Editors: The Diocese gained from international contacts as it became more self-reliant. This section summarises some of them.

Lambeth Conference

Bishop Josiah Mtekateka and I headed for London in August 1968 for what for both of us was our first Lambeth Conference, chaired by the loveable, holy and wise Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey. We arrived full of fears. Would the moves towards unity in our brash young Province be slapped down? Would we appear foolish in the eyes of the young and concerned?

The first few days didn’t help. The mediaeval pageantry, the trumpets, the scarlet and white – what had this to say to the Black ghettoes of apartheid in South Africa?

The group of sixteen for which I had opted, dealt with the laity and I had been made secretary. Could we meet with laypeople who could tell us what their problems were? Security said “No!” We had been provided with one layman and one laywoman from among the consultants in case we wanted to see what they looked like. We circumnavigated this obstruction. Our first witness, a merchant banker, told us that at forty-seven he was the oldest member in his firm. A quick calculation on the first names in Who’s Who at Lambeth showed an average age of sixty-two.

There were more hopeful signs. Only one bishop appeared in old fashioned leg gaiters on the first day, and he not again. Most of us lunched in one of the then popular pancake bars – there were no central dining arrangements. Bishop Neil Russell’s motion calling for radical reassessment of titles and forms of honour was carried by applause without dissent.

Michael Ramsey’s opening sermon foreshadowed themes that would recur again and again. God was a God of compassion, concerned about all human life, not just our religious activities and concerns; our faith would be tested in what we did about peace, race and poverty; Anglicanism was not a separate encampment but a bright and unselfconscious colour in the Christian rainbow; unity did not mean combining Churches as they are now, it meant radically transforming them.

In my report to our diocese I wrote:

Christ requires those who exercise leadership in the Church to be servants of all. We bishops have often obscured this truth. What we do and how we do it should remind people of Jesus the Servant.

There is nothing new in this. Bonhoeffer in a Nazi prison, Fr Damien on his leper island, St Francis with his begging bowl, all tell us about Christ, the Man for Others.

Many of us still think of hospitals and schools as things done for us by kind friends in the West. We have to learn that these are done by us for our neighbours, most of whom are Muslims or of African Traditional religion.

Our group on the laity said in their report that the Church’s task was to challenge all that cramped fullness of life. We called for active support for all who struggled for a fuller and better life for humanity, including Marxists and Humanists whom many Christians saw as public enemies. We called for dialogue with those whose expertise in psychology, economics, journalism and the social sciences could lead to fullness of life – irrespective of their faith or lack of faith.

We were encouraged to develop the ministry of voluntary priests which Stephen Makadanje had exemplified in Swaziland and Gerry Hotblack in Malawi. Lambeth said, “Go ahead. This is consistent with scripture and the early Church. There is no evidence that recruitment to full-time ministry has been affected.”

The ordination of women priests? Surely, some said, this was alien to the patriarchal structure of much of Africa? Yet the bishops from our neighbouring Province of East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania) told us they had twenty women in training to be deacons and that as priests they could be a way of restoring a full sacramental life to dioceses where twenty or thirty congregations shared one priest.

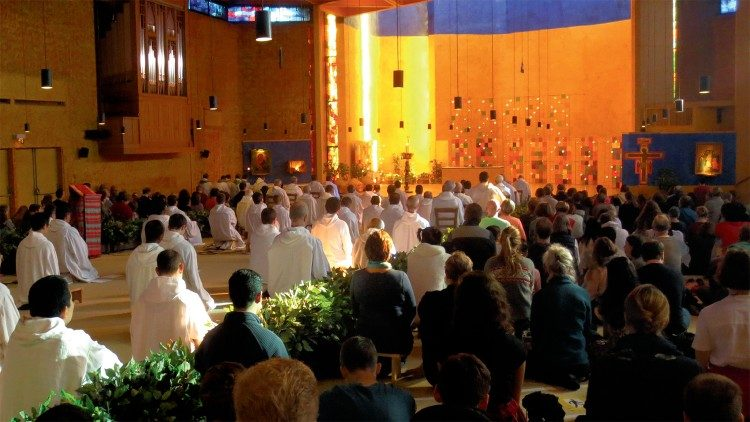

Taizé

I spent a week-end at Taizé on my way back from Lambeth. It is a small rural village in Burgundy, France and an inspiring place to be. A living example of reconciliation and unity with this wording over the entrance:

All you who enter here be reconciled

The father with his son

The husband with his wife

The believer with the unbeliever

The christian with his separated brother

The ecumenical community of ninety Brothers was founded in 1940 by Brother Roger Schultz. Most of the Brothers were scattered all over the world, working together in pairs in Africa, South America, USA and elsewhere.

When at Taizé I was deeply saddened to hear of the death of Christopher Lacey. I knew that he was seriously ill with a gastric ulcer but never dreamed that it could be fatal. There is more on Christopher Lacey in the Appendix.

Uganda and Kenya

From Taizé, I flew to Uganda where Archbishop Erica Sabiti, whom I had met at the Lambeth Conference, was extremely generous and we visited some of the work that was going on.

The Church in Uganda was almost wholly African and vast numbers attended. The Church Missionary Society had been led by prophets such as John Taylor and had been preparing for African independence for twenty years. Young clergy had been trained for leadership, large churches had been built in strategic places which could become cathedrals. There was now only one white bishop out of ten and only a handful of missionaries.

There were, of course, plenty of problems. The clergy were paid by their congregations, nominally £12 a month but half were not receiving that. Anglicanism had come in one form only and almost everywhere prayer books used the old 1662 format translated into the local language despite the efforts of Leslie Brown, the last white Archbishop, to introduce a new liturgy based on the lively South Indian rite which he had devised.

From Uganda, I went on to Kenya on the invitation of Bishop Obadiah Kariuki, a veteran of the Mau-Mau struggle, who had taken part in my consecration seven years earlier. I had never seen a church so alive or growing so fast. Here, also, the clergy were paid by their own congregations, but at £25 per month. I was told that they all received their money, though this may not have been true in less developed areas.

.