I was born, to my dismay, at Boscombe, on the edge of Bournemouth. I say Boscombe, not Bournemouth because it sounds less dull. My brothers were born in more colourful places, Felix in Penang, Mike in Tebin Tinggi, Deli, Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies. Mike had a birth certificate in Dutch of which I was very jealous.

The reason for being born in Boscombe was that Dad caught a tropical bug, which was not identified until some fifty years later. It may well have been Hong Kong encephalitis B, a slow-acting tropical coronavirus resulting in a horrendously high temperature.

Family History

The Cheshire Ardens from which Donald was descended were traced by Felix in a burst of genealogical interest in the 1990s. They belonged originally to the Ardens of Warwickshire, Staffordshire and the Forest of Arden, one of only four families in England whose roots can be traced back with certainty to Saxon times.

Arden was the name of the great forest of Warwickshire and is of Celtic origin, meaning “well wooded.” The main branch of the Ardens have always been based in Warwickshire, but somewhere before 1229, John de Arden, son of Eustace de Arden, was “named as his knight by Ranulph III, Earl of Chester” and had a grant of Aldford Fee, in Cheshire. There the family split into two halves, the western half being associated with Alvanley and Aldford, near Chester, the eastern half with Stockport, spreading over to the edge of Derbyshire.

Felix traced Dad’s ancestry back to a William Arden of Norbury, born at Disley, 6 miles south-east of Stockport and close to the Derbyshire border, on 30 March 1728. From then on the family lived at a small yeoman farmhouse there, known rather grandly as Stanley Hall. (Google Map) This has been beautifully preserved and is now lived in by the green keeper at Disley golf course. Jane and I sought it out and photographed it in the 1980s. The base of the main branch of the Ardens however remained in Staffordshire and Warwickshire. It was a Mary Arden from Stratford-upon-Avon who gave birth to William Shakespeare.

My Parents

My dad Stanley Arden was born in Heaton Norris (Google Map) on 24 September 1874 and given the name of Stanley. His father, who was also called Stanley, was a law clerk of Cheadle Heath and a member of the Hallé Choir. Heaton Norris has long since been absorbed by Stockport but the lovely half-timbered Underbank Hall (Map), the town house of the Cheshire Ardens, still stands in all its glory and is owned by the Natwest Bank. Their Arden’s country house, Harden Hall, is a ruin on the edge of Stockport. Dad was a choirboy at Cheadle Hulme and had a great love of music. Perhaps the hardest part of his disability was that it prevented him from playing the piano. He tried to teach me without lasting success, despite my having composed “The March of the Tin Soldiers” when I was ten.

In June 1898 he headed for London and joined Kew Gardens, where he served in the Tropical Department. The last year of his time was spent as a foreman in the Ferneries. At the end of 1900 he was sent out from Kew to Malaya to work on methods of growing and tapping Hevea brasiliensis – the rubber tree. This is a native of the Amazon region. The Spaniards, then the colonial masters of Brazil, had tried by every means to prevent its being planted elsewhere. However, seeds had been smuggled to Kew a number of years earlier and multiplied there. H.N. Ridley had already taken seeds to Malaya a few years earlier and the trees showed every sign of being at home in its rain-forest climate. Coffee was the main crop in Malaya but horticulturalists knew that it could fail at any time through a disease sweeping the tropical world. The message from Ridley and Dad was to plant rubber as shade trees among the coffee. Should the coffee fail, then the rubber would take over. This was exactly what happened.

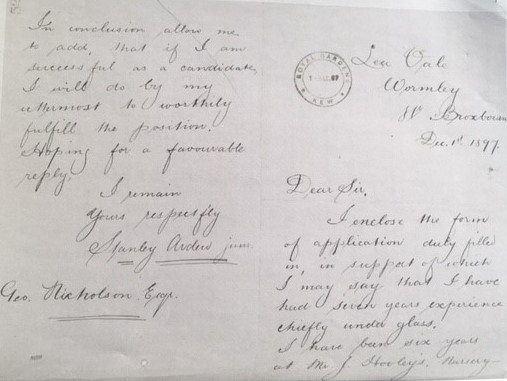

Stanley’s application to work at Kew – 1897

Mum began life in 1880 as Winifred Morland, the descendant of Thomas Morland, born 1729, farmer and inn holder of Ravenstonedale (Map) in the Lune Valley of Cumbria. He migrated to Rotherhithe to work with his brother who had gone there as a shipwright when things were hard in Cumbria and himself became a ship’s carpenter and a Quaker. I am glad that we have northern blood in our veins. When I returned to England from Australia in 1934, I found life in Surrey stifling. The aunt designated to be my guardian was interested only in playing bridge and our relationship came to an end when, playing as her partner at her bridge club, I trumped her ace out of sheer boredom. Even when you escaped to the North Downs, every attractive path seemed to have a notice on it: Trespassers will be prosecuted. But a week or two later when I found that you could escape from the grime and bustle of Leeds to the Yorkshire moors, I felt able to breathe again. Many of my friends at College were fellow-students who had lived in Burma, Africa or Canada or were Yorkshire born.

Mum had also found life in an all-female Victorian household in Surrey stifling and escaped at an early age to train at Charing Cross and Ipswich as a nurse and midwife. She loved telling us of her work as a district nurse in the Land of Green Ginger in Hull, where the policemen would go only out in pairs. At 26, she took off for a nursing post in Singapore Hospital and it was there that Dad and Mum met and were married in Singapore Cathedral. In 2000, Jane and I found some of the likely sites where they would have done their courting and we had a stengah cocktail in the Raffles Hotel in their honour.

South East Asia

Dad’s work with the Colonial Service took them to North Borneo and then to manage a rubber estate in Sumatra, in the Dutch East Indies. Mike was born there on Mum’s birthday in 1909. Felix, always Fee to us, came along a couple of years later when they were managing an estate five hours by launch up the Johore River, just north of Singapore.

All this suddenly changed just after they opened their own rubber plantation – Bintang Estate at Sitiawan (Map) in Lower Perak, about 30 miles southwest of Ipoh. Bintang means “Star with a Tail” and the estate was named after Halley’s comet, which made one of its rare appearances in 1911. Our son Christopher visited what remains of the estate when back-packing around the world in 1985. Mum was in England showing off her first baby to his grandparents when she received a cable saying, “Come urgently. Stanley dying.” Apparently he was in hospital with a temperature of 106ºF, having caught an undiagnosed tropical bug. She had to board a ship at Marseilles and travel for another two weeks not knowing whether she would find him alive or dead. Dad was just 37.

Over the following two years, the slow-acting virus caused him to lose his balance. He remained like that for the rest of his life. He was never paralysed, his speech was unaffected and his mind was perfect until the day he died, but he could walk only if he had something or somebody to hold on to. He used what today we would call a zimmer frame but known to us then as a walking-machine, a heavy wooden thing on castors. For out-of-doors he had a wheelchair operated by two handles with gears. In top gear he did about 6 mph and from age five I chased behind during school holidays. Small wonder that in Swaziland my nickname was Impangeli or Guinea-Fowl. There is a Swazi proverb which says, “Impangeli ikhala igijima – The guinea-fowl cries as it runs.”

Back in England

Boscombe with its hills was no place for a wheel-chair, so when I was three, we all moved to Worthing and stayed there until 1925. They were happy years though I was always jealous of Mike and Fee who lived an exciting life as boarders at St Edward’s School in Oxford. During the holidays they were able to go on long bike rides around Sussex with Mr Pocock who seemed to come from nowhere but was a keen naturalist and took them to Bramber Castle and across the Weald and up the Arun Valley. I learned about these romantic places second-hand from helping Mike develop and print his photos of windswept trees and Saxon churches but I really only got to know Sussex by proxy later on when I found Hilaire Belloc’s poems and books in the school library in Australia.

|

|---|

|

Worthing 1921 |

|

|---|

|

Donald, Mike, Felix and Granny Morland – Worthing 1925 |

Australia Beckons

Mum often begged Dad to take her somewhere where the sun shone. I agreed heartily. Whenever we planned a picnic on the prehistoric Cissbury Ring or at the windmill at High Salvington (both within my reach), I seemed to end up with my nose flattened against the window watching the raindrops run down like tears for another cancelled expedition. Mike wanted to go farming but there were no prospects for this in Britain without capital. Then came the Wembley International Exhibition in 1924. The Burma pavilion in carved teak was unforgettable and so was the Indian building, inspired by the Taj Mahal. But our thoughts were all on Australia. The Exhibition made us decide on Adelaide as the next base for our peripatetic family. It had flat roads for Dad, sunshine for Mum, agricultural college for Mike, a medical school for Felix and St Peter’s College for me. Though personally, aged 9, I was more interested in the vast vat of free orange juice at Wembley, perpetually being squished out of a limitless supply of oranges, and hoped there would be lots of such vats in Adelaide.

We sailed from Tilbury in December 1925 on SS Bendigo, an emigrant ship packed with twice its normal number of passengers because of the shipping strike, which had just ended. We spent Christmas at Las Palmas in the Canaries, calm after an especially stormy Bay of Biscay. My first view of Africa was through the porthole over Dad’s bunk before sunrise here magically was Table Mountain, painted in the palest of pinks and silvery greys. In the five days we spent unloading, Dad must have walked miles, arm in arm with Mike on one side and Fee on the other, as we explored the Cape peninsula by train and on foot. Mum must have been nearly dead from exhaustion, looking after three children and a disabled husband on an appallingly over-crowded ship.

Adelaide

In February 1926 we disembarked at Adelaide from SS Bendigo. It had been a six-week voyage from Tilbury.

At Adelaide’s outer harbour we had a rude shock. The immigration officer took one look at Dad, supported by Mike and Felix and said, “Who gave you permission to come to Australia?” I have no idea how that was answered, other than that my mother assured him, as a nurse, that Dad’s condition was not infectious.

The Medical School for Felix said he could attend lectures when we arrived in February but would not be allowed to register till his birthday – he would not be 16 until April 1926. Here is a summary of Felix’s professional life. He used to say he was probably the only medical student in the world who began his training not knowing how babies were made.

Jane and I, together with our son Christopher, his wife Nadine and daughter Olivia, and many friends and relations, celebrated Felix’s 90th birthday in Brisbane in 2000, where he had earned a CBE for his work as a paediatrician.

In Adelaide, Dad had trouble brushing flies off his face, either missing the fly entirely or giving himself a mighty whack on the cheek, but in other ways it was ideal. We bought a newly built house with what in England would have been thought of as a large garden. Dad revelled in planting every possible variety of grape over all its boundary fences and a dozen different fruit trees. Some of the peaches were so huge and delicate that you could hardly pick them without bruising them. The apricots cropped so abundantly that Mum had to take over the clothes-washing copper to make them into jam. There were nectarines and quinces fruits I had never heard of. When the grapes were ripe, I spent half my time filling my cycle-basket and taking them round to every friend we could think of.

I enjoyed Adelaide, not realising what a wonderful place it was to grow up in until after we left. Ten miles to the west was St Vincent’s Gulf, bordered by mangrove swamps north of the Outer Harbour, where the mail ships came in every Thursday and where the Sea Scout boats had their moorings. Six miles to the east were the Mount Lofty ranges, partly gum-tree scrub (Aussie for eucalyptus forest), partly fruit farms, with German-speaking villages dotted about where Australia’s wine industry began in the nineteenth century.

|

|---|

| Sailing the sea scout boat “White Star” in Adelaide Harbour |

|

|

Brother Scouts |

St Peter’s College – Adelaide

There were six years between my older brothers and me. I was a replacement for Dennis who died on his first birthday) so I was rather like an only child when I was young, with Mike and Fee away at boarding school or college. I went to school at St Peter’s College. As I was only ten I began in the Prep School. Father Julian Bickersteth the Headmaster was an important part of my life from 1926 – 33. My first memory was of Fr Julian coming down the drive from the Upper School to the prep school where he took VIa for Scripture. There was a craze at the time for flashing the sun into people’s eyes with bits of mirror. KJFB (our name for Bickersteth) must have been 50 yards away and I had only a small broken bit but I happened to get him fair and square.

He came into class furious. I was late into stowing my bit into my pocket and was told to get the cane. There was a slender, whippy one in the cupboard but also an old blunt one buried under papers. I managed to get the blunt one out. Just as I was getting two of the best, a boy came round with the mark-book, astonished to see someone being beaten by the Head. I can see him now standing open-mouthed. It was unknown for a boy in the prep to be beaten by the Head and he spread the news to each class as he went round. I became a person instead of being just a pommie. Shortened to Pom, that became my nickname all my time at Saints.

My parents felt there was a risk of my becoming “bookish” and fortunately pushed me into joining the school’s Scout Troop. I transferred to the Sea Scouts after about eighteen months and this became the joy of my life. They had a boat, The Pioneer, which had been the captain’s pinnace on the first warship ever to visit South Australia in the 1840s, so was then about 85 years old. Her bottom was filled with concrete and she was an open boat with no buoyancy tanks. If swamped, she would have gone to the bottom like a lead weight.

At the age of 16, I held a Charge Certificate entitling me to take the boat out into St. Vincent’s Gulf, which can get very rough, crewed by Sea Scouts without any adult on board or any of them wearing life-jackets! Our Sea Scout Master, Mikka Forbes, had served as an apprentice on square-rigged ships in the 1900s, in the days when sea shanties were still used as working songs. I used to produce them, in bowdlerised form, to lull our grand-daughters to sleep when they were small.

I never enjoyed ball-games and found cricket especially unappealing when the thermometer could go up to 113º in the shade so I took to rowing. The Torrens River was only a mile from the school, a pleasant bike-ride through the Botanic Park except for the time when a magpie stole the blue cap off my head. I began as a cox and took our house crew to victory.

On another occasion I was coxing a school four which was a good length behind our opponents in the last 50 yards of the race. To my horror I saw too late a stake in the water just ahead of number two’s oar. There was no time for evasive action and a moment later his oar hit the stake with a noise like a rifle crack. To my astonishment our opponents gave up rowing and cheered themselves. I suddenly realised that they thought the noise was the single revolver shot, which meant that the north side – their side – had won. And we were both 20 yards from the finishing line. I bellowed through the voice-trumpet “Row like bloody hell!!” They did and we won. I met Major Hill, our coach, in the changing room a little later. He had not seen the race and said to me, “Congratulations! I hear their fool of a cox hit a stake or something.” I said, “A bit like that sir.” Later I achieved the sole sporting success of my life, rowing bow oar in the Farrell House boat that won the house races of 1932.

The Senior Literary Society was a joy. There I first met the poetry of T.S. Eliot, introduced to me by Herb Piper, the only open atheist in the school, who went on to become Professor of English at Canberra. I also spent much time rehearsing with the Theatrical Society. Their greatest achievement was the Iphigenia in Aulis of Euripides, performed in the new Memorial Hall, which had almost insuperable acoustic problems. My part was that of Queen Clytemnestra, a role that Sybil Thorndike had played. She was then perhaps the best-known British actress of her time and was on tour in Adelaide. She attended our dress rehearsal and at one point leapt up on the stage with a copy of the book and started playing my part. I still have the copy with her signature in it.

Our Headmaster Julian Bickersteth had been an army chaplain, decorated for bravery in WWI, which also turned him into a pacifist. He formed the Bolshie Club – a group of boys thinking vaguely about ordination. We met for the office of Sext in a tiny chapel in his attic at lunchtime every Friday. On one occasion we visited the Community of the Ascension, a men’s religious order at Goulburn in New South Wales where we put on for them the Iphigenia we had just produced at school.

I had applied to the College of the Resurrection at Mirfield to train as a priest but since I could not attend an interview in England, it was arranged that Fr Barnes, who was visiting Adelaide and belonged to the Community, would see me then. The Head organised a picnic for the Bolshie Club and I had a few words with Fr Barnes but nothing that resembled an interview. When I reached Mirfield a year later, he greeted me like a long lost friend but said, “What on earth have you done with your hair? It was red and curly when I interviewed you in Adelaide.” I realised that he had interviewed Bob (Rufus) Ray, thinking he was me, but I was too far from home to be sent back. Bob later became my brother-in-law when Felix married his sister Dot.

After the Head, the most formative influence at school was Cammy, a one-time form-master of Scots origin, decorated in World War I, with an infinite capacity for resisting boredom. Friends and I used to drop in on him perhaps at nine o’clock at night and just talk, sometimes until midnight. He was never shocked, dropped in the occasional wry comment and almost never looked at his watch. It was only years later that we realised what we owed him.

Mike’s Dairy Farm and Possum

Our last four summer holidays were spent on Mike’s small mixed dairy farm, called The Snuggery. It was at the southern tip of mainland Australia, near the Victorian border and had been settled by Irish immigrants around 1870. The land was originally a tea-tree swamp, so dense, the old people said, that a dog couldn’t walk through it. All the farms in the area had been started by old man McCourt who had eleven sons and one daughter, Julia. She lived, as her parents had lived in Connemara, in a tiny cabin with the pig in the end room.

Old man McCourt used to sit with a telescope on the chimney stack while his eleven sons were sent out, each to clear his own patch of tea-tree, while he kept watch to see that they were all working. By the time Mike arrived in 1929, all except two had drunk themselves off their farms. The two were the local butcher and Jim on the next farm. Jim had only one leg that worked and travelled in a light dray with a hole in it for the leg was too arthritic to be bent. He had not got round to building a milking-shed in the 50 years he had been farming and used to milk his cows with the daily rain pouring down his neck. At The Snuggery, it took Mike a full day to clear the mountain of whisky bottles in his yard.

Possum, Mike’s black pony at The Snuggery, was the love of my life. He only had one vice. He could not resist thistles and at full gallop would suddenly stop to nip off a tasty one in full flower. He had never been broken in and had never heard of trotting and cantering. He had only two paces, a walk and a gallop. Mike had inherited him from Jack McCourt who used to ride him six miles at full gallop to the “Tantanoola Tiger.” (Google Map). There he would get drunk and relied on Possum to bring him home. Often Possum arrived back alone.

|

|---|

|

Back: Mike, Stanley, Felix, Winifred front: Zetta, Donald |

In 1934, soon after I left school, Mike’s lovely wife Zetta died in giving birth to Rosemary and I rushed down to be with him. He was learning the hard lessons of being a dairy-farmer. If your wife dies in the morning, the cows still have to be milked in the evening. We had a wonderful couple of months together. One of my jobs was to get the cows in. At half-past four in the morning you first had to catch Possum who was loose in the paddock. That was a game he loved. I could trot around for a quarter of an hour before he condescended to accept the bridle.

It was he who rounded up the cows – I was still half asleep. If they were a bit sluggish, he would just bare his lips and nip their bottoms. The more spirited cows would land him one under the jaw with their back hoof. He would stop in his tracks and I had to avoid shooting over his head. I never actually came off him and I usually rode bare-back to get an extra five minutes sleep. I loved Possum dearly. He was a shiny jet black in the summer and in winter a dark woolly brown. At 8 in the evening we started cooking – after separating the cream and feeding the calves – usually an all-purpose soup stew that changed slightly from day to day, followed by riz-au-chocolat.

Following Zetta’s tragic death my parents offered to look after baby Rosemary for which Mike was very grateful. After I arrived in England they decided to return to England and Worthing, together with Rosemary.

–End–