(Renamed Eswatini in 2018)

The Usuthu Mission

Having said ‘Yes’ to Bishop Tom Savage I drove the two hundred and fifty miles from Pretoria to Swaziland in the new Bedford half-ton pick-up to begin my work as Director of the Usuthu Mission in September 1951. Apart from Wilmot Jali, the parish priest, his wife Rosina and the few labourers employed on the mission, I found the congregation at the Mission on strike. They had vowed never to enter the church again.

The Diocese of Zululand, based at Eshowe, three hundred miles away in Natal, was congratulating itself on its decision to keep only 120 acres for the mission and to sell the other 5,000 acres to the Swazi Nation at half the normal price. The nation was far from being grateful. The diocese was unaware that the land had been given free of charge to Jekeseni (Jackson, missionary at Usuthu in the 1890s) by Mbandzeni, the Paramount Chief and the father of Sobhuza II, who succeeded him in 1900 and remained Paramount Chief until the 1980s. They were saying, “Your neighbour’s wife has a new baby but she has no milk. You lend him a cow. Two years later, the baby is weaned. Does he then sell it back to you?” Everything depended on good relations between the Church and the Swazi nation.

I sent a telegram to the bishop saying “Please cancel sale or I will return to Pretoria.” He did so and I stayed. The strike was over.

The Usuthu Mission had responsibility for the work of the Anglican Church in half the country. Its centre was a small church in the Malkerns Valley built before World War I, a primary school and two new rondavels (round huts). One was to be our living quarters. The other, the bedroom. Later we built a small house. The Usuthu had been closed as a mission station in 1913 because of malaria and was an outstation of Bremersdorp, a town twelve miles and now called Manzini, the place of waters.

The Usuthu was to become the home of the Mirfield Old Students’ Mission to Swaziland for the next ten years. The first Old Student to serve was Anthony Molesworth who had been a curate at St Mary’s, Blyth, in Newcastle diocese. He was a great linguist and storyteller but not all his stories were printable. Others who joined later were Peter Burtwell and Anthony Salmon.

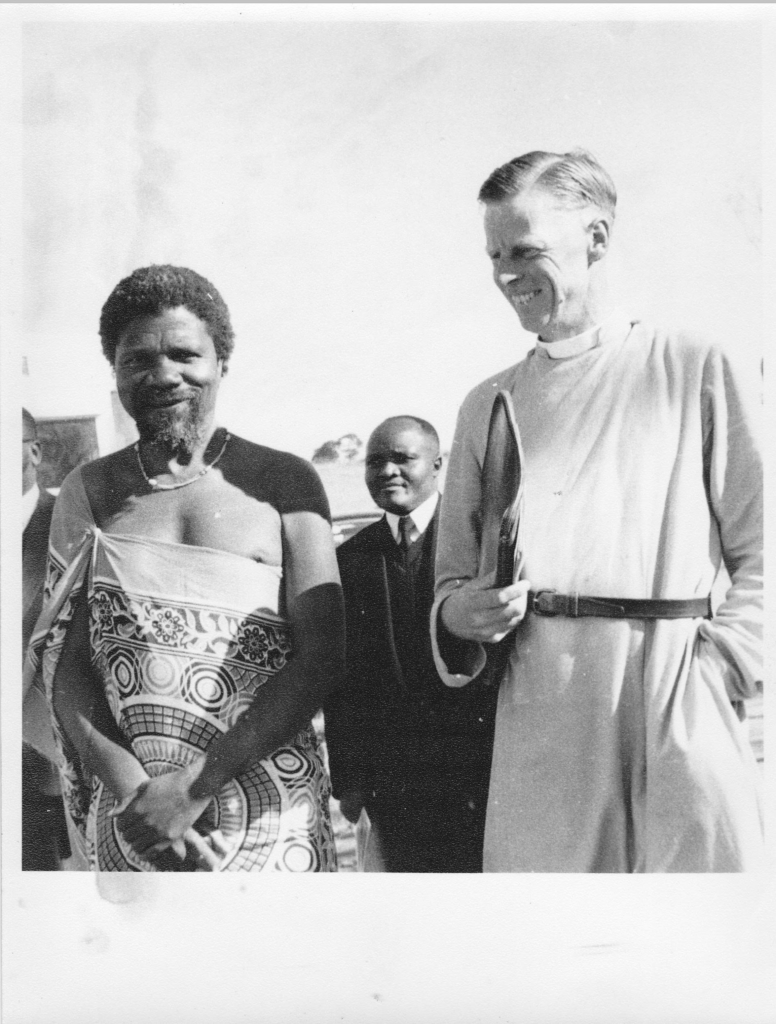

Sobhuza was a wise ruler in an age when autocracy was already out of date. He moved with ease in and out of traditional Swazi culture and language into the modern world. Fortunately he agreed to attend my unveiling and came with his indunas (advisers) in colourful Swazi dress and an appropriate wife out of the hundred he had acquired. He spoke perfect Swazi and English. Before the feast of two whole beasts was devoured, Sobhuza graciously welcomed me but said pointedly that the Anglican Church had so far done very little with the land his father had given us. His followers seemed to agree. I chose a Swazi proverb with which to open my reply. ‘The mouth can cross even a river in flood.’ If your people and we can work together, there may be something to see in a few years’ time. Six years later I referred to this meeting when speaking at the official opening of St Christopher’s school.

Fortunately I had learned to sing mass in Zulu from the Mandebele congregation at Broederstroom, Pretoria. They had migrated 550 miles from Zululand in the mid-1600s and had clung tenaciously to their language, though surrounded by Sotho-speakers, whose language was as different as German is from English.

Members of the local community joined us for worship on Sundays. As a young girl Jean Ions (who later married Jack Dobson) recalls: We used to go to Church on Sunday at the Mission. It was the little old church in its original state. It was kept clean and neat by the local ladies. The one thing they had to do before each Sunday was “polish” the floor which meant getting some fresh cow-dung to smear on it and polish it. Some of the “ladies” didn’t fancy it! I just remember thinking what a pleasant smell it gave off and how meticulously they polished it.

The Malkerns Valley was dramatically beautiful. To the west, the slopes of the Drakensberg mountains, which Usuthu Forests (a wing of the Commonwealth Development Corporation) was just beginning to cover with pines. Eastwards you looked across the lowveld to the Lebombo mountains, 50-60 miles away marking the border of Mozambique, then known as PEA (Portuguese East Africa). Alongside us flowed the Great Usuthu River, which provided constantly replenished building sand. Work was just beginning on the Malkerns irrigation scheme, which was to turn the whole valley into rice fields and citrus orchards. Over the next 20 years it would provide all the electricity the country needed and irrigate vast acres of rice paddies in the lowveld.

A Zulu priest, Wilmot Jali was in charge of the parish when I arrived and was a huge help to me. His wife Rosamund was the very competent head of the primary school. Bit by bit we managed to get the church going again. The parish covered the southern half of Swaziland but little was happening except at the Usuthu, Mankaiana and Hlakikulu. There was an old and decrepit mission station at Endlozana, just across the Transvaal border in South Africa. I had a motor scooter – a Vespa, and then a Lambretta – and went off on a hundred and twenty mile trip once a month.

Most Swazi followed African Traditional Religion and were polygamous. Large numbers of men went as migrant labourers to the Johannesburg gold mines, which then employed 350,000 men, creaming off the most go-ahead from Swaziland, Lesotho, Zululand, Mozambique and Malawi.

Men and boys did the ploughing with oxen, other agricultural work was done by women. As the boys were herding cattle for the five months when the maize was growing, few of them got very far at school. The top classes were mainly girls: western culture came into Swaziland through women. It was the other way round in Malawi, where gardens are tilled by hoe and that is women’s work, so the boys went to school.

Stephen Makandanje

One of our ‘bush-brotherhood’ team was a Malawian, Stephen Makandanje. He had walked 1,000 miles to Swaziland in search of work in 1915 and had worked all his adult life as a hospital orderly. He built a church in Hlatikulu with his own hands, having asked to be on night duty at the hospital so that he could work on the church during the day. It took a year to mould and bake the bricks, another year to build the church building and a third year to build up a thriving congregation.

I thought Stephen would make an excellent priest and asked him if he would like to be ordained. He said. “No, that would spoil it all.” I asked him. “Why?” He said, “The work of God has to be done from your heart. To be paid for it would spoil it.” I replied, “If I asked the bishop to ordain you as a priest and promised to pay you nothing, would you accept?” “Father, that is what I have always longed for.”

Stephen inspired me with the idea of voluntary ministry. Years later when in Malawi, diocesan synod welcomed the idea and when we finally left in 1981, many of the clergy were voluntary priests.

Usuthu pineapples 1956

I was due to go on leave in 1956 to Australia – I had not seen my family for seven years. We had just planted a quarter of a million pineapples. I was Chairman of the Swaziland Pineapple Growers Association.

Nobody had grown pineapples in Swaziland before; the pundits said they would only grow within ten miles of the coast. The entire pineapple industry was near Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape, five hundred miles south. We had started irrigation farming, using water from the Great Usuthu River and planted some pineapples to see how they would do.

We had a lot of other things happening at the time, including starting a secondary school, and I was doing most of the farming. Anthony Molesworth knew nothing about it so it was essential that somebody be found to look after the farm for six months while I was away. We were employing a dozen or so Swazis but they needed direction. We had a long meeting and couldn’t think of anyone, when Anthony said he knew a chap who used to be in his scout troop in Tyneside. He had just been doing his military service in Kenya. He was probably at a loose end as he had just lost his job. He was working underground for the British Coal Board.

I said it sounded just the job for fruit farming and building in Swaziland, write and see what he says! We did not hear anything and then we had a cable from the Canary Islands saying, “On the way. Arriving in Cape Town next week.” And so arrived Jack Dobson, who was later ordained priest and then became Archdeacon of Swaziland.

The pineapples have done extremely well and it is still a major industry of the country. The people who said they would not grow with us did not know what they were talking out. Never believe experts! The farm next-door was owned and run but not directly managed by the Director of Horticulture for South Africa who lived in Pretoria. He was responsible for all the pineapple growing in South Africa and was one of the initial growers of pineapples. He went bankrupt! We did not make a lot of money but we did not go bankrupt.

For various reasons, partly to do with the factory and partly due to the cost of exporting and finding markets, the pineapples were not a financial success but profits were good enough to keep the industry going. The Director of Horticulture, at one stage, was employing one hundred people on his farm trying to pull out the weeds by hand, which was not much fun with all the spines along the edges of the fruit.

My leave in Australia taught me much. I found that their methods were totally different from those in South Africa. The pineapple has a very vulnerable root system. They are small and fleshy so are easily broken off and then the fruit ceases to grow, although they may live. It is impossible to hoe so they were planted feet apart and weeds were left to melt around the plant. In Australia they plant them half the distance apart, only twelve inches, with the idea to get them to grow together as quickly as possible so they form a total shade over the ground to prevent weeds growing. They also applied a weed-killer spray, which kept the weeds at bay for six weeks. If the fruit was growing well in six weeks a canopy grew over the ground preventing weeds growing. We planted our pineapples using this method and they did very well. A Pineapple Growers Association was formed and I was made its Chairman.

There was no problem getting the produce to a port as the railway was being developed primarily to take the products of the forest that had been planted along the Drakensberg Mountains. Maputo, the new name for Laurenzo Marques, was one of the best natural ports in Africa. A river with sixty feet of water right along the wharfs, completely protected by islands.

I saw Swaziland from the air in 1980 and, as we circled the airport, all we could see was blue-grey – pineapples. A much, much bigger industry than when I left it twenty years earlier, now stretching miles along the Malkerns Valley.

St Christopher’s secondary school

When I was in Australia in 1956 people generously gave enough money to get the school started. Jack Dobson, the coal-board man and a surveyor, was in charge of the building as well as the farming. The school was built on a fairly steep hillside. The amount of soil we had to excavate was considerable and we had no proper excavating materials at all, but we did have a tractor at this stage.

Jack built St Christopher’s for 120 boys for something under £10,000. I think it was originally for 60 boarders and expanded to 120 students, just 100 yards from where our houses were. A glorious view looking right down the Mzutu valley, with the mountains in the distance.

Jack was the best man at my wedding in Malawi in 1962.

The Paramount Chief came to the opening of the school in 1959. We were very glad that he had marked the occasion by sending one of his sons as a student.

On leave to Australia

SPG (The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel) allowed missionaries their second ‘furlough’ after seven years. The next would be after ten, then no more. You belonged now to the local Church. For my leave in 1956 I headed for Australia, leaving Anthony Molesworth in charge with Jack Dobson looking after the farm. Community life was what interested me most. The Usuthu semi-brotherhood was good but something was lacking. Perhaps we could learn from the ashrams (mini-communities) of India, and from the West Queensland Bush Brotherhood, where I hoped to spend a fortnight.

I was keen to see something of Asia, where our family history began. I sailed for Australia on a White Star cargo ship via the east coast of Africa, to Bombay (now Mumbai ). Two miles off Zanzibar the wind already carried the scent of cloves.

At Mombasa, Arab dhows were in the harbour. I watched one being repaired. The Arab boat-builder was using a drill operated by a bow, rather like that for a violin. The bit span backwards and forwards as the skilled craftsman moved his hand left to right, with the cord wrapped round the drill bit. I later saw exactly the same technique being used in Penang harbour. Arabs had been trading on both sides of the Indian Ocean from the time of Christ. The bow-drill, like Islam in Indonesia, Malaysia and East Africa, was one of their legacies, as was the Swahili language, made up from Arabic words and Bantu grammar. At Karachi an enormous squatters’ camp provided a kind of temporary home for perhaps a hundred thousand Muslims, some of the millions who had left India for the new state of Pakistan established in 1947.

At Tiruppattur station – mid-way between Bangalore and Madras – I was glad to find an ashram bullock-cart waiting for me. The ashram church was in the style of a South India Hindu temple. It had a white tower covered with carvings, not of Hindu deities but of trees and wildlife. I found nine members of the ashram, but some were out in villages. They lived in a community of eighty or more, the rest being students, mostly Hindu, who had come to spend their vacation working with members of the ashram. The two founders, one Scots and the other Tamil, were both eye-surgeons and had met during World War I. From time to time the ashram divided into small groups who would each stay in one of twenty or so villages, looking for new patients with eye problems and helping with other community needs, such as clean water.

At sunrise each morning, all of us – Hindu volunteers, ashram members and myself as a guest from Africa – spent an hour in silent meditation, cross-legged on an inner verandah that surrounded a patch of grass and a palm-tree. I think I felt nearer to Jesus and his Twelve than at any time of my life.

Gandhi once visited Tiruppattur. When he left, he said to the Hindu members of the group, “This is the kind of Christianity you should be afraid of!” The rest – symbolised by the very English parish churches I saw, even in villages – would have no future.

I left by bullock-cart after three days, caught another train and in Madras met a South Indian Bishop. I disgraced myself by calling him “My Lord” and trying to kiss his ring. I thought this was what one did to bishops. I received a gentle rebuke, “This is the Church of South India. We don’t have Lords.”

By train again down the Coromandel Coast (what a lovely name!) and then the long Adam’s Bridge that spans the 20 miles of the Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka had just won its independence and my hostess took me to the top of a mountain overlooking the beautiful city of Kandy. The results of the election of Sri Lanka’s first President were about to be announced. There, 500 feet below us, the whole of Kandy was in a party mood – fireworks, music and dancing. Then the news broke – Sri Lanka’s first Prime Minister would be Solomon Bandaranaike, leader of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party. He was succeeded by his wife.

I continued on my passage by ship to Fremantle, the first bit of Australia we saw as a family when we arrived as immigrants 30 years earlier.

Impopotha and outreach work

It was good to be back at the Usuthu Mission after a worthwhile leave.

Fifty years ago one of the early missionaries found a little Coloured boy, the son of an English colonial officer and a Swazi woman. He put him on his horse, clothed him, taught him and when was grown up sent him off to find his way in the world, just saying: “When you get a chance, do something for the Church in return.”

This man, now grey-headed, said that he had bought a little farm and wanted to give a piece of it to the Church.

So we built the little church of St Anthony on the small hill overlooking half of Swaziland. At one end is the round apse in the chancel. It was closed off by two big doors so that it could also be used as a school. Outside the building was whitewashed so it could be seen from miles away with its great cross of sky-blue tiles.

On one visit Ruth, the mission Land Rover, was towing a big trailer picked up on a scrap heap and we nearly got stuck in the mud several times but Ruth carried on for 30 miles. It was nearly dark when I arrived at Mpopotha, a hot meal was waiting at William’s house.

Mission work and Siswati language

We did quite a lot of active mission work during which the number of church congregations grew from two to twenty-five. Our priority was to build up a Swazi priesthood. I think there were only one, possibly two, Swazi priests in the entire world at that time. There were a few Zulu priests, one of whom was Fr Jali, a member of the team at Usuthu. The Zulu language is quite different from the Swazi language and this had to be an indigenous church so one of our first jobs was to find candidates for the priesthood.

We found a couple in the secondary school we had in Endhlozane, which was 100 yards outside Swaziland in the Transvaal, and they were trained up. I forget whether they were both ordained but one definitely was and there were others later on. One of our fights was to have the Swazi church recognised as independent of the Zulu church.

They had nothing much in common, except we were speaking the Zulu language in church because the Zulus had a greater profile in British consciousness and both of these places, you might say, had been under British administration. Zululand was attached to Natal, and Swaziland one of the three High Commission Territories – Swaziland, Basutoland (Lesotho) and Bechuanaland (Botswana).

The British had prescribed that Zulu should be the language taught in schools and when education first arrived in Swaziland, Zulu was the language imposed. It seemed to us quite ridiculous that people should be speaking a foreign language on top of another language that they had to learn as the main business language – English. I felt there was a place for people to have two languages, but not three. People would always need English as being the language of higher education, also being the common language of the black population of Southern Africa. Swaziland is necessarily a part because it is, physically and geographically, almost with South Africa. The same applied to Basutoland (Lesotho) and Bechuanaland (Botswana).

The other language is the one you spoke as a child, the one you say your prayers in, make love in, the intimate language of the heart, and that has to be the real language. Swazi is not the correct name as the letter Z does not exist in Swazi. The language is called Siswati and people do not refer to their country as Swazi, it is Kangwane, the name of the founder of the nation, who originally migrated from Mozambique somewhere about the end of the eighteenth century,

There was no good reason for Zululand and Swaziland to be in the same diocese. The Swazis suffered from having a bishop 300 miles away in Eshowe in Zululand and saw him twice a year. I was a member of the Standing Committee and had to make a 600 mile round-trip for every meeting.

So we did two things. One, to try and establish the Swazi language of Siswati. There was a small local newspaper mainly in English but with a page or two in Zulu. They agreed to print anything we could produce in Siswati. We invited contributions in Siswati – folk tales, autobiographical pieces, anything. There was an enthusiastic response, even though few had ever seen written Siswati before. The only printed material in existence was a catechism of the 1860s, long out of print, and a grammar book from the Department of Linguistics at Pretoria University in Afrikaans (Cape Dutch) and Siswati.

Superficially Siswati is a bit like Zulu but there are important differences, for example, the letter ‘z’ is replaced by a ‘t’ and all nouns begin with a consonant, not with a vowel as in Zulu. The vocabulary is perhaps 15% different.

Simon Nxumalo

One set of contributions to the local paper was outstanding. Whoever wrote them was an artist with words. One was about a thunderstorm. “Great black clouds filled the sky; the rain came down and then the hail and the herd-boys shivered and pulled their skin cloaks over themselves.” It was brilliant writing. I said to Jack, “Let’s go and dig this man out.” He had written from a little school on the top of the mountains in Usuthu Forests, perhaps 20 miles away. We went off on a Sunday afternoon to find him.

Simon Nxumalo was a teacher in his mid-thirties and excited by our visit. He pulled out a tin trunk from under his bed full of Siswati manuscripts. He hadn’t been able to find anyone interested in reading them. We picked out the best and printed them week by week. There was a centre in Johannesburg promoting Southern African languages. They offered to take Simon Nxumalo and train him to lead a Siswati team and to write the necessary materials. In due course he came back, published the first literary books in Siswati and launched a literacy campaign on a national scale.

Siswati later became the official language of the country. The prayer-book and the New Testament have both been published in Siswati.

Off his own bat he also set up the Sebenta Society – self-help movement. ‘Sebenta’ means ‘work’ in Siswati. I left Swaziland at this point and am hazy on detail but I know he went into politics and ran a party in opposition to the Paramount Chief – a brave thing to do. He finally did a deal with the King’s party and ended up as Deputy Prime Minister. Right out of the blue, some 8 or 10 years ago, he telephoned me from Swaziland and we had a long talk about AIDS. He was then the Chief Scout of Swaziland, and as I had been a former Commissioner for Training, I recall suggesting that he use the Scout and Guide movements as a way into the need for behaviour change in the anti-AIDS campaign.

As part of our campaign for recognising Swaziland as an independent country in a Zululand Synod that was being held in Swaziland, we called for the name of the diocese to be changed to ‘Zululand and Swaziland’. Bishop Tom Savage was not best pleased. Now he had to sign every document with the cumbersome signature ‘+Thomas Zululand and Swaziland’. It was another eight years before Swaziland became a separate diocese with its own language, history and culture, no longer the poor relation of South Africa’s Bantustan, KwaZulu.

Bernard Wrankmore

We welcomed a variety of people and groups to work with us at the Usuthu. One of the most colourful was Bernard Wrankmore. A letter came from the Archbishop of Capetown saying, ‘We have an excellent but unusual man in mind for ordination. Could he come to you for some of his training?’ So Bernard joined the team. He had worked in several countries, amongst other things he had been a camel-driver, organiser of prize-fights and country-dancing.

I travelled with him to Capetown and found myself sitting in a small dinghy while Bernard searched the seabed for abalone – large edible snails. I was given a hand-pump to supply him with air. He had no mask and told me there was a limit of thirty seconds without air, after that he would be drowning. It was a terrifying experience. It was wonderful to see him again at my wedding, where he fixed our departing Land Rover, three times!

This newspaper article summarises his life.

I learned much from the people of Swaziland and the team with whom I worked for ten years and was sorry to leave for Nyasaland in November 1961.

— End —