Editors: Donald’s vision and energy were to encourage a sustainable and vibrant Malawian church which grew from and incorporated local values and traditions.

- A vision for Malawian leadership

- Deciding on future leadership

- Touring the diocese with the Archbishop

- New Archdeacons for Likoma and Ntchisi

- Searching for a suffragan bishop

- Learning Chichewa

- Archdeaconry Councils

- Anglican Council of Malawi

- Creation of the Diocese of Lake Malawi

- Malawi traditional religion

- Music

- Liturgy

- Islam

- Postscript

A vision for Malawian leadership

Two weeks after arriving in Malawi in November 1961, I wrote to the Swaziland staff that “the next bishop must be an African.” My first visit to Central and Northern Malawi – where four-fifths of Anglicans lived – made this an immediate need, not only for a second bishop, but for one living in the centre of the country. I was based in the south of the country. The obvious place was Nkhotakota, where Arthur Frazer Sim had in a single year, 1895, built the first school for 100 pupils, baptised the first Christian, a murderer just before being hanged, and died of malaria.

The first African priest – Padre Abdullah – was ordained by Bishop John Hine of Likoma in 1898. In the following year he said that our aim was building up an African Church – not admitting Africans to an English Mission but a “Church of the people of the land.” But he was transferred to Zanzibar after two years, then to Northern Rhodesia and the vision faded.

The Presbyterian Synod of Blantyre of the CCAP (Church of Central Africa Presbyterian) in the south and Livingstonia in the north, had a more consistent picture of African leadership, especially in recent years. At Blantyre, Jonathan Sangaya, partly Ngoni, partly Yao by birth, became General Secretary (virtually bishop) just as I arrived. He was nine years older than me, a teacher who had worked in Ethiopia in World War II and was ordained in 1952. He had had a year’s training for the post in Scotland, and had previously been assistant to an Iona Community General Secretary. In the same headquarters were a number of Scots missionaries, including Tom Colvin – an imaginative hymn-writer and politically aware minister to whom Malawi today owes the Christian Service Committee and other ecumenical initiatives. Jonathan continued in his post until his death in 1979. His enthusiasm and ours were identical and we did much together, including the founding of Chilema Lay Training Centre, the Christian Hospital Association of Malawi (CHAM) and the joint theological college at Zomba.

A bishop in Nkhotakota (a mainly Muslim community) would be virtually on his own, in a town renowned for its political problems. He would have to be tough, capable and imaginative. And able to spend weeks away from home in a part of the country that had few passable roads, where most congregations could be reached only by push-bike or on foot.

My thoughts went back to that seminar in Canada on Roland Allen. Was there a layman in the diocese who already had the vocation and the required training and gifts? I thought of Alec Rubadiri, the first African Assistant District Commissioner, a lay member of the Diocesan Standing Committee, who had gone to spend a year at Exeter University. I wrote to a friend, Jack Dobson, also at Exeter. Yes, the priesthood was something he would think and pray about. Alec wrote later to say, yes, he had made up his mind and was offering himself for the priesthood. Sadly, by the time he returned to Malawi he was already a sick man, but continued reading theology in hospital, where he died in April 1964. I said at his funeral that, “I came to see him in hospital, not so much to give him help as to learn what faith, courage and dedication mean.”

Almost daily I faced the problem: how could I, as an expatriate, new to the country, not knowing a word of the two languages used in the areas where we worked, be midwife to an African Church?

I took the problem to my fellow bishops in the Province, who were in what are now Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana. They were unanimous that it would be right to have a suffragan (assistant) bishop, but only as a stepping-stone to the creation of a new diocese.

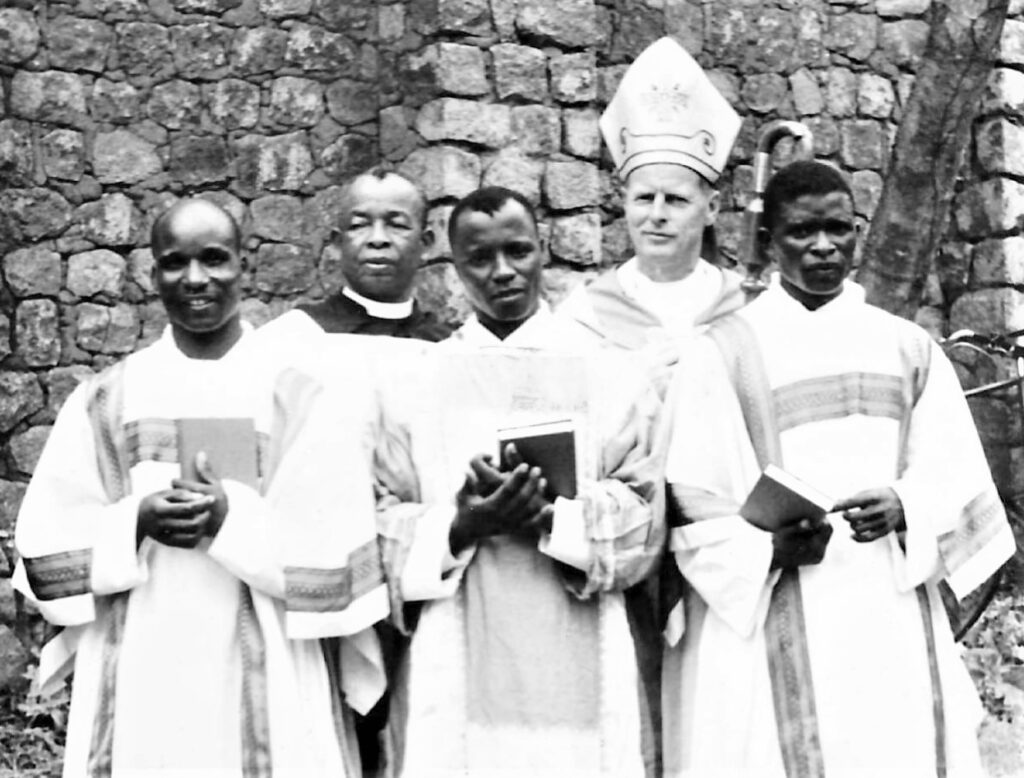

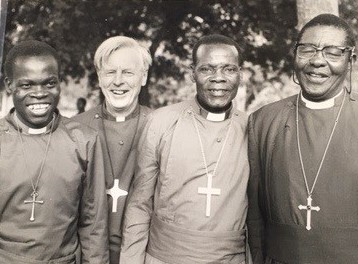

Left to Right: Edward Nanganga, Archdeacon Habil Chipembere, George Mchakama, Nathaniel Aipa

Winds of change

Deciding on future leadership

6 July 1964 was Independence Day, Nyasaland was reborn as a self-governing member of the Commonwealth and renamed Malawi. We had the privilege of attending a dinner with the Duke of Edinburgh and the Governor before proceeding to the newly built Kamuzu Stadium to witness, with thousands of others, the lowering of the Union Jack and raising of the tricolour flag of Malawi – red for the blood that had been shed in the struggle for independence, green for new life and black for Africa, on which was superimposed the rising sun for the dawn of a new life.

The proposal to appoint a Suffragan Bishop was put to our Diocesan Synod in August 1964, seventy members were present and for the first time laity outnumbered clergy. It was also the first time that Catholic and Presbyterian observers attended. The idea was received with enthusiasm. Some wanted two new bishops, some three. Everyone accepted the wishes of the Province that the appointment of a suffragan must be seen as a stepping stone to the creation of a new diocese. Only a few realised the implications – offices, staff, housing, transport and finance.

Other actions of this creative Synod made it possible for the divorced to be readmitted to communion, accepted the new idea of ‘voluntary clergy’ and ensured that there would be women in future synods by giving the Mothers’ Union two seats. We also invited Presbyterians and the Churches of Christ to take part in formal talks about reunion.

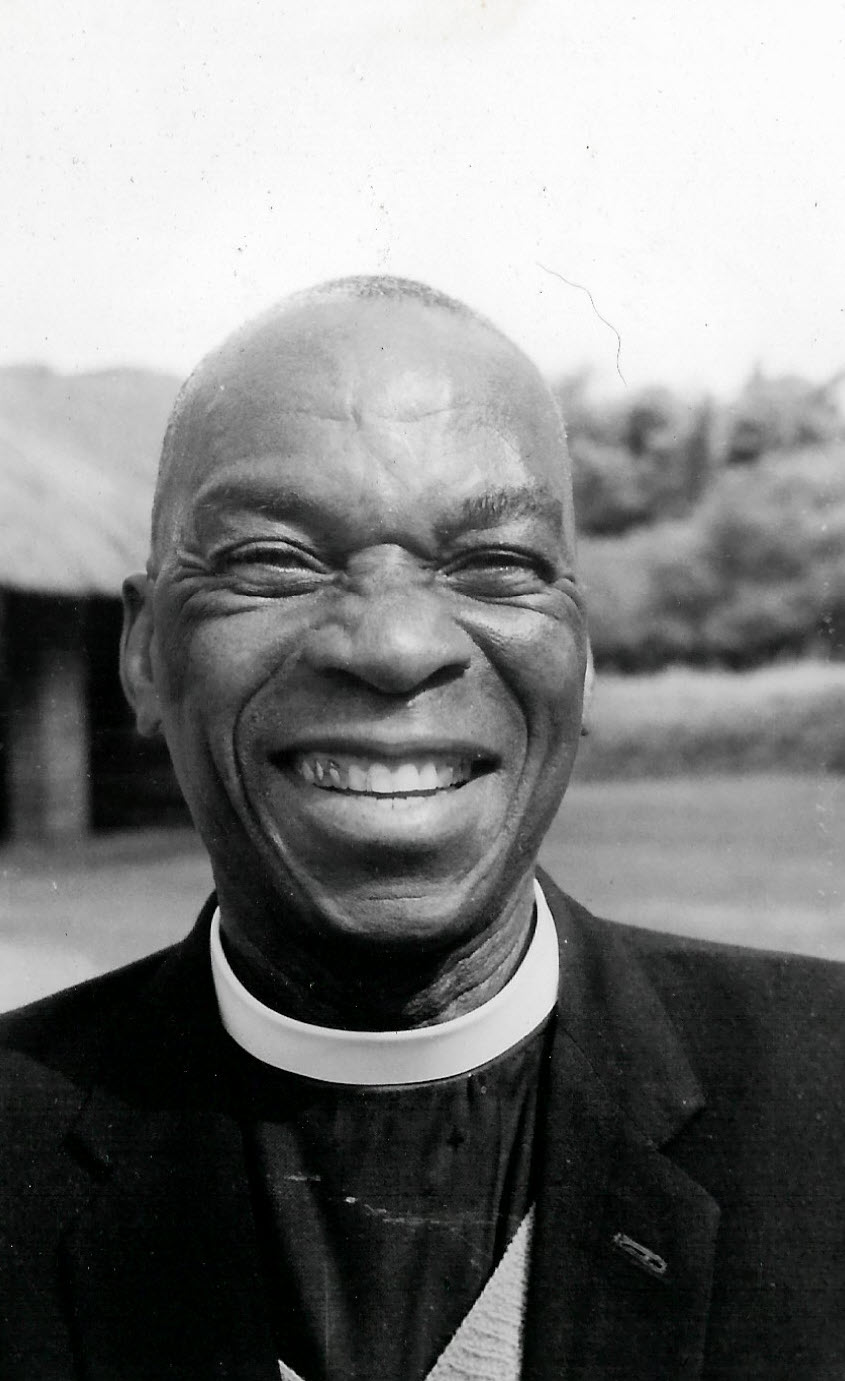

Most people seemed to take it for granted that Habil Chipembere would be the first to be consecrated, followed perhaps by Dunstan Choo, who had been born on Chizumulu Island and was about to be appointed Archdeacon of Likoma. Dunstan had spent a lifetime in the Transvaal as a layman, priest and archdeacon.

The only choice for a bishop among the clergy of the diocese was Habil Chipembere, Archdeacon of Nyasa and based at Malindi. He had been an army chaplain in East Africa and India and a member of the Legislative Council while his son, Henry, was in prison with Kamuzu Banda in Gwelo in Southern Rhodesia. He was loved and respected but already in his sixties and I sensed he was looking forward to retirement rather than pastoral responsibility for the whole of the Northern and Central Regions. Henry had returned to Nyasaland in 1960, but three months later was imprisoned in Zomba, where both Bishop Frank Thorne and I visited him.

It was agreed to appoint a Diocesan Elective Committee with power to nominate a Malawian or other names to the Provincial Elective Assembly for a decision.

Nobody was aware that the day after the Committee met Orton Chirwa would be telling the Governor General that if Dr Banda did not step down as President, all the cabinet would resign.

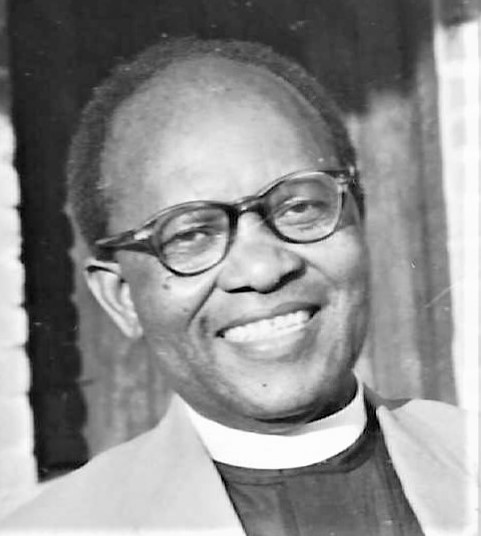

By the time the Committee met again, Habil Chipembere was in exile on Likoma Island, this as a result of his son Henry, a prominent cabinet minister, being part of the opposition to Dr Banda. We met with no clear idea of whom God was pointing to or who should be recommended. Before long the members were unanimous in nominating Josiah Mtekateka to the Provincial Elective Assembly. Josiah was Archdeacon in South West Tanganyika diocese. He had been born on Likoma Island 61 years earlier, but had spent almost all his ministry in Tanzania.

Touring the diocese with the Archbishop

While the political earthquakes of October 1964 were happening in Zomba, I was mostly incommunicado, accompanying our Archbishop on his first visit to Malawi. Apart from brief meetings in Blantyre and my inauguration, no archbishop had visited Malawi since the Province of Central Africa was formed in 1955. Now Oliver Green-Wilkinson had set aside ten days and wanted to see the diocese as it really was. We sailed in ‘Boatie Paul’ – in a previous existence a Dutch canal boat – to Likoma Island where Alban Chilalika, one of the most promising of all our new priests, was to be ordained and Dunstan Choo instituted as the first Malawian Archdeacon of Likoma.

After Likoma we spent a day on Chizumulu Island, ten miles to the west of Likoma, where Dunstan was born and then sailed the twenty miles across the Lake to visit the congregations on the lakeshore south of Nkhata Bay. At dawn, as we landed at the little village of Kapando, a message came that the local leaders of the Presbyterian Livingstonia Synod would like to visit us. Our surprise was great when after lunch there arrived, not just the local leaders but four ministers and forty church elders from fifty miles around. An impromptu meeting was held under a great tree.

The UMCA history records that “In the early part of 1881, Mr Johnson sought help from the Scottish Mission station at Livingstonia. His hands were ulcerated, and these good Samaritans nursed him and sent him away well.” I said that we had been working alongside each other for two-thirds of a century, yet we had hardly ever worshipped together or made any attempt to plan jointly how the gospel could take root in the North. Oliver and I thanked them most sincerely for taking the initiative to meet with us. It was a good meeting and we agreed we would work together more closely in the future.

We then sailed south. Disaster struck after sixty miles as we approached Liwaladzi. A passenger from Likoma said he knew the coast well and the sandbanks had shifted. We should head straight for the village, not up the small inlet. The crew took his advice – and then, a hundred yards from the shore, we ground into the sand, jamming the propeller and buckling the rudder. The reception party of church elders stripped off their clothes, waded out to us and carried Oliver ashore to the cheering crowd awaiting us. After this we walked about ten miles to the Bua river, crossed by canoe and then continued by car to Nkhotakota.

This all happened on the day that – 250 miles further south – the government finally broke up, with four ministers sacked by Banda and three more resigning. All left the country.

We went through Nkhotakota and on to Sani, 6 miles south. This had been the village where Leonard Kamungu began his brief work as the first African priest in Malawi. He was ordained in Likoma Cathedral on 18 April 1909 and posted to Sani. There was an old man who still remembered the fire of his sermons and the sadness they felt at his early death. He had volunteered to go with a small group to Northern Rhodesia.

They reached Msoro on 8 January 1911; in May 1912, twenty-four Wakunda people were baptised, “The first fruits of my work,” Leonard said. On 27 February 1913, he died. It was thought that he had been poisoned by the chief, afraid that these Christians might steal his authority. What I knew for certain is that fifty-one years later I met this old man whose faith was still sustained by his vivid memories of Leonard Kamungu.

I reached home for a relatively quiet ten days. For five months we had been without a diocesan secretary or treasurer, so there was no shortage of letters to be answered and account books to be made good. But reinforcements were on the way and one week later we received Laurence Lees to be the new head of Malosa Secondary School, bringing skills learned in Pakistan. Jeff Schiffmayer, whom I had met as a student at Nashotah House seminary in Illinois in temperatures of thirty-four degrees below zero, and David Hammond from Texas, to be both secretary and treasurer.

A week later a youth gang – for no obvious reason – burned down the girls’ dormitory and two houses at St Michael’s Teacher Training College at Malindi, presumably because Anglicans were perceived as being too friendly to Henry Chipembere, son of the Archdeacon, who was hiding in the hills behind Malindi.

Senior leadership

New Archdeacons for Likoma and Ntchisi

Habil Chipembere had been the only African amongst the four archdeacons. Now he was gone, never to return. At village level pastoral care depended largely on teachers, trained not only to teach but also to take charge of one or more village congregations. They preached on Sunday, took classes for the young, prayed with the sick and buried the dead. The priest, who had no transport, might appear every two months, as he had ten to twenty ‘out-stations’ to look after.

With independence, the system collapsed like a pack of cards. Teachers became employees of the government and looking after a church was no part of their contract. There was an urgent need for archdeacons who could train clergy, new and old, to operate in a changed environment. We prayed for a solution, but none was in sight.

Then two unexpected letters arrived – answers to our prayers. One came from a priest I had known in the 1940s in Pretoria, Dunstan Choo. Born on Chizumulu Island, seven miles west of Likoma and a quarter of its size, he had worked on the Northern Transvaal mines as a layman and was ordained in Pretoria in 1946, when we first met and now was an archdeacon.

Dunstan’s letter said he wanted to give the last year of his priesthood to God in the land of his birth. I wrote back to say we should be delighted to have him as the first mainland priest of the Northern Region but pointed out the snags: a salary one-fifth of what he earned in Pretoria; a push-bike instead of a car in a mountainous region the size of Wales; no more than a token pension and no assistant priest for at least two years.

He wrote back simply, “I have prayed about this and am coming.” He began work in February 1963 at Chilambwe, near Nkhata Bay where there was a small congregation. He also had the care of Mzuzu, with a more embryonic group, and a few house-churches that appeared and disappeared as civil servants were moved around.

Dunstan did a magnificent job as the first Anglican priest ever to live on the mainland of the Northern Province. He also opened a clinic in his kitchen, later staffed by his daughter Joyce Nyirenda, a trained nurse. Forty-two years later, Chilambwe Health Centre still serves the fishing people south of Nkhata Bay.

Six months later I was able to report:

Fr Choo’s churchwarden at Nkhata Bay is paying his bus-fares when he travels. He is also paying for work to be done on the church, and finding from his own income, £1 a month for catechists wherever his priest may require them.

I was delighted when the Diocesan Standing Committee approved my suggestions that Dunstan should be the new Archdeacon of Likoma, when Gerald Hadow moved to South West Tanganyika in October 1964.

The second letter was from Sheldon Jalasi, whose story was parallel to that of Dunstan. He came from Likoma Island, trained as a teacher and then went to work in Northern Rhodesia, where he was ordained and worked on the Copperbelt and in Lusaka. There he was made a canon and given an MBE. He too wanted to serve his final years in the land of his birth. He became Archdeacon of Nkhotakota, which had become vacant when Guy Carleton left for the Caribbean.

The job was challenging Fr. Oswald Chisa, the priest-in-charge, was a sick man and retired shortly afterwards. On a recent visit I had been met on arrival by the new MP, who called me into an office and said, “I just wanted to tell you that if you do or say anything that might affect my political standing in Nkhotakota, you mustn’t be surprised if you find your students midwives’ hostel is in flames.”

This didn’t seem to worry Sheldon and in July 1964 I was able to induct him as Archdeacon. Cyprian Liwewe, who had just succeeded Oswald Chisa as priest-in-charge wrote:

The Church of All Saints was filled to capacity, with some outside. People were gathered beneath the great fig-tree under which Dr David Livingstone sat a century ago. Under this same old tree the new Archdeacon blessed his people.

In 1965 the Diocesan Standing Committee created a new Archdeaconry of Ntchisi, covering all the Central Region, except for the lakeshore strip. The gospel was first preached here in 1907 by Petro Kilekwa and nurtured by him as teacher, deacon and priest for the next fifteen years. It was the fastest growing area in Malawi. I had confirmed three-hundred at Madanjala on my first visit. Jane drew the plans for the first house we had ever had that was designed for a married archdeacon. When she and I sat in the house in 2005 it had no cracks or termites to show for its forty years.

Sheldon often travelled with Bishop Josiah and together they took far-reaching decisions. Dancing Nyau was a traditional custom among the Achewa of the Ntchisi area. Most missionaries frowned on it as a symptom of heathenism. Josiah writes of a visit to Malomo, where the priest was Dunstan Ainani, who in 1981 followed me as Bishop in Southern Malawi:

Fr Ainani tells me these people are regarded as heathens because they were Nyau dancers. He told them there was nothing wrong in Nyau. After a long and fruitful discussion, they asked if they could become Christians. Malomo people are very happy and ready to make bricks for their priest’s house.

With no Anglican teacher training college in the Central Region, ecumenical relations were vital. I was delighted to receive a letter from an Anglican student at the Catholic St John Bosco college at Champira saying:

For the many years since this College started, no Anglican priest or layman has ever visited us. On 13 June both Archdeacon Jalasi and Fr James Lunda came. Both the Chaplain and the Principal paid tribute to the priests who have come this month, including Fr Lloyd Chikoko, who came seventy miles on foot from his parish of Dwambazi.

After five years in Ntchisi, Sheldon returned to Chipata, in Zambia, just across the border. Bishop Josiah wrote of him, “He did very excellent work in Ntchisi. All Secondary Schools and Young Pioneers of Ntchisi and Dowa Districts miss his pastoral care and cheerfulness.” The churchwarden at Chipata was more concise, “He bounces round like a rubber ball.”

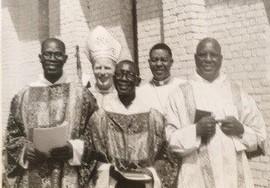

Left to Right: Yonathan Chambombe, Michael Kamaliza, Robert Chikoma, Josiah Mteketeka preached

Searching for a suffragan bishop

On 6 December 1964 the Diocesan Elective Committee unanimously nominated Josiah as suffragan bishop. Clearly intending that he should become bishop of a new diocese as soon as funds could be found for buildings and staff. I wrote to Josiah at once. He took my letter to Bishop John Poole-Hughes who then told him for the first time that the clergy of SW Tanganyika had told him they too wanted Josiah as their suffragan bishop. “Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked. “I was asking the government. As you are not a citizen of Tanzania I was afraid you might not be acceptable.” Josiah agreed to go into retreat for three days of prayer. He then made up his mind – it would be Malawi. Bishop John was genuinely sorry and gave him the cross and ring he had bought for him. Joseph Mlele became suffragan of SW Tanganyika three months after Josiah’s consecration.

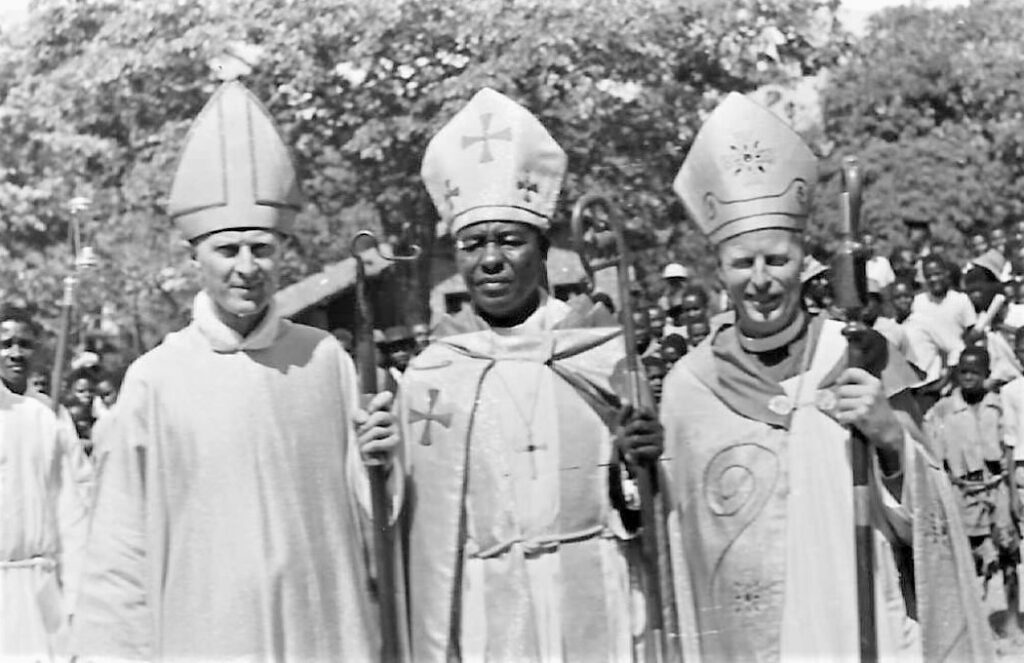

On 27 May 1965, Ascension Day, Josiah Mtekateka was consecrated bishop in Likoma Cathedral before a congregation of 5,000 inside and outside the building. Those present included two Catholic bishops from the regions where Josiah would be working, Jobidon of Mzuzu and Fady of Lilongwe, both French; the heads of three Presbyterian synods; Sir Glyn Jones, the Governor General, bishops from the Province headed by Archbishop Oliver Green-Wilkinson. Bishop Frank Thorne had come from Tanzania to take Josiah’s retreat. The address at the consecration was given by Cecil Alderson, Bishop of Mashonaland in Southern Rhodesia. He spoke in Chinyanja, though he had probably hardly heard a word of the language in the thirty years that had gone by since he was briefly a missionary on Likoma Island in the early 1930s.

Archbishop Oliver Green Wilkinson, Bishop Josiah Mtekateka, Bishop Donald Arden

Josiah stayed three months with us, based at Malosa. He and I spent over a month visiting every parish in his area in the Central and Northern Regions. Often we shared a confirmation together, each of us confirming thirty or forty candidates. So many goats were given to Josiah that we had to set up sub-stations for them, goat-pens where they could find bed and breakfast till Josiah could collect them.

While Bishop Josiah and I were away at Lambeth for four months in 1968, the Diocese, for the first time, was cared for by a Malawian Vicar General, Mathias Msekawanthu. And Malosa Secondary School, our next-door neighbour, now had a Malawian head, Frank Mkomawanthu, one of our candidates for the voluntary ministry. But there was still far to go before Bishop Hines’ 75-year old dream of a wholly African-led diocese was to come true.

Learning Chichewa

I began a course to learn Chichewa at the Roman Catholic White Fathers’ language school in Lilongwe. Speaking Chichewa was one of the conditions set when I was elected in 1961. The real reason is to avoid the patronising eye of Basil, now five and a half, when I have to ask him to translate for me. It’s a little like being back at my theological college at Mirfield. But there are considerable differences.

It is co-educational – eleven fathers or brothers and nine sisters. Eight nationalities are represented. A fellow student, who has just looked in to repair a lock as I write, tells me he began life in Poland, continued at seven in a concentration camp in Siberia, did his schooling in Tanzania and trained as an electrician in England.

We are definitely post-Vatican II. At Sunday lunch this morning the little Breton father, who is bursar, appeared in a clerical collar. This caused an outburst of applause and cries of, “Have a good leave, father!” Some of our more conservative Anglican clergy would have been surprised to see the co-celebrant accompanying the Kyrie at Mass on an African drum, or the nun at the south end of the altar playing spirituals on a guitar.

The 1968 Provincial synod held at Marendellas (now Marondera), was lively and encouraging, with a genuine African feel about it. A tense moment in a debate about whether the Province could continue in view of the political tensions between Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambia, was relieved when one of the African laymen said, “I came here fearing apartheid but I find myself sleeping in the same room as the white Dean of Bulawayo.”

In a letter I wrote to my brother Felix relating to Africanisation

I feel like a stranded whale, left on the beach by the outgoing Colonial tide. In independent Africa I shall soon be the only white Bishop other than in Northern Uganda

Archdeaconry Councils

Early in 1966 the Diocesan Standing Committee (DSC) gave flesh to a proposal from the Pastoral Committee that we should set up Archdeaconry Councils. The idea appealed to me as the cost and travelling time in the 1960s of bringing clergy and lay people 400 miles from the north to attend synods meant these could be held only at two-year intervals. This was far too rarely to support lonely people doing a lonely job. The DSC listed for guidance some of the special areas where Archdeaconry Councils could help, such as circulating literature, stewardship, the training and deployment of Lay Leaders, co-operation with other Churches and election of a representative to the DSC.

The success of the first two that I attended convinced me that this was the way forward. All the clergy were involved together with a number of lay people. I was astonished at the range of issues raised: the work of Elders, church gardens as a means of self-support, polygamy, Sunday Schools, the ordination of catechists after a one-year course at Chilema, the proposed new People’s Prayer Book, outreach to Islam ………

More and more I wondered if dioceses should be the size of archdeaconries, instead of the vast units we had inherited. When Frank Thorne became Bishop of Nyasaland in 1936 the diocese included the present dioceses of Ruvuma, S.W.Tanganyika, Niassa (in Mozambique), Eastern Zambia and the present Malawi, with seven languages were used for the liturgy. In the early Church, a diocese was just a single city and the villages that surrounded it. It is sad that today’s structures often result in the setting up of a diocesan administration that is so financially demanding.

Anglican Council of Malawi

Beginnings

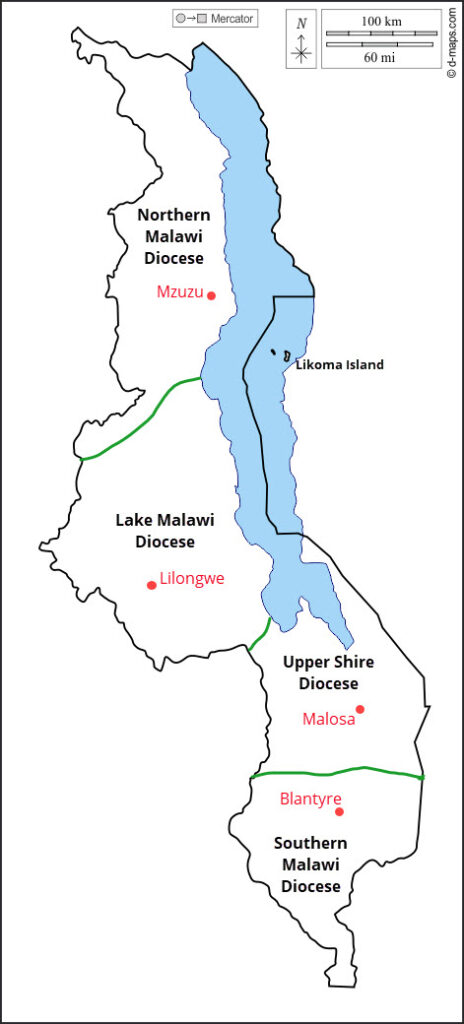

ACM was created in 1972 following the division of Malawi into two dioceses, with Josiah Mtekateka bishop of the new diocese of Lake Malawi and I bishop of the new diocese of Southern Malawi.

Unlike the Zambian Anglican Council, ACM had very few teeth to it. It controlled the Pension and Provident Funds, and various other trust funds. If money was given for the building of a particular hospital or school and it was not possible to begin work immediately, the trustees safeguarded the money. The trustees were registered under Malawi’s Incorporation Act and became the legal owners of all church land.

Purpose

Its purpose was best summed up in the first object of its constitution:

“To undertake on behalf of the two dioceses, and with the authority of their respective synods, such work as can only be done together, or can best be done together.”

Training of ordinands

ACM looked after the training of ordinands. Seven years could elapse between the time an ordinand was chosen and the time he was ordained. After such a long time-gap no one could say which diocese would be in most need of a priest. All ordinands were therefore trained under the umbrella of ACM who then decided to send them to the dioceses in proportion to their needs.

Publishing

Since it would be expensive and confusing to have different prayerbooks used in different parts of Malawi, it was the job of ACM to look after publishing.

Consultative

Apart from these functions ACM was a consultative body which meant it was a place where representatives from the two dioceses could exchange views and reach agreement. It had no power to compel either diocese to do anything, including no power over the annual budget of each diocese.

Officers

In order not to waste money, each diocese sent only its bishop, an elected priest, an elected layman and its diocesan secretary. A ninth man was to be chosen jointly to avoid a deadlock. The first elected office holders were:

Chairman – Revd Douglas Yeppe (DSM)

Secretary – Miss Doreen White (DLM)

Treasurer – Mr Wesley Mauwa (DSM)

Minutes were sent to all members of both Diocesan Standing Committees.

Creation of the Diocese of Lake Malawi

Josiah was 62 when he became Bishop and I did not expect him to be able to cope with this demanding job for more than a few years. In the huge area for which he was responsible there were no tarred roads, other than a couple of streets in old Lilongwe and a mile or so in Mzuzu, built to take Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, from the airstrip to her house for the night. From Nkhotakota, where Josiah was based, if you headed south, you would inevitably meet a washed-away bridge; if you went north, you came to the Bua river with only a canoe for crossing. If you went west, you met a mudslide in the rainy season. And east was the Lake, where, after boatie Paul was wrecked, there was only Ilala going north one week and south the other. The Bishop’s house was a elderly house and the diocesan headquarters a block of three small rooms, now used as the primary school office.

Things improved in 1971 when the Diocese of Lake Malawi was formed and got a little better over the years as funds arrived from Texas. With no complaints and huge courage, Josiah kept up a vibrant ministry until Peter Nyanja succeeded him over thirteen years later.

At the end of 1971 I wrote:

The new Diocese of Lake Malawi, incorporating the Northern and Central Regions, goes ahead steadily but Bishop Josiah has no chaplain and no graduate priest in his diocese. At the age of sixty-seven he continues to cover great distances on foot and is now preparing to take on the nightmare of running a diocese with more work, as measured by confirmations, adult baptisms, schools and health centres, than I faced in 1961, with a fraction of the skilled staff I inherited.

Editors: see other chapter for more detail on the life and work of Bishop Josiah

Malawi traditional religion

I found little in traditional religion that was incompatible with Christianity. I was encouraged by the African Ecclesiastical Review (AFER), an East African Catholic periodical to which Adrian Hastings contributed and which often reported the imaginative use of traditional music and dance.

No African language with which I am familiar even has a word for ‘religion’. The existence of a supreme Being is normal, at least in Southern and Central Africa. There are customs, such as polygamy, that all churches reject, though many churches would – correctly in my view – say that a polygamist being baptized as a Christian, would be right to keep a second or third wife, if the only alternative for her would be destitution. The current tension about homosexuality shows how difficult it is, even for Western Christians, to balance traditional attitudes with modern psychology.

The closest parallel is the difference between the Old and New Testament ethics. There we have guidance from Jesus, himself for example. “You have heard it was said by men of old times … but I say to you …” The African Church still has the Spirit to guide it. I see Africa’s traditional religion as their Old Testament – full of positive ethics, but as Jesus showed, to be used with discretion.

Music

My father tried but with limited success to transfer his love of music to me. The attraction of South Australian sunshine proved too strong and I got no further than my one composition, ‘The March of the Tin Soldiers’ In Pretoria I did my best with the bass part of hymns because South Africa has a strong musical tradition and every adult male is expected to sing tenor or bass. If there was a blackboard in a classroom, a quarter of it would be taken up by the hymn of the week in tonic sol-fa. Unexpectedly, because the Anglican Church in Malawi had, at that time, no strong musical tradition, African music became one of our first footsteps towards becoming an African Church.

Mindolo

The All Africa Conference of ‘Churches in April 1963 high-lighted the need for African church music. As a result, Mindolo Ecumenical Centre on the Zambia copper belt announced a month’s course in developing African liturgical music. Victor Chunga, who taught in Chididi school, south of Nkhotakota, applied and represented us. In the 1890s the Synod of Livingstonia CCAP had developed African church music to a high degree, by adapting traditional music for use in church and by encouraging African composers. This reflected their Angoni links with Zululand and the foresight of the first Scottish missionaries. These tunes had spread to other CCAP synods and to other churches through funerals.

Victor Chunga wrote delightedly from Mindolo of his first exposure to an ecumenical gathering:

Central Africa is being born afresh with mutual racial understanding. The Holy Ghost is really working in people’s minds to reach the goal-post of religious reunion. Christian friends, regardless of the churches they come from, have come to find out methods of improving African church music.

Victor spoke to our next diocesan synod and told us how he had been asking elderly people to sing their old tunes to him so that he could find suitable words to fit the tune. Christians, he said, should not despise their cultural inheritance.

In 1964, Victor took Maxwell Maputwa, a fellow teacher, with him to another Music Workshop at Mindolo. They told Ecclesia:

We have been working on the tunes originally collected by Canon Hicks at Nkope for the new diocesan hymnbook. These can be arranged and harmonised in tonic-sol-fa.

Missa Malawi

Our setting for the mass, using African tunes, has so impressed the music director and other members of the course, that part of it were performed at Luanshya Church. This will be known as ‘Missa Malawi’.

A lay member of Chombo church responded:

How impressive it was to hear ‘Missa Malawi’ sung in our church! Young children sang as if they were singing their own traditional songs. We should all co-operate with Mr Chunga and invite him to our parishes.

Victor Chunga wrote in Ecclesia:

As I looked at the leaves of a mango tree, I noticed each one was different. The same is true of human beings. New experiences happen in every generation: the Church grows in changing. Music is one of the chief ways of expressing our feelings. Researching African music is hard and needs a lot of people to help with suggestions and criticisms.

George Merikebu, joined the debate:

Psalm 150 says, ‘Praise him with the trumpet: praise him upon the harp.’ This answers my long wrong belief that to play an instrument in church is against God. So why not drums?’

Chilema

Richard Baxter of the Iona Community and a minister of Blantyre Synod CCAP, a lover of Malawi music, became the first warden of Chilema ecumenical lay training centre. In 1966 he announced an international music workshop.

Kungoni Centre of Culture

Twenty miles from us a young Canadian White Father called Claude Boucher, was doing creative things in liturgy. John Leake, the priest who was looking after the imaginative Anglican programme at the Chilema

Ecumenical Lay Training Centre, invited me to go with him to Claude’s parish centre north of Balaka for the pre-Christmas mass for his outstations. It was a revelation – Malawian music, liturgical dance, drums – the lot. I praised it in Ecclesia and sent Claude a copy.

He asked me in return to write to his African bishop, who was angry with him and had threatened to expel him. His bishop relented, but a few months later changed his mind and sent him back to Canada. I am glad to say that Claude was invited back a few years later by another diocese and founded the Kungoni Centre of Culture and Art at Mua, where he still works. Mua is famous within Malawi and internationally for its imaginative carvings, often by young men with little formal education.

By 1970 even tiny congregations would have their own youth choir. The resistance to drums lingered in larger and older congregations. We were delighted to hear the magnificent drumming in Likoma Cathedral itself during its centenary in 2005.

Liturgy

A brief visit to Liuli Cathedral in South-West Tanzania in 1962 opened my eyes. This was the people of God celebrating the eucharist together, not a priest ‘saying Mass’. The altar had been moved from the remote end of the chancel to be just in front of the people and the celebrant faced them. Worship seemed to have come alive. In a large building packed with people I could hear every word from my place at the back. The Spirit of the Second Vatican Council seemed to have reached the Anglican Church in this remote corner of Africa, even thought the Council had not yet met.

Liturgically, in Nyasaland, we were still in the doldrums. The printing press on Likoma Island, that had done wonderful work for over eighty years, was closing down and could never be reopened, partly because we could not afford it, partly because a press on a remote island could never expect the flow of commercial orders needed to keep skilled staff busy. Its method of typesetting – letters picked out of hundreds of little boxes with a pair of tweezers – belonged to the age of Caxton. It had a glorious past and had produced tens of thousands of prayer-books, hymnbooks, school readers, catechisms, and guides to marriage in two editions. The green edition was for the Mothers’ Union in general, the red edition was given to brides only, a few days before their wedding. All in four or five different languages. But it had no future.

Provincial comments

The Province expected us to abandon the rather fine UMCA liturgy for the eucharist and change to the old and uninspired South African form. This meant our vibrant and relevant liturgy would have to go. Instead of prayer for the rich to share with the poor; and for Jesus, who was a refugee in Egypt to be with our migrant workers in the Rand gold-mines; and for the Jesus who questioned the teachers in the Temple to give wisdom to our teachers – we were expected to go back to the long and boring Prayer for the Church Militant here on earth. It seemed to me a case of ‘Backward, Christian soldiers….’

There were also problems of language. Likoma Island spoke the Nyanja of Mozambique. This was perhaps as different from the standard Nyanja of Nyasaland as Robbie Burns’s Scots is from standard English. This in itself was no problems to Africans who are born linguists. Children of six or seven at Broederstroon, which I used to visit once a month in the 1940s, spoke their own language, Ndebele, which they brought with them when they arrived from Matabeleland in the 1650s; Tswana, which everyone around them spoke; English and Afrikaans, the two official languages; and Zulu, in which I read the services. However, they had trouble in understanding the Xhosa-speaking headmaster I appointed. Xhosa-speakers, certainly in the 1940s, had a strong linguistic loyalty and tended to take it for granted that others would understand their language.

Chilikoma

The problem was that ‘Chilikoma’ – as other Malawians called it, the language of Likoma Island – had imported many Swahili theological words. Swahili is not a true Bantu language. It grew up over a thousand or more years as a means of communication with Africans of many different tongues along the 1,500 miles of Indian Ocean coastline between Mozambique and Somaliland. Its grammatical framework is Bantu, but 25% of its vocabulary is Arabic. Malawi had few contacts with Arabs, apart from slave-traders, and has never used Swahili. UMCA missionaries inherited a tradition based on Zanzibar Island and its Swahili speakers. Thus a number of strange Arabic words had become UMCA-speak for key theological words – Mtakatifu for ‘Holy Spirit’, mazabau for ‘altar’ and many more.

This gave UMCA a foreign flavour and was a serious barrier to evangelism. When I first went to Salima, on the western lakeshore, to take a confirmation, I had problems in finding the church. Nobody had ever heard of an Anglican church. I tried ‘UMCA’, ‘Church of England’, pretended to put on a mitre … no response. Half a dozen went into committee and then came out beaming – “Is it the Church of Likoma?” Yes, they all knew that, a quarter of a mile out of town. Even in Soche, the first new urban township in Blantyre, 400 miles from Likoma, the congregation was mostly made up of Likomans who could understand the language.

One spark of hope was at Nkhotakota where Fr Oswald Chisa and Archdeacon Guy Carleton had battled with the ‘Chilikoma’ problem. Working together they had published a hymn-book in standard Nyanja/Chewa. Oswald Chisa had been detained before my arrival for being over zealous in the cause of independence but subsequently released as he was far from fit.

People’s Prayer Book

On a hot afternoon at Mponda’s in January 1966, the People’s Prayer Book and hymnbook was conceived. I noted in Ecclesia that the previous prayerbook had sold 3000 copies in ten years, and that in those ten years, 20,000 people had been confirmed. Few of them would ever see in print the promises they had made at their confirmation or their wedding.

The problems were many and acute. Did we submit to the Province and accept the Provincial Prayerbook? Could we ask our people to buy a book that would cost a month’s earnings or a quarter of their harvest? How could we escape from the English and German hymn tunes droned out at a snail’s pace in most churches? How could we bring to life the many saints whose lives we celebrated but about whom we knew very little? Which of the frequently changing spelling systems for Chichewa should we use.

Eventually decisions were made. We could select ruthlessly and put into the hands of the people the minimum number for worship. The hymns would have printed tunes, even though few except those who had worked in South Africa knew tonic sol-fa. Then perhaps Anglicans might learn to sing as well as Presbyterians. We would also print some of the lively Malawian tunes that set the whole church echoing. We would borrow from Livingstonia some of their magnificent Tumbuka tunes. We would choose only the best bits from thirty-one psalms so that laypeople who did not have time for the daily prayers could use one on each day of the month. Each psalm would have its key thought printed as an antiphon to be said or sung after each verse. Even those who had not been to school or whose eyesight had failed, could join in.

Gradually the book grew. A manuscript was presented to synod. They didn’t like it and sent the Liturgical Committee on a round of archdeaconry conferences. Agreement was reached and in 1968 we were ready to print when all kinds of setbacks appeared. Devaluation of the Kwacha upset the estimates. Nkhoma Press had to buy new type to set the sol-fa on their linotype machines. Twice the approved spelling of Chichewa was changed. The printer went on long leave.

Mapemphero

At last, in August 1971, Ecclesia was able to announce:

MAPEMPHERO NDI YIMBO ZA EKELZIA is now published! 12,000 copies have been printed. As soon as they are sold, the revolving fund can produce an edition in ChiYao.

In addition to the services found in prayerbooks throughout the world and thirty-one psalms, Maphemphero also included features which in 1971 were still unusual, such as Sunday readings on a two-year cycle, obviating the need for circulating to all lay leaders the readings for the year, thirty-one canticles, again with a chorus and a congregational Service of Penitence, services for baptism and confirmation, marriage, burial and compline.

Also included were a brief biographies of each of the forty-four saints commemorated, including many African saints and martyrs – to name only the local ones: David Livingstone and Bishop Charles Mackenzie, who led the way; Fr Arthur Fraser Sim who baptised the first Christian in Nkhotakota on the lakeshore, opened the first school and died there in 1886 all within a year; Leonard Kamungu, the Malawian priest who died, perhaps as a martyr, a few months after being the first to bring the gospel to Zambia; Bernard Mizeki, born in Mozambique, attended a Christian school in Cape Town, became a catechist in Mashonaland (Zimbabwe), martyred for his faith; and William Percival Johnson, the founder of all the seven dioceses that border Lake Malawi.

Islam

Yao-speakers in Malawi are approximately 10% of the population and most of them are Muslims. The two main Muslim centres are Nkhotakota, a port on the western lakeshore in the Central Region with a population of 30,000 and the southern Lakeshore where Chief Mponda was the senior Yao Chief in Malawi. His court was within 200 yards of the mission station. Many of the children at our school would go on to the Quran school where they would read in Arabic with a Muslim teacher. The only priest in Nyasaland who could meet these requirements (apart from a handful of recently ordained) was Petro Kilekwa. But he had retired 12 years before I came on the scene (see Appendix).

I wrote to my contacts in Nairobi and was delighted to hear of a short course being run in Mombasa in 1966 by the Christian Council of Kenya, who offered us two places. I consulted with Bishop Josiah on whom to send, and he at once said, “Me and Joseph Chikokota”, naming a young priest from Malindi, where the congregation was really a group of Christians who had migrated from Likoma Island (such as the Chipemberes) in a totally Islamic area.

The Mombasa course was a great success and both came back full of new things they had learned. Josiah wrote in Ecclesia:

None of us had visited a mosque before. The people praying made different actions during their prayers, kneeling and prostrating their faces and noses onto the mat, repeating likewise three times. Then they pointed one finger indicating they believe in one God only. Then they looked right and left, showing they wished God’s blessings to their fellow Muslims. Then all stood and prayed together with hands raised. When they had finished they sat around in classes learning their Laws. That day the Sheikh was teaching his students about the dividing of dead people’s property. All the teaching came from the Quran.

It was a very interesting visit for us. We saw many boys who came to worship. This to me is a challenge. Our Christian boys do not take part in worship during the week, only on Sundays.

A few months later, John Liomba, who was teaching at Msusa, in Joseph Chikokota’s parish, a wholly Muslim area in the hills behind Malindi, reported:

Thirty-six catechumens, male and female, big and small, were baptised by the Revd Joseph Chikokota. It was interesting to observe the age contrasts. The youngest boy was Wilfred, aged 8, the oldest lady, Beatrice, in her late 70s. The priest and his servers walked side by side with the Godparents to and from the New Jordan brook, half a mile from the church. If all adult baptisms were done this way, none would have a wrong picture of the tremendous work of St John the Baptist.

It was impossible to resist Joseph when he came to ask if he could accept the offer of a place on a nine-month course on Islam in Nigeria. We all learned from his Question and Answer articles in Ecclesia.

A few years later I receive a letter from Douglas Yeppe, one of our younger priests, saying:

In December 1972 I was invited by a Muslim teacher to attend their mosque on Friday. I accepted their invitation, washed my hands and feet and dressed myself like a Muslim. I was then asked to preach a short sermon, which I did. Again on 26 May, Dennis Kalino, Catechist Madota and myself were invited to the Islamic festival of Siyalah. I was also asked to preach. I was amazed to see the Sheikh emphasising his sermons by quoting Christ’s teachings.

By the time I left Malawi in January 1981, Peter Njanja was Bishop of Diocese of Lake Malawi and Dunstan Ainani had succeeded me as Bishop of Southern Malawi.

Bishops Peter Nyanja, Donald Arden, Dunstan Ainani, Josiah Mtekateka (1980)

Postscript

There are now four dioceses in Malawi

Diocese of Lake Malawi (1971) – Diocese of Northern Malawi (1996) – Diocese of Southern Malawi (2002) – Diocese of Upper Shire (2002).