I came back to Malawi at the beginning of August from leading a retreat for clergy in Southern Rhodesia to find the government was torn in half by disagreements between Banda and his cabinet. The three most powerful ministers were Henry Chipembere, then away in Canada and the only Anglican, Orton Chirwa, who had sponsored my appointment, and Kanyama Chiume.

There were three main reasons why the ministers were rebelling.

- The rebel ministers wanted strong links with mainland China, whilst Banda insisted on developing relations with Taiwan.

- In addition they objected to Banda’s friendly relations with Apartheid South Africa and Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique)

- They were also not happy with the slow pace of Africanisation of the civil service and other issues.

In Henry’s absence they presented Banda with a list of issues on which they disagreed with him. They were also frustrated with Banda’s reliance on Cecilia Kadzamira and the Tembo family, and riled by his repeated reference to them in public speeches as “my children”.

Treatment of dissident ministers

After a week of discussions, often positive, Banda turned them out of his office saying, so that everyone could hear, “You will not make a Nyerere out of me. You can shoot me. I will not be Nyererized.” – the reference being of course to the gentle and unassuming Julius Nyerere of Tanzania.

Orton was beaten up several times by Banda’s supporters after he met with Banda. The Governor General Sir Glyn Jones subsequently wrote to Orton to say that Banda had agreed only to an acting appointment as a judge, provided he first made a public declaration of loyalty to him and his political disassociation from the other ministers. But Orton had had enough. He left Malawi for Zambia, hidden in the engine-room of a boat from Fort Johnston to Nkhata Bay, and then on to Tanzania. He was the last of the ministers to leave Malawi, all the others, except Chipembere, were already in Tanzania or Zambia.

Henry Chipembere had been the closest to Banda, as he was the only minister to have shared fourteen months in prison with him at Gwelo, in Southern Rhodesia. Much of the detailed planning for the independent Malawi was done between them. He was also the last to be set free in Nyasaland. Sir Robert Armitage, the previous Governor, had prosecuted him for incitement to violence, for which he was sentenced to three years in Zomba prison. I visited him there – something which Banda never did – and we became friends.

Henry came back from Canada on the 8th September and addressed public meetings in Fort Johnston (Mangochi), Blantyre and elsewhere supporting the rebel ministers. Banda banned all public meetings without police permission and issued orders to the police, “If necessary people must be shot and I mean that the Police must shoot to kill.” On the same day a meeting in Soche addressed by Henry was broken up by gangs of pro-Banda Malawi Youth.

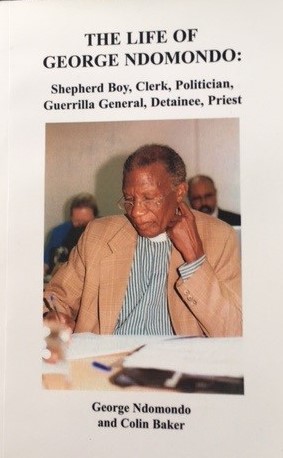

Two days later there was a general strike of all African civil servants in Zomba. On 30th September 1964 Henry was issued with an order confining him to a four-mile radius of his house in Malindi. Henry saw this as an opportunity to form his own ‘army’ of over 400 men in the uninhabited forest area which they called ‘Zambia’, between the lakeshore and the Mozambique border. The army was in sections commanded by ‘generals’, one of whom was George Ndomondo, whom I ordained a priest in 1975 and he is still doing Yao translation work. His eventful life is described in The Life of George Ndomondo. (George died in 2015)

Copies of this book can be requested from the Secretary of MACS http://malawimacs.org/

Armed rebellion

The staff at our lakeshore centres were well aware of what was going on and kept me informed. At about 9.00pm on 12th February 1965, Henry and some 200 hundred men headed for Fort Johnston. Here they attacked the police station and made away with the guns belonging to the police. While this was going on, the District Commissioner, who had been spending the evening with one of our missionary nurses, was greeted by a hail of bullets as he returned to his house. Without stopping to gather details, he drove the forty miles to the Malawi Railways dockyard at Monkey Bay to send a wireless message – telephone lines having been cut – to the army and police headquarters, to tell them of the armed attack.

Henry and his now better armed men, headed 60 miles south for Zomba, the capital. This involved crossing the Shire River at Liwonde on the ferry powered by a diesel engine. The ferry was on their side of the 75m wide and fast flowing river but, unhappily for them, the engine had broken down. Despite energetic exhortations to the mechanic, the engine remained silent. When, after some hours, the army began to arrive on the other side of the river, Henry had no option but to retreat with his men to the wild no-man’s land north of Malindi. Here he remained with an ‘army’ of three to four hundred men, where the Malawi Army could neither find them nor defeat them.

In March 1965 Henry wrote to Banda through the Governor General, Sir Glyn Jones:

“On grounds of principle I will not leave the country. That would be an act of desertion or betrayal of our supporters in gaol… If I did not have support I would be in my grave now. But the villagers themselves hide me, feed me and stand guard around the village to warn me.”

He asked Glyn Jones to mediate and seek an amnesty for his men who were ‘languishing in gaol, exile and the forest’. Banda’s response was to make the death sentence mandatory, and to abolish the constitutional right of appeal to the British Privy Council. The results were described by Henry in another letter back to Glyn Jones:

“The security forces are perpetrating unheard of brutalities… Rape, burning of houses, shooting, beating of men, women and children, looting of homes, stores and gardens, indiscriminate arrests etc. are the order of the day.”

Colin Baker, to whose Revolt of the Ministers I am indebted for much detail previously unknown, adds:

“It could have been worse. When the Commander of the Malawi Army was instructed to carry out the campaign, he told his officers to take a drum corps with them and make plenty of noise to warn the inhabitants of their imminent arrival and give them a chance to escape.”

Diabetes did what Banda was unable to do. In the bush, Henry received medication for his diabetes from various friends but was unable to cope with this long-standing problem. Chiume says he was almost dying of diabetes. With Banda’s full consent he was smuggled to America via London. I was able to play a part in making this possible. I met him some years later in Los Angeles, where he died in 1975.

Chipemberes sail to Likoma for safety

I had hardly been at home and had seen little of Basil since he was born in April 1964. We had to cancel our holiday, so in October Jane and I and six-month old Basil were spending a few nights on nearby Zomba mountain. We took with us the few architects’ plans that we could lay hands on. There was not an architect left in the country, apart from those in the Public Works Department, and for the first time there was a little money for the clergy houses, health centres and schools that were so desperately needed. This space would enable us to sketch out plans for buildings that could be afforded.

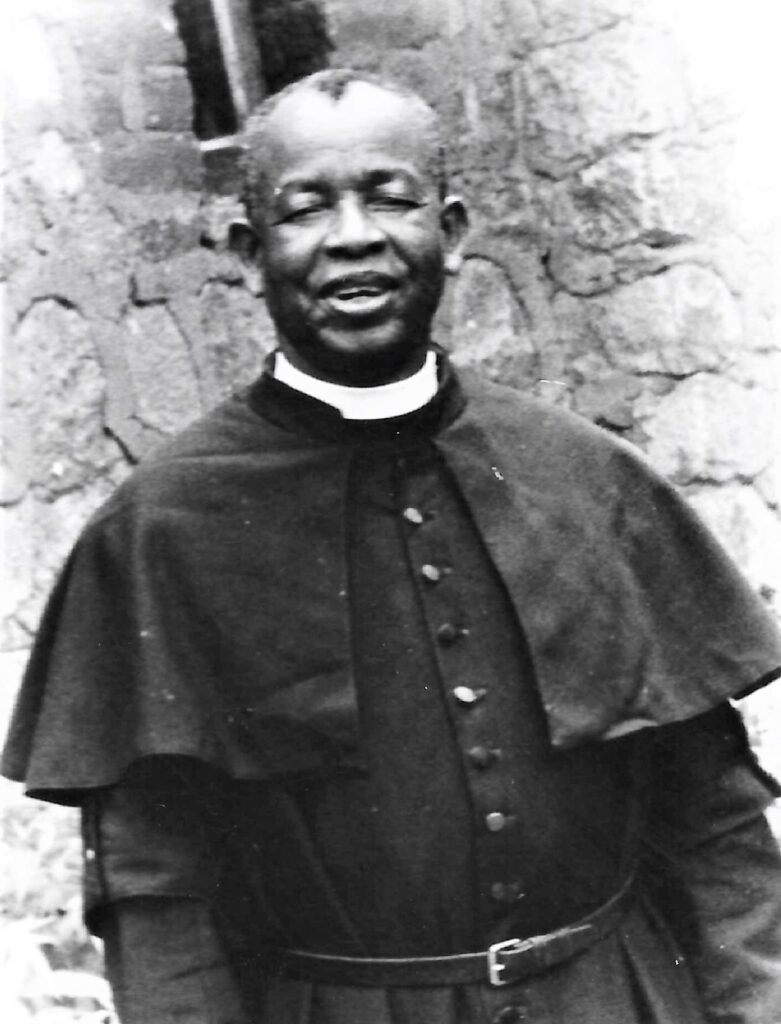

In the small hours of Saturday morning there was a telephone call from Sir Glyn Jones, the Governor General. President Banda and he were both worried about the safety of Catherine, Henry Chipembere’s wife, her children and of his father Habil, the Archdeacon of South Nyasa. Would I go at once to Mponda’s, where Habil was now living and persuade him to go to Likoma Island, and then to Malindi to persuade Catherine to go with him. A large Fisheries boat was on standby at Mponda’s and John Bolt the District Commissioner would accompany them to Likoma.

We drove down the mountain, left baby Basil with the Croftons and headed for Mponda’s, 75 miles away. Habil and his wife listened to the message and, with obvious sadness, agreed. But how could their daughter-in-law Catherine be persuaded? She was in hiding near Malindi, ten miles north-east on the other side of the Lake. We agreed that I would stay with Habil and sail on the government Fisheries boat with them to Malindi to pick up Catherine and the children. Jane would go by car and take on the harder task of persuading her to go, knowing that she might never see her husband Henry again. He was officially a bandit, having broken the rules of his confinement to Malindi, and the army was out searching for him.

On arrival at Malindi mission, Jane was told to drive four miles north to the village where Henry and Catherine had their house. There she was asked to leave the car and walk some distance to the house and wait. People were polite but suspicious. Eventually Catherine, looking rather dishevelled, emerged from the bush and sat and listened to Jane’s message and, after many reassurances, agreed to go to Likoma. She went off into the bush again to gather her three young children and a few belongings. After some time, she returned and walked with Jane to the car. By this time a threatening crowd of several hundred people had gathered. The spokesman for the group, John Liomba, said they did not trust what was happening but Catherine was able to persuade them that she wanted to go. Jane then drove Catherine and the children to the mission on the lakeshore at Malindi. Several years later John was ordained as a voluntary priest.

Henry and Catherine Chipembere in happier times

When the Fisheries boat reached Malindi, I was served with an ultimatum. Either Archdeacon Habil came ashore or I would never see Jane again. Habil parried this threat – he was highly respected, both as a much-loved Archdeacon and as an active representative of the Malawi Congress Party.

It was dark by the time Catherine and Jane arrived at Malindi, from where it was just possible to see the silhouette of the Fisheries boat with only her guiding light showing. It took several trips in a small dinghy to ferry Catherine, her children, belongings and Jane out to the boat. Jane asked Catherine if there was anything she wanted. She thought for a moment and then said, “Shoes for the children.” Jane found some paper and, as the boat rose and fell in the swell, drew outlines of the children’s feet so as to know the sizes.

After giving God’s blessing to Habil, his wife, Catherine and the children, we boarded the dinghy and watched the lights of the Fisheries boat disappear into the distance. Apart from a brief meeting in Zambia some years later, it was the last I saw of Habil, who I had once thought would be the first African bishop in Malawi. He had been ordained before World War II, in which he was an army chaplain and served in India. At the UMCA centenary in London in 1957 he had been presented to the Queen and made a five minute speech of thanks for those who had brought the gospel to Nyasland.

It was now 10.00 pm and, after a bite of food with Francis Bell, the wonderful mission engineer based at Malindi, we headed back the 85 miles to Zomba. A few miles down the road, we were surprised to see a fire ahead and realised that the bridge over the Lusalumwe river was burning. A small group of people watching it said the bridge had been set on fire to prevent us leaving Malindi. They were still uncertain as to whether the Fisheries boat was a trap to capture Catherine and her children.

We returned to Malindi. The never-at-a-loss Francis showed us a small, little-used track running close to the lakeshore that would bypass the fire. We started off again. Before reaching Mangochi, we were surprised to see the lights of a vehicle heading towards us. This was the police who had been instructed by their HQ in Zomba to find out what had happened to us. We eventually fell into bed in Zomba at 3.30a.m.

The Church’s role

In April 1965, Habil Chipemebere wrote to me to say that, owing to inflammatory speeches by visitors to Likoma, Catherine and he no longer felt safe. After months of discussion, Banda agreed to transport them with an escort of Young Pioneers to Mbamba Bay in Tanzania, but only on condition that he leave Malawi for ever. Habil was profoundly distressed because his three daughters were all married to Malawians, he ended his letter, “If I cannot return back to this country then I shall bow my head with tears under the Prime Minister’s feet and obey his orders.” I saw Habil only once more, in Zambia – a dear and much respected friend who had married Jane and me and baptised Basil. He died some years later in Tanzania.

For the next decade, Malindi – the most important and, almost the oldest mainland Anglican centre – was under a heavy political cloud. This resulted in the internment of many leading Anglican laymen and the closure of the 70 year-old St Michael’s Teacher Training College.

It was some time before the full impact of the Banda-Chipembere conflict was felt. From now on Banda was the undisputed ruler. The Young Pioneers became a quasi-army, not the spearhead of modern agriculture, trained by Israelis, as they were first presented to the country. Ministers were hired and fired according to whim.

The Churches did what they could to restrain the more evil aspects of policies that often appeared progressive to outside observers, who praised Malawi as an island of peace compared with the Congo, Mozambique and South Africa. There was truth in this but the price of living in a police state was high. Many Malawians were incarcerated under appalling conditions of solitary confinement, some for eight years and more. Expatriates were declared to be prohibited immigrants, and ‘P.Id’ with twenty-four hours to leave the country, including one of our missionaries.

The heads of Churches met informally, sometimes in our house, to exchange information and, to bring to bear, what pressure we could. Often this was done through Blantyre Synod and its General Secretary Jonathan Sangaya since most of the ministers belonged to the CCAP. Victor Smith, a wise senior missionary of the Churches of Christ, which in England is part of the United Reformed Church, was our secretary and was once asked to convey our feelings to Banda. Once, when Victor Smith accompanied Jonathan to his meeting with Banda, the meeting was interrupted by the Secretary of the Malawi Congress party bringing a list of people to be detained for Banda to sign. Banda agreed to all the names except one. “We want them all.” “No, not that one.” “We want them all.” “Oh, very well.” After the MCP Secretary had left, Banda turned to them and said, “Some people think it’s easy to be a President.”

Trying to reinstate the Scouts and Guides

Soon after independence President Banda banned Scouts and Guides. The reason for this banning was the serious mistake made a few years earlier when the then Commissioner, Dorothy Peterkins, withdrew the warrant of a promising Malawian guider, Grace Rubadiri, for taking part in political rallies.

Jane, who had been running a Guide Company and a Sea Ranger Crew for a number of years, succeeded her as Commissioner. She and the Deputy Commissioner, Jean Potter, were granted an interview with President Banda to make the case for lifting the ban. The President appeared sympathetic but, despite the support of the Government Minister, Aleke Banda, who was a keen Scout, they were subsequently told that the ban would remain.

Postscript

Catherine returned to Malawi when Banda’s rule came to an end in 1994 and was elected MP for Mangochi East, where her husband Henry had been the first MP. She married Clement Marama, our lay representative to the 1963 Toronto Conference – they retired to live on Likoma island.

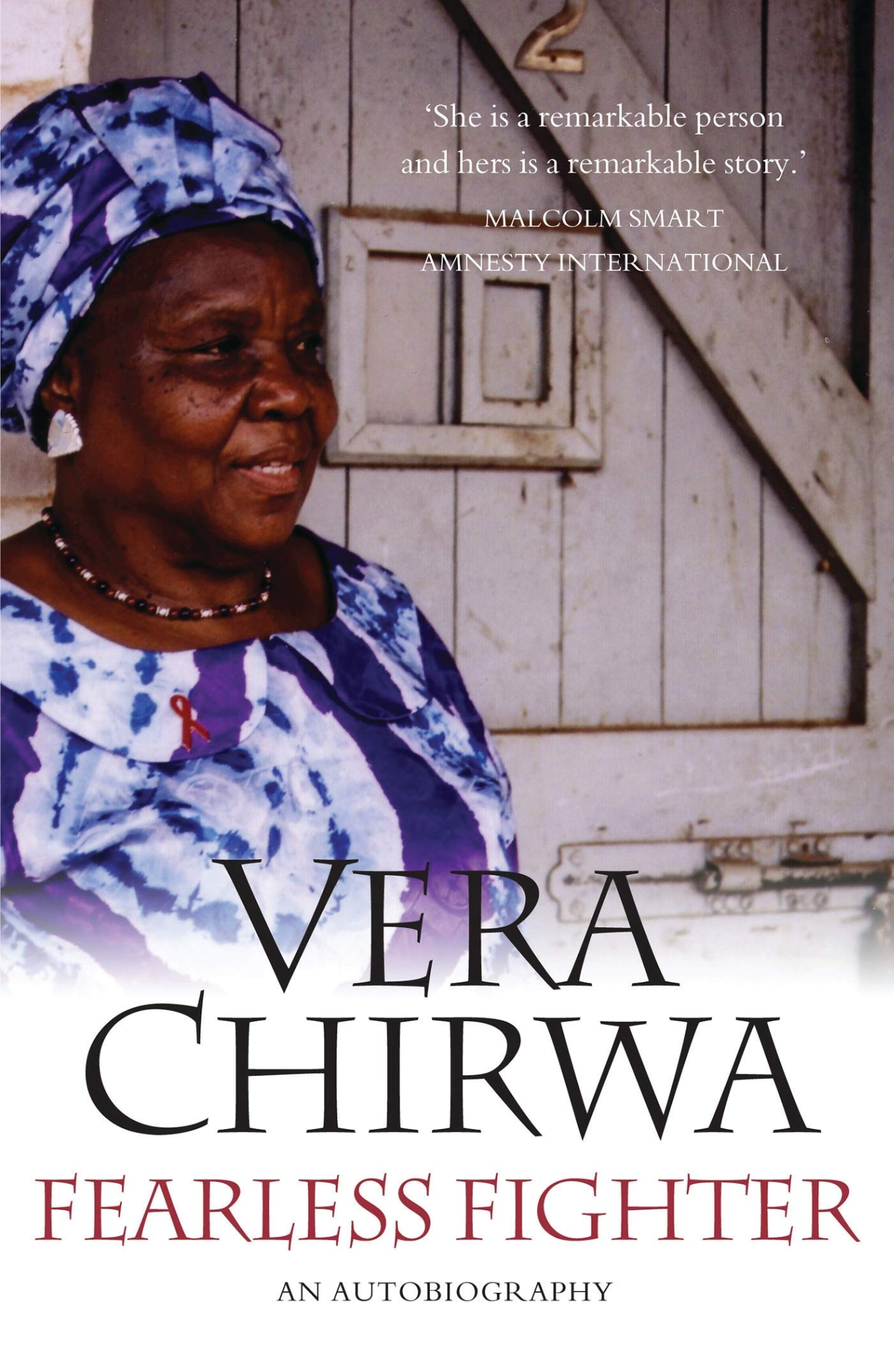

In 1981, Orton, who was teaching law in a Zambian university, and Vera Chirwa unwisely decided to revisit Malawi. At the Chipata border, they were arrested by Malawi police and then held separately in Zomba prison, manacled to iron bars for long periods. Their son, Fumbasi, was detained incommunicado without charge for over two years. Orton and Vera were tried before a Traditional Court on charges of treason in May 1983. They were not permitted to call witnesses for a defence and were both sentenced to death. In response to an international outcry, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Although both were in Zomba prison, they were not allowed to see each other until September 1992, when a delegation of British lawyers was given access to them. Orton, ‘nearly deaf and almost blind from untreated cataracts, and often in leg irons’ died the next month. Vera was not allowed out of prison to attend his funeral.

By this time Vera was ‘the longest serving African prisoner known to Amnesty International’. She was released from gaol three months later. She has spent the rest of her life fighting for women’s rights in Malawi. The autobiography of this brave and amazing lady entitled Vera Chirwa: Fearless Fighter was published by Amnesty International in 2007.

If it had not been for Orton’s speaking up for me, I probably should not have been allowed to enter Malawi – certainly not to function as a bishop after independence.