Soon after arriving in Nyasaland I called on the Director of Medical Services. He had just received his budget from the Federal Government in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia. Nyasaland was at this time an unwilling member of the Central Africa Federation of Southern/Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Harold Macmillan had seen the Federation as a way of dealing with the poverty of Nyasaland without having to spend very much money. The Director threw the papers on to his desk. “I am expected to provide medical services for the whole of this country of three million people on the same budget as that of Salisbury Hospital in Southern Rhodesia.”

This unequal division of Federal funds for health in 1958 are quoted in Michael and Elspeth King’s Story of Medicine and Disease in Malawi:

Population Health expenditure African admissions Govt Hospitals

Nyasaland 2.8m £715,000 64,000

S.Rhodesia 2.7m £3,655,000 475,000

The figures illuminate the reasons for my predecessor, Bishop Frank Thorne’s opposition to the proposed Federation, which was British policy throughout the era of Harold Wilson’s and Harold Macmillan’s governments.

Malaria

In 1897, Ronald Ross proved the connection between malaria and mosquitoes. He wrote:

I find thy cunning seeds O million murdering death.

A few years later he passed my mother for service as a nurse in Malaya, despite ‘a dicky heart’, as she used to call it, from teenage rheumatic fever. In Malawi, sixty-five years later, we were fortunate with malaria. For twenty years, two paludrine a day and one daraprim a week gave all four of the Arden family total protection, but by the time we left in 1981, malaria was developing resistance to anti-malarials. For Malawians, this was not an option as it destroyed the immunity which protected most adults from the severe outcomes of malaria.

When our son Chris went back in 1988 to finalise his medical studies he confirmed the increasing resistance to chloroquine and other drugs.

By the age of five, most Malawians have developed sufficient immunity to make malaria a major nuisance but not a life-and death issue, except for the very young and pregnant women, for whom it can be lethal. ‘Perma-nets’ – permanently impregnated nets – and the spraying of internal walls with DDT are today the only defence.

The first UMCA (Universities Mission to Central Africa) doctor, Robert Howard reported on arrival on Likoma in 1899:

“In the past six years, twelve missionaries have died and six were invalided home.”

Usually this was the result of ‘blackwater fever’, an advanced stage of malaria. As a versatile builder, carpenter and harbour-master, he built Nkhotakota Hospital in 1902, followed by Malindi Hospital in 1908.

Nurse Kathleen Minter describes Nkhotakota Hospital in 1899:

“It was many months before anyone would come for treatment. My first patient was a slave wife who had fallen in the fire, burning her arms and knees badly. She had been lying there for five days. No one around would help her. Neema, our one-legged cook, is the first African here to wear a wooden leg.”

A footnote: Robert Howard and Kathleen Minter married in 1910 and were exiled to Zanzibar for breaking the rules of UMCA by ‘committing matrimony’.

Medical Assistants

Editor: From the beginning (1890s) the mission trained local people to work alongside the doctors in order that they could practice independently. Malawi had so few qualified doctors that Medical Assistants were and are essential for delivery of the health service.

Dr Howard realised the urgent need to train African staff and in 1900 asked Edward Nemeleyani to take up medical work. Edward was awarded the Order of the Epiphany (an award given to lay people in the Province of Central Africa Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe) for outstanding service just before I arrived.

Edward Nemelayani and Swinny Mtiesa were the first Medical Assistants to take charge of a hospital, Edward at Nkope, Swinny at Malindi, which is where I found him in 1961. Edward died in 1968 after sixty years of devoted service.

Swinny Mtiesa

Swinny Mtiesa began his training at the UMCA Hospital at Liuli in Tanzania, followed by four years at the Scottish Mission Hospital in Blantyre, the predecessor of the present Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Following the Chipembere rebellion in 1965, people in and around Malindi were arrested and detained without trial. Swinny, one the gentlest of people, was taken into political detention, where he remained for many years. A large number were held for years, some in solitary confinement, under appalling conditions. When speaking with people after their release, I used to marvel at their lack of resentment and bitterness over what they had been through. Swinny personified this generous spirit.

Soon after his return to the hospital in Malindi, Swinny realised that his eyesight was failing so travelled the 120 miles to see the Israeli eye specialist at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre. After careful examination, he was advised to return to Malindi and learn Braille as he would soon have no sight. A disappointed Swinny returned to the people and hospital he loved, wondering how long he would be able to continue to serve them. A man of deep faith, anchored in prayer, who began and ended each day in the hospital with prayers with staff and patients, Swinny prayed for guidance and help.

A few months later he had a dream. He should return to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital so that his eyesight could be cured by an American doctor. Not knowing why but sure that he should follow his dream, Swinny went to Blantyre. When he arrived at the hospital, the Sister in charge of the crowded ward, who respected his many years of work as a Medical Assistant, put him in a private room.

The next day, while Swinny was lying on his bed, he heard the voice of a visiting eye-specialist asking, in an American accent, “Who’s in this room?” He was told that Swinny was beyond treatment. The visiting consultant said he would like to see him anyway. After examining Swinny and listening to his story, the consultant said to him, “I can’t promise anything but I did read in a recent journal that massive doses of vitamin B12 occasionally help people with your condition. Let’s try it.” Swinny was not only cured but continued working for many more years.

Late one night, I was staying with Swinny at Matope, where he was in charge of the Health Centre – a hot, humid place beside the Shire River with very active, king-sized mosquitoes. There was a rap at the door. Some miles away, a family had gone down with cholera, then a new illness to us. Swinny left at once and popped around to a friend with a pick-up truck. Half an hour later, he returned with half a dozen adults and children writhing in agony. He set up saline drips and I went to bed. At sunrise the family was laughing and chattering on the ground beside the pick-up.

The following year, I met a Muslim man whose problems had defeated the government hospitals in Zomba and Blantyre. He was saying that Jesus had cured him through Swinny’s hands and now he was visiting all the Muslim homes in the Matope area with a Chichewa Bible New Testament saying, “This will tell you about Isa (the Arabic name for Jesus) who has healed me.”

While at Matope, Swinny’s diagnostic skills appeared on the front page of a national newspaper in the shape of a glass jar containing 988 worms. A man had travelled to see Swinny from Blantyre, where people had been unable to diagnose his problem. The worms were his reward. Each time we have returned to Malawi, we have visited this saintly man, though in 2005 he was nearly blind and very old.

Dr Art Johnson his wife Nan

A few months after returning to Nyasaland from our fundraising tour of the States we were desperate for a doctor to help build a hospital to replace the one built in 1913, which was higher up the hill at Mkuli. St Luke’s Hospital was to be nearer the main road at Malosa.

I said to Jane, “Do you remember a doctor at Houston Cathedral saying he would consider work in Nyasaland? A slightly built man I think?”

This led to Art and Nan Johnson (she was a nurse) and their three children coming to St Luke’s early in 1965. I think Art was the biggest man I have ever met, with a generosity to match. Nan was only slightly smaller. They arrived with a huge metal container packed with everything for an operating theatre, laboratory and much else for the hospital they would help to plan and build.

The metal container was so large and so heavy that a slipway had to be dug into the ground so that the lorry carrying it could reverse down into it and the container manhandled off with wooden poles. The container is still at St Luke’s, housing the standby diesel generator.

By the time they returned to the States in 1968, St Luke’s consisted of an operating theatre, laboratory; and male and female wards. They were a wonderful pair and poured out their energy, expertise and love on everything and everyone.

Art and Nan Johnson were so impressed with Swinny Mtiesa’s medical work that they invited him to visit them in Texas in 1969.

Training Midwives

The systematic training of Malawian midwives in the Diocese was later than that of medical assistants. It began with Margaret Woodley at Nkhotakota in 1941 at St Anne’s Hospital, which has always specialised in children and maternity care. The UMCA history quotes Margaret:

The Midwives Training School began with five pupils. I had arranged the official opening for 26 August at 11.00a.m. but at 10.30 there was great excitement, “Come quickly, we are going to open the school with a baby!”

Three hundred and forty-seven babies were born in the hospital in 1946 and the Training School provided a steady stream of midwives. In 1963, I wrote to my brother Felix, a paediatrician in charge of the Children’s Hospital in Brisbane:

“We have two UMCA fully-trained nurse-midwife tutors overseeing nurse-midwives in eleven hospitals and health centres dealing with 500,000 outpatient attendances a year.”

In July 1970, a new Student Midwives’ Hostel, designed and built by USPG missionary Michael Ryan, was opened by the Netherlands Ambassador, whose government, together with the Beit Trust, had given the funds. Japanese nurses, under a scheme similar to VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas) joined the training staff in 1973. For a number of years until his death in August 1979, Dr George Kunkwenzu, a dedicated Christian and much-loved doctor, was in charge of St Anne’s and its Training School.

Christian Health Association Of Malawi

Clearly, we needed proper training for nurses. But how and where? And who would staff it and pay the bills? The problems seemed beyond solution. Then Janet Lacey, one of the founders of Christian Aid, responded to an invitation to come out and stayed for a week visiting many of our health centres and hospitals. She gave us wise advice:

“Get together with all the other churches involved in health work, then send a letter from all of you to the Christian Medical Commission (CMC) in Geneva and ask them for someone to come to see the challenges and suggest a plan.”

We did exactly that. As far as I know, Catholics, Anglicans and Presbyterians had never had a joint meeting in the seventy and more years they had been working in Malawi, let alone the Seventh Day Adventists. Within a month or so they had all agreed to an invitation being sent to the CMC and in August 1965 Dr Kames McGilvray came. He visited every one of the twenty church hospitals and, in two weeks, secured their agreement to work together in the body now called CHAM – Christian Health Association Of Malawi. He spent his last night with us, having come from a hospital with a strong evangelical tradition. “I was asked by a missionary sister, ‘Does this mean we might have a Roman Catholic nun working in this hospital?’ I was so exhausted I just said, “Don’t worry, my dear, she wouldn’t stay long!” We were told later that CHAM was the first such body in the developing world.

The first Secretary of CHAM was Hugo Niemer, a tall gentle doctor from the Netherlands with a long grey beard. Under his guidance, CHAM forged much closer links with the Ministry of Health, which, ten years later, agreed to pay the salaries of all qualified Malawian staff. Its first conspicuous achievement was setting up ten nurse training schools, one at St Luke’s, Malosa, in the Southern Region and one at St Anne’s, Nkhotakota, in the Central Region. Unfortunately, Dr Niemer’s work came to a sudden end a few years later when at midnight his car hit the weekly train at the Balaka level-crossing. Both Hugo and his daughter, who was driving, died instantly.

In the 1980s, the Nursing Council decreed that midwives must also learn general nursing and St Anne’s Training School came to an end. Everyone applauds the raising of standards but these have done little to end the high rate of maternal death in Malawi. In 2006, 807 mothers died in childbirth. In Britain, the figure was 11 per 100,000 live births. The training at St Anne’s may have fallen short academically, but it did include two months at an outlying Health Centre with no electricity. Their experience was learned the hard way, in keeping with the hard life most Malawian women face.

In a country where only 4% of the population had access to electricity, the experience of delivering a baby by the light of a paraffin lamp was useful. This was far from ideal but it ensured that student midwives experienced the reality of childbirth in a village house which is the way most Malawians of today have come into the world.

Update (2021): The Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) is the largest non-governmental healthcare provider and the largest trainer of healthcare practitioners in Malawi. CHAM provides 30% of Malawi’s healthcare services and trains up to 80% of Malawi’s healthcare providers.

Susan Cole-King

Susan Cole-King and her family came to Malawi in 1964. Her husband, Paul, was the first curator of the newly established museum in Blantyre and wrote a number of excellent booklets about the history and pre-history of Malawi. Their four children overlapped with our two in ages.

Susan had had a vivid spiritual experience while still at school, which led her to train as a nurse. After completing her training, she met Dr Banda, then practising as a doctor in London, following which she decided she would train as a doctor and work in Malawi. Before arriving in Malawi, she had been stimulated by the ideas of Professor David Morley, known as the Under-5 movement. He said that the lives of millions of children could be saved and vastly improved by monitoring those under five years of age, teaching mothers about nutrition and childcare and immunizing children against killer diseases that killed and crippled children all over the developing world.

When Unicef began to publish their annual State of the World’s Children reports, Malawi was seven places from bottom in a league table of all countries in the world. In Malawi, 320 out of every 1000 children died without reaching the age of five. All the countries ranked lower than Malawi were at war, recovering from war or in the Sahel, the semi-desert region south of the Sahara. This laid the foundations for the continuing improvement in childhood mortality that we still see today.

Quietly, Susan, now employed by the Ministry of Health, put David Morley’s theories into practice in a rural clinic near Chiradzulu, in the Southern Region. Within three years, the government was convinced of their soundness and the Under-5 campaign was launched with a series of seminars for health workers at the newly founded Chilema Ecumenical Lay Training Centre. A year or two later, Susan was given the job of launching the Under-5 clinic movement on a national scale. The fruits of her pioneering work, along with that of hundreds of Malawians, are that, in 2005, the death rate of children under five had fallen from 320 to 189 per 1000.

In 1971, I was given a report on child health in the Domasi area, a small part of the Lake Chirwa plain which I could see every day from my study. The writers had interviewed 171 women about their children. Between them, they had lost 160 babies under one year old; a further 52 before they were five; and another 68 at a later age. The women recognised the symptoms of kwashiorkor – protein starvation, a common cause of child death. When asked what were the causes:

143 said ‘breaking a sexual taboo’

8 said ‘witchcraft’

25 said ‘don’t know’

3 said ‘the wrong kind of food’.

They all know only too well the symptoms of malaria, but only 19% thought it was carried by mosquitoes. 36% of these women had been to school as had 60% of their husbands.

This was not in a backwater. Zomba, until then the centre of government, was only ten miles away. Domasi, the leading government Teacher Training College, was adjacent to the area surveyed; Zomba Government Hospital and our own St Luke’s were within easy reach.

The report made me think furiously. We were proud of our schools, which had some 50,000 children attending daily. Were they learning any of the simple lessons for their own children to survive? A few days later, I was to give the address at the national interfaith service for the Independence Day anniversary in Kwacha Hall, Blantyre, as I had done several times previously.

The address, attended by all the Cabinet, would be broadcast throughout Malawi. It was an opportunity to say something more than the bland platitudes customary on such occasions. I forget exactly what I said, but it included the gist of the report above, which I felt to be a challenge to all of us – churches, schools, hospitals and government. The result was unexpected. A motor-cyclist arrived the next morning summoning me to report to the Malawi Congress Party immediately. There I found most of the Party Executive awaiting me. I was not asked to defend or explain what I had said, just to understand that anything bordering on criticism was totally unacceptable, even if true.

The impetus of the Under-5 programme was unstoppable and the nurses and medical assistants at health centres and hospitals adopted it with enthusiasm. Whenever I visited one, I was told of new mobile clinics served by staff on bicycles. I would find nurses at out-patient clinics using the opportunity to teach Under-5 mums the basics of nutrition and protection against malaria. The task continues to be enormous.

Susan left Malawi after nine years to work at Sussex University. After a brief period with the World Health Organisation in Geneva, she became the Chief Medical Adviser to Unicef. During this time, she developed a wide understanding of HIV/AIDS.

Responding to a call long felt, Susan was ordained priest in New York in 1987. Taking part in the service were the Assistant Bishop of New York, together with Bishop Hugh Montefiore – who was a successor to Susan’s father Leonard Wilson as Bishop of Birmingham, and myself, providing a link with her beloved Malawi.

From left: Donald Arden, Susan Cole-King, Dennis Walter, Hugh Montefiore

On 6 August 1998, the anniversary of the atom bomb falling on Nagasaki, the Archbishop of Japan asked Susan to preach to the bishops attending the Lambeth Conference. This was partly an acknowledgment of her gifts as a preacher but also honouring her father, Bishop Leonard Wilson, who, as Bishop of Singapore, had been a prisoner of war in the notorious Changi jail where he had confirmed one of his Japanese jailers. Susan’s sermon on peace and reconciliation was said by many to be the highlight of the Conference.

Listening to Susan was James Tengatenga, Bishop of Southern Malawi. When Susan later asked him if there was anything she could do to help clergy and people in the diocese with the challenges they were facing over HIV/AIDS, he was clear that there was. For two years running, Susan spent several months in Malawi learning about the devastation of the pandemic and leading workshops for clergy and lay people. In these, she emphasised the important role for Christians in removing the stigma attached to AIDS and in supporting both those infected and the people looking after them. People who shared in these workshops said how much they helped build their understanding of Christian caring. Susan’s premature and sudden death in 2001 was a great loss to people in Malawi as well as to her family and many others.

Leprosy

I encountered leprosy the week after my arrival in Pretoria in 1945. All ‘lepers’ in South Africa were incarcerated in Westfort Leprosarium, on the edge of Pretoria. There were around a thousand people, mostly ‘Native’ with a handful of ‘Coloureds’ and ‘Europeans’. Their only common meeting place was the chapel, where Pip Woodfield and I took turns at a weekly eucharist. The accepted medical opinion was that leprosy was caught by contagion; you must never ‘touch a leper’. I felt brave when I occasionally shook hands.There was little else you could do when you spoke only one of South Africa’s ten languages and Katie was not with you.

Katie Volmink was a ‘Coloured’ granny, almost blind, grossly disfigured who had only one leg. For the people of Westfort, she was the personification of Christ. When anyone, of whatever race, felt death approaching, they would just say, ‘Please send for Katie.’ Within a few minutes, she was alongside them, holding their hands and would stay with them till they had died, even if it was forty-eight hours later.

At our weekly Eucharist, Pip and I spoke in English and Katie would translate into Afrikaans, a second interpreter into Tswana and a third into Zulu or Xhosa (which are remotely similar). The leprosy bacillus had ‘burned itself out’ in Katie, and after I left Pretoria she was discharged from Westport and spent her last years with her family. We kept in touch until her death.

UMCA had been concerned about the high incidence of leprosy in Malawi from the very beginning. Dr William Wigan, who served the people of Malawi for 36 years from 1911 to 1947, pioneered leprosy wards at Likoma, Likwenu, Malindi and Mponda’s. The German government admired his dedication so much that even after the outbreak of the 1914 war, he continued to supply medical care to the leprosy patients on Lundu Island, off Sphinxhaven, as Liuli was then called, while the Germans provided the food. “An impressive example of enemy co-operation” as Michael King describes it.

Because of UMCA’s initiatives and good work caring for people with leprosy on Likoma Island, Nkhotakota, in Tanzania and at Malindi, the government in 1926 gave UMCA 300 acres of land at Likwenu for a leprosarium. This adjoined the site where Malosa Secondary School, the Diocesan Headquarters, Chilema Ecumenical Lay Training Centre and St Luke’s Hospital, would later develop. In 1931, there were around 100 patients, including ‘burnt out cases’ who had settled on the edge of the mission land. The situation was similar in the 1960s, when Bill and Muriel Walters and Smythies Umande were in charge, supported by Lepra, the Leprosy Relief Association. Biti Kulanje was a leper village north of Malindi, where people who had recovered from leprosy were sent to live and cared for.

A sea-change came in 1966 with the arrival in Blantyre of David Molesworth of Lepra, with the incredible mission of wiping out leprosy in Malawi.

It was thought that 20,000 people had Hanson’s disease, as leprosy was now renamed to help it shed its biblical image. David told me that leprosaria were the problem and not the answer. People would never accept treatment if it meant immediate removal from their home and family, perhaps for life. If we went mobile, leprosy could be eradicated. David set up a programme in a hundred square miles around Blantyre and within a few weeks had more patients under treatment than all the leprosaria in the country.

Likwenu was the next area. Bill and Muriel Walters, together with Smythies Merikebu, adopted the new policy enthusiastically. It was made known throughout the Kasupe (Machinga) area that a medical worker would, without fail, be at a certain store, school or tree at a certain hour on a certain day every fortnight. His job was to supply two weeks’ worth of pills and hope.

Within two or three months, Likwenu and its satellite centres were looking after many hundreds of people with leprosy. Muriel died of cancer in January 1973 and was buried at the Leprosarium. Other churches and agencies, having seen the impressive results obtained at Likwenu and Blantyre, adopted the same strategy until the whole country was covered.

In 1976, Peter Garland, the former Principal of St Michael’s Teacher Training College, Malindi, was ordained as a voluntary priest, joined Lepra and was based at Likwenu. He was also given responsibility for coordinating transport for all Lepra programmes. This was largely push-bikes and motor-bikes to keep down costs while making it as certain as possible that one of the leprosy teams would be under that tree on time. A little later, David Molesworth moved to another country and Peter, who had moved to Blantyre, became an Archdeacon and head of Lepra in Malawi.

I was visiting Blantyre in 1995 when it was officially announced that leprosy was no longer a threat in Malawi. This was a huge achievement for all the field-workers and staff of Lepra and for Peter’s leadership. The odd case might occasionally appear – the borders with Mozambique were porous and the incubation period is long, but the campaign ended. The President of Malawi bestowed Malawi’s highest award, the Lion of Malawi, on Peter in gratitude for his huge contribution to the eradication of leprosy in Malawi.

The opening of St Luke’s Hospital – Malosa (video)

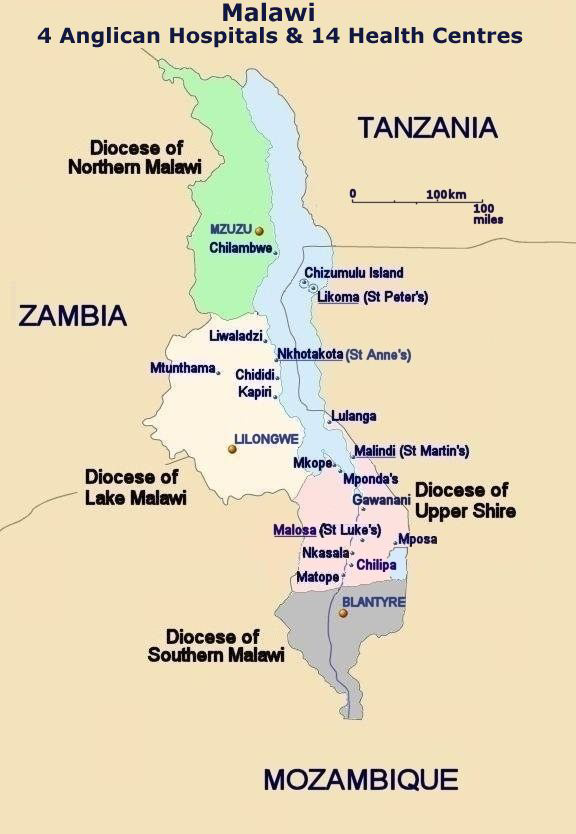

Hospitals and Health Centres – Map

By the time we left in 1981, the Anglican church in Malawi was responsible for four hospitals and 14 health centres.