakeshore.

Petro was priest-in-charge of Nkope and Sani for eighteen years, 1930 – 1948, which included the whole forty mile stretch from Monkey Bay to Mponda’s where many of the people were Muslim.

Canon Petro retired to Mtonda, near Monkey Bay, building a house on a plot of land given to him by the Government in recognition of his fine work in Africa. He called the house Kiungani after the place in which he had spent so many years after being released by the slave-traders. Petro died in 1967.

Petro’s Wikipedia entry

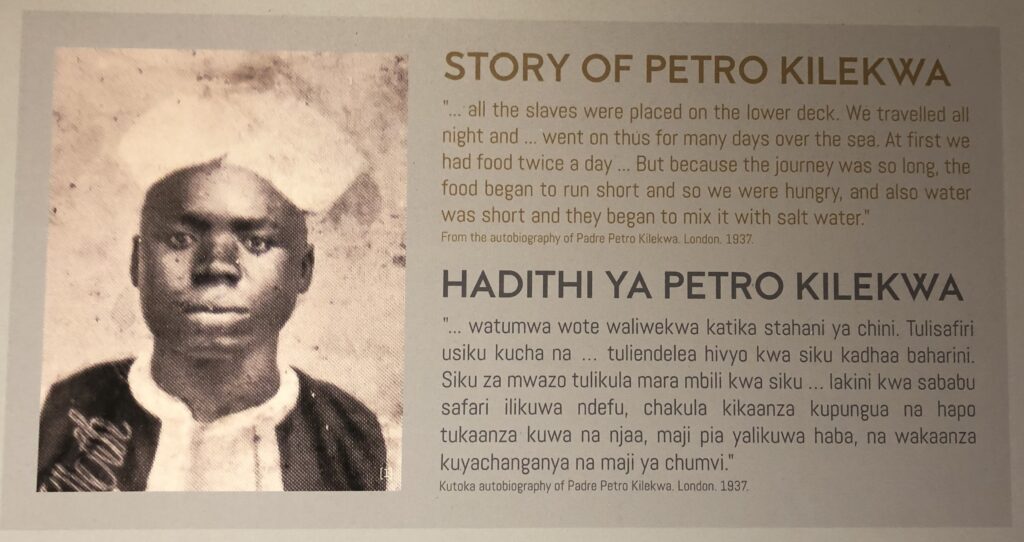

Editor: In 2019 Bazil came across this story of Petro Kilekwa in the Slavery museum in Zanzibar

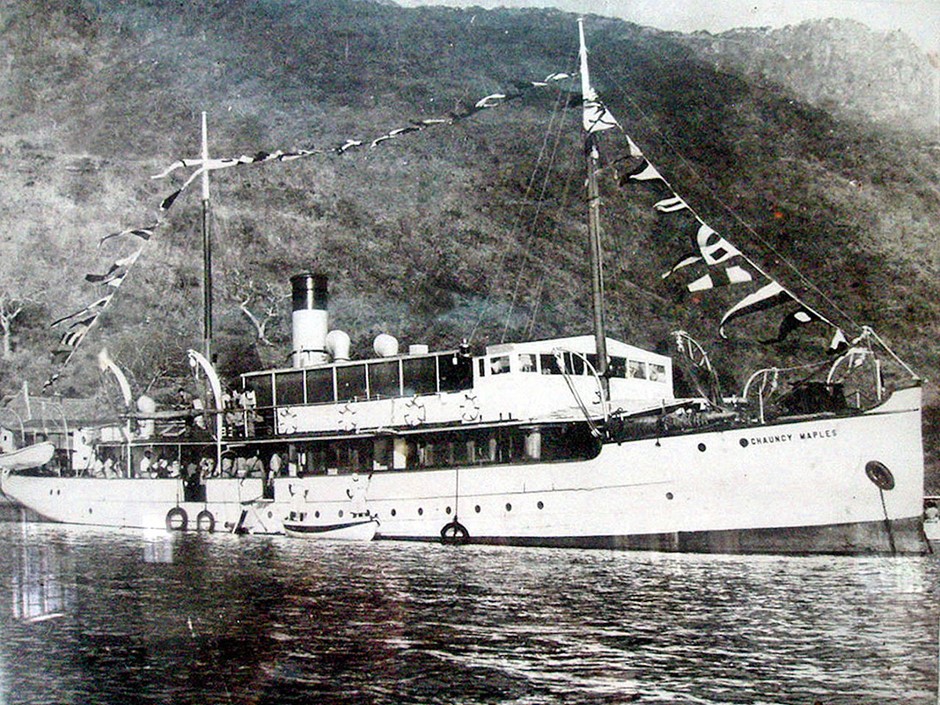

The SS Chauncey Maples and my Uncle Ernest

Lake Malawi is approximately the days of the year long and the weeks of the year wide and sits in the southern end of the great Rift Valley that stretches from the Red Sea to Zimbabwe. In the days before roads, travelling by boat around the lake was the obvious way for missionaries to do their work.

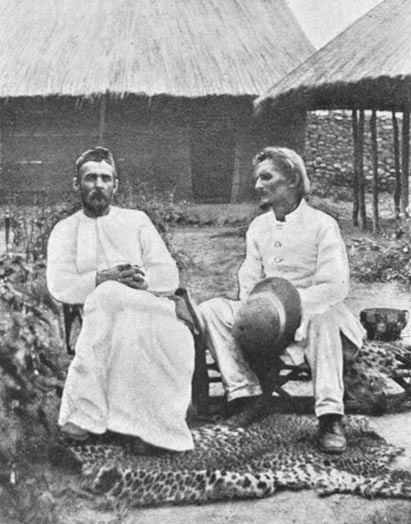

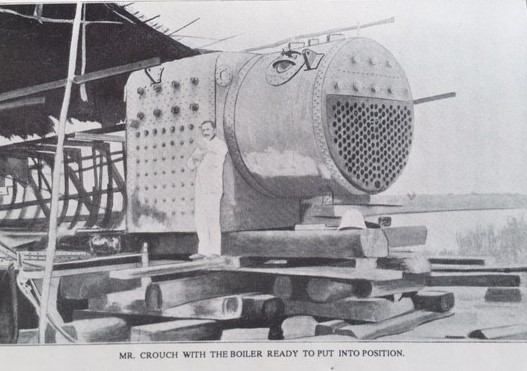

In 1890 my uncle, Ernest Crouch, joined the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) as a ship’s engineer. He first served on the Charles Janson a small steamer built fourteen years earlier. While working on the ‘Charles Janson‘, Uncle Ernest, was asked to prepare specifications for a new larger steamer. As well as supplying the lakeshore mission stations, ‘Chauncy Maples’ was to be a floating teacher-training and theological college. She was to be named after Bishop Chauncy Maples who had drowned on his way to his consecration in the cathedral on Likoma Island in 1895.

Uncle Ernest was sent to Scotland to order a ship to his specifications. She was ‘mocked-up’ on the Clyde, taken to pieces, each of her plates numbered and sent off to be galvanized. She was then packed into 3,500 crates, except for the huge boiler, which could not be taken to pieces. All these were sent by cargo steamer to Quelimane, the Indian Ocean port at the mouth of the Zambezi River. Then 400 miles up the Zambezi and Shire River into Nyasaland.

This southern end of Nyasaland, known as the Lower Shire, is 1,500 feet lower than Lake Nyasa and the Shire River cascades over a series of non-navigable rapids. The crates containing the ‘C.M.’ were converted into 4,500 head-loads to be carried through the bush to lake level. The boiler was dragged by 450 Angoni men on a carriage made out of cart-wheels. This they pulled 100 miles, climbing 1,500 feet singing and making the road as they went. When they reached Matope ‘the place of mud’, the Shire became navigable again. Eventually the whole lot arrived at Mponda’s, just where the river runs out of the Lake.

(Photo courtesy of Lady of the Lake)

To his horror Uncle Ernest discovered that in the process of galvanizing, all the numbers on the plates had been wiped out! Only he knew the pattern. At Mponda’s mission on the banks of the Shire, they cleared and levelled a one acre site and laid out the pieces. The next few months were spent on a steamer-sized jig-saw puzzle – “That plate belongs over there, that one’s part of the bridge …” I don’t know what the hippos who plodded out of the river each evening in search of food, thought of these strange inedible shapes.

The only mistake in Glasgow was not using galvanized rivets and that is the only reason why she failed her M.O.T. 95 years later. The plates are still as good as when they were assembled in 1900 but the rivets that held them together have rusted. She was one of the world’s longest serving steamers, working commercially on lake or sea.

The vision that the ‘C.M.’ would be a floating teacher-training and theological college did not work out as the students became sea-sick. But from 1901 to 1957 she steamed around the Lake paying monthly visits to missions and centres in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), Tanganyika (Tanzania) and Nyasaland (Malawi). For many years she provided the only link between these centres as there were no roads, carrying people, stores, medicines, produce, animals, chickens and anything else you think of.

Likoma Island was the headquarters of this large diocese extending into four countries – Tanganyika (Tanzania), Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland. After leaving UMCA in 1901, Uncle Ernest became chief engineer of Bristol docks and built the present dock gates.

The boiler on the ‘Chauncey Maples’ was fired by wood and in 1957 it became clear it was no longer practical to do this, so she was pensioned off. By that time she was probably one the world’s oldest ships still in active service.

The fact that she remained in good health for so long and especially during the 1939-45 World War, was largely due to a remarkable UMCA missionary, Francis Bell, who, for forty years in his workshop on the lakeshore at Malindi serviced the Chauncey Maples’, making a spare part if it was not possible to buy it. Francis was also in demand from local people for his skill in despatching marauding lions.

In 1967 the British government refitted her as a present to the Malawi government so that she could assist the M.V. ‘Ilala’ as a second passenger ship on the Lake. His Excellency the Life President of Malawi, Dr. H.Kamuzu Banda took part in the re-launching ceremony at Monkey Bay and I was asked to lead the prayers and to bless her in her new work. Uncle Ernest must have been smiling down on us all.

She continued to sail around the Lake until 1990 when the rivets holding the plates, which had not been galvanised, began rusting and made her unseaworthy.

A book entitled ‘The Lady of the Lake’ written by Vera Garland, a friend of ours who lived in Malawi, provides a fascinating account of the life of the CM. Vera was unaware that Ernest Crouch was my uncle.

There is some more history on wikipedia

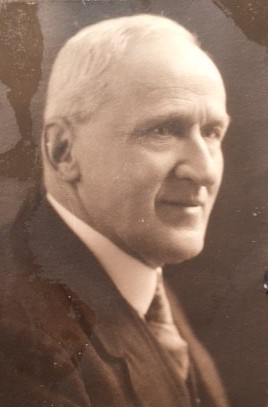

Archdeacon Christopher Lacey 1905-1968

I suspect the only reason Christopher had not been elected bishop was that he was chairing the three-person commission to whom the Elective Assembly had delegated the election when it had failed to secure a two-thirds majority.

There were no half measures about Christopher. He had intended to be an agriculturalist and was half way through his course when he decided to train for the priesthood instead. When he arrived in Nyasaland in 1937, he was posted to Likoma Island, in charge of the most isolated cathedral in the world.

A former parishioner on Likoma wrote: It was on Likoma that Fr Lacey got his nickname ‘Achirwa’. The clan name Chirwa was the commonest on the island. It was because of his friendship with many people on the island, together with his cheerful and friendly manner that people came to look on him as one of themselves and to call him ‘Achirwa’ – the ‘A’ being a friendly form of address.

The words that best describe Christopher are gaiety, simplicity, spontaneity. Life for him seemed to be full of surprises: he never quite understood why people should want to love him and give him things, like the new typewriter that came just at the end of his life. He was the epitome of UMCA at its best, firmly rooted in a magnificent tradition and in the gospel virtues of simplicity and singleness of mind and love.

You would never imagine there had been any price to pay. When we were living together at Mponda’s he could be found sitting at the side of the road waiting for one of the passing cars to give him a lift to a congregation fifty miles away. He gave the impression that he preferred to travel that way because it was more fun and you met new people. Christopher would say, “Did archdeacons in other places really have cars to do their visitations?”

Many of the good things that had begun to happen started from his visions. He played a large part in the founding of the Presbyterian/Anglican Lay Training Centre at Chilema and the discussions on unity with the Christian Council and Roman Catholic Church.

When he was transferred to be parish priest of Limbe and Archdeacon, it was – among other responsibilities – to be warden of a hostel for young men who had come to work in the city from places such as Likoma and Mponda’s that he knew so well. He was always concerned that people should see Christ the Redeemer as well as Christ the Judge.

It is symbolic that this last brief illness began at a service in the Presbyterian church in Blantyre and was aggravated when, against medical advice, he drove 62 miles to Malosa for discussions in preparation for a meeting of the Catholic-Anglican joint committee.

A wholly characteristic story I heard only after his death: how after his operation, with drainage tubes and drips going in all directions, he had turned to a visitor and said: “We must have a new verse in the Benedicite: all ye Pipes and Tubes, bless ye the Lord, praise him and magnify him for ever.” He was buried in the graveyard at Limbe.

In a letter to me in 1962 Christopher wrote: “It would be silly and wrong to stay on till one is old and decrepit. God saw to it that he never became either. It was wholly right that his Requiem Mass was that of Easter Day. For him, life was perpetually springtime and in his presence, we were constantly reborn.